FEMA, HHS turn to ‘social listening’ for better disaster response

Emergency management agencies say existing social media channels are often their best way to crowdsource and collect important information during a major weather...

Emergency management agencies are beginning to realize the best information they can gather during an emergency or natural disaster doesn’t come from their own government-built apps.

It comes from existing social media channels.

“That technology is not new,” Geoff DeLizzio, CEO at the American Red Cross national capital region, said at AFCEA Bethesda’s monthly breakfast series March 24. “That technology is not necessarily innovative. [It’s more about] how we’re using it and making management decisions to say, ‘Just go, go do it, we hear something here, let’s make that happen.’ Disasters are messy and we have to act quick.”

FEMA, for example, launched its own Disaster Reporter App last year. The app was designed to give users more information and collects user-submitted photos from the scene of a natural disaster or major weather event.

“Unfortunately, we’ve been underwhelmed with the use of that app, because I think everyone is at the Weather Channel doing their Instagrams there,” said Scott Shoup, chief data officer at FEMA. “Instead of trying to do everything ourselves, we need to find smarter ways to integrate the social media world more effectively into how we perform our business functions.”

Shoup said some of the best social media intel he ever saw was a series of tweets from high school students driving around their neighborhoods in New Jersey during Hurricane Sandy.

“We looked at it with fascination at FEMA’s [National Response Coordination Center],” he said. “‘We were like, ‘Wow, this is the best intel we have.’ I don’t know to what extent we used it for operational decision making because of the validity question, but that’s the piece we have to harness, is coming up with that validity. Great, we can have it in our FEMA app, but we have to come to the reality that that’s going to be 2 percent or 5 percent of what we’re going to get.”

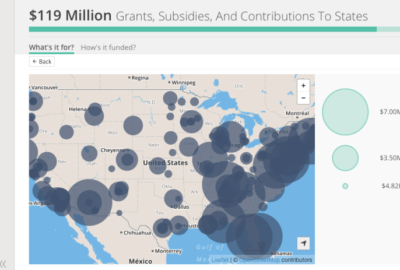

In the past, agencies like FEMA would create an action plan for a specific disaster after it collected data from local and state organizations, or it would send emergency response teams specifically to the scene to gather more information. But those strategies take too much time, Shoup said.

Now, FEMA and the Red Cross are monitoring social media outlets, collating information in real time and using it to act immediately.

“We will see on a street three people talk about water being out, and within 20-30 minutes we can have water on their street,” DeLizzio said.

The Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Emergency Management uses social media in a similar way. During the Martin Luther King Day March on Washington in 2013, HHS learned through social media that several people were suffering from heat exhaustion, said Nancy Nurthen, fusion division director at the agency.

HHS sent mobile clinics teams to the Washington Mall soon after it read about the complaints online.

“For a lot of the tools we use, the platforms weren’t developed for the way we use them, but the analysts can develop a methodology to pull out information that’s very actionable, very timely [and] very useful,” she said.

Nurthen said her agency is learning to become “social listeners.” Data analysts search social media outlets to gather relevant information and public affairs officers use that data to spread it to the public.

Cora Russell, acting director of the Office of Emergency Management at the Food and Nutrition Service, said her office will soon meet with social listening specialists at FEMA to learn how they can better implement those strategies.

For FEMA, “social listening” also means working with the public affairs office to dispel rumors or correct information that might not be accurate or may have already been addressed.

“It’s all just noise coming in,” Shoup said. “Something that was tweeted 15 minutes ago may already not be the case. A road that has a tree down may have already been moved.”

It also means FEMA is beginning to change the way it designs new data processing tools and how it conducts business with industry. That kind of cultural shift is often harder to swallow, Shoup said.

“We look at that specific outcome and we work backwards,” he said. “We work backwards through decision making, analytics, data and then finally the system, instead of building the system first. What you just described was not a $400 million government system, was it? It’s just Twitter.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED