Stars aligned for civil service reform in 1978; will they again in 2018?

As the Trump administration considers civil service modernization, those who helped craft the original Civil Service Reform Act say the White House could do the...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

When it comes to the ambiguous topic of “civil service reform,” 2018, in a sense, looks a lot like 1978.

Still reeling from the Watergate scandal, 33 percent of Americans said they had trust their government would do what’s right most of the time, according to data compiled by the Pew Research Center. Today, Pew research clocks the public’s trust in their government at 18 percent.

President Jimmy Carter in his 1978 State of the Union promised his administration would restore merit principles, give federal managers more flexibility and provide “better rewards for better performance.”

The system, Carter said, has grown “into a bureaucratic maze.”

President Donald Trump, in his State of the Union 40 years later, called on Congress to help cabinet agencies “reward good workers and remove federal employees who undermine the public trust or fail the American people.”

In 1978, long-time federal leaders and experts bemoaned the federal personnel system as one that gave career managers little incentive and room to move up.

“Attitude surveys of federal managers at that time indicated they were as disillusioned about how well the system worked as was the general public,” Alan Campbell, who served as the first OPM director and a former chairman of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, told the Senate Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on Federal Services, Post Office and Civil Service back in 1988. “They did not believe they could manage the system; they believed that the oversight agencies imposed restrictions and regulations that made it impossible for them to be effective.”

Today, federal managers have described a similar state of affairs in a letter to House Oversight and Government Reform Committee leadership.

Civil Service Reform Act 40 years later

Now nearly 40 years after the passage of Carter’s major civil service changes, the Trump administration is attempting a similar feat. This time, as Federal News Radio explores in part one of its special report, Civil Service Reimagined: 40 Years Later, overcoming the barriers to success may be an even higher wall to climb.

Citing an “incomprehensible and unmanageable civil service system,” the Trump administration released its own reorganization proposals and touted a new agenda for the federal workforce that will prioritize performance-based pay and rewards, faster accountability and removal procedures and more efficient collective bargaining.

But it’s unclear whether the Trump administration’s attempt at civil service modernization will come in the form of new legislation as comprehensive as the Civil Service Reform Act or simply a series of new bills and executive or agency actions.

So far, the White House has relied on three executive orders as an attempt to implement some of the more impactful changes to the federal workforce.

The Office of Personnel Management has promised it would be busy this year pushing out new executive actions and legislative proposals. The agency has recommended comprehensive changes to the current federal employee retirement system, but Congress hasn’t acted on those proposals yet.

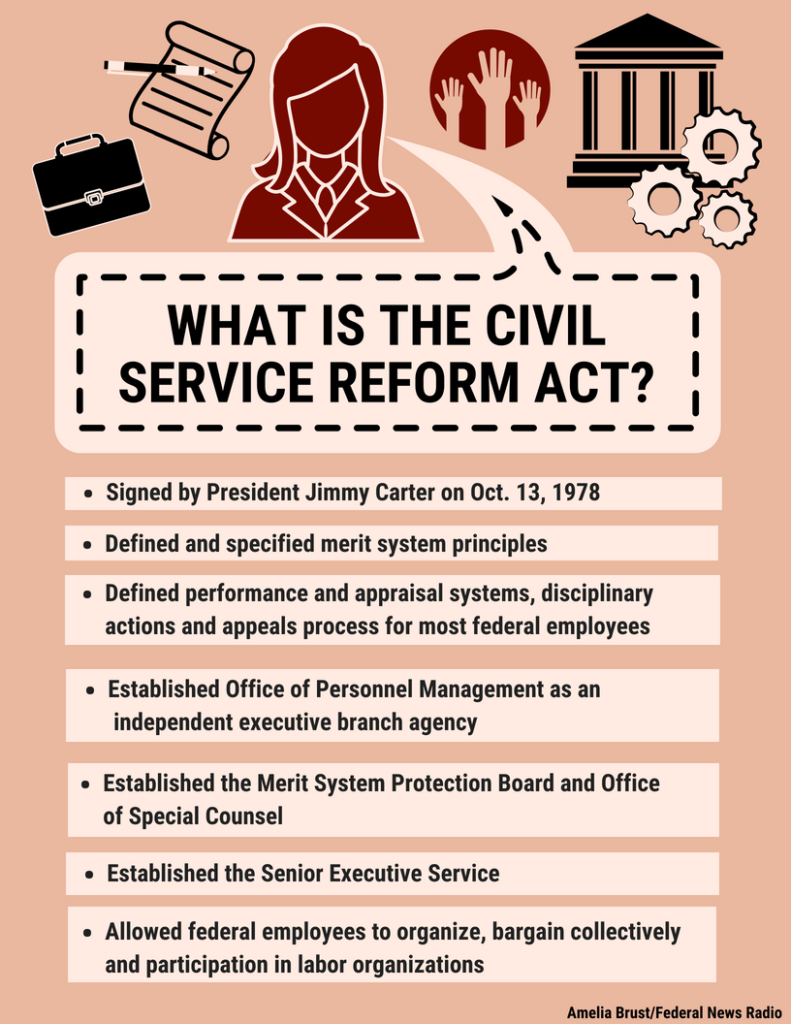

By all means, Carter’s legislation in 1978 was sweeping and comprehensive. It created several agencies, including the Office of Personnel Management. It established the Senior Executive Service, codified federal labor relations as statute and set whistleblower protections.

“I don’t know of any instance in which one of the major governmental system [reforms] was as comprehensive as what we were proposing,” Dwight Ink, a long-time federal manager and executive, said in an interview with Federal News Radio. “Because it was comprehensive, we were able to describe it in a such a way that resonated with the public. If we attempted something much smaller, we would not have been able to appeal to the public.”

Ink is widely seen as one of the leading voices behind the Carter administration’s civil service initiative. He and the Carter administration viewed the Civil Service Reform Act as simply the start of a long, complex and dynamic conversation about the federal workforce and government should manage it.

But is the Trump administration prepared — and willing — to begin collaborative discussions and the complex task of parsing through a civil service system that largely hasn’t been updated in 40 years?

It takes a level of detail and devotion — and the right people — to carry such comprehensive change forward, Ink said.

“Today, if you have that kind of leadership, you could do just what we did,” he said.

From draft to law in seven months

Those who played a key role in the legislation’s passage in 1978 say, to this day, drafting and developing the Civil Service Reform Act was a special act of government.

The law became a reality because the White House — and Carter himself — paid special attention to the topic and developed a particular understanding of the career civil service, Ink said.

Carter’s interest in the civil service started during the aftermath of Watergate and on the campaign trail, where he and his advisers discussed a wide range of good government and ethics reform ideas, said Stuart Eizenstat, who worked with the president on the campaign trail and eventually became his chief domestic policy adviser. He helped the president through civil service reform and other good government legislation, as Eizenstat described in his recent book “President Carter: The White House Years.”

“His view of the permanent civil service was that they needed to have more flexibility, more incentives, more encouragement [and] that there was a lot of dead wood,” Eizenstat said in an interview. “But he also respected the collective bargaining units.”

To kick off the initiative, Carter created the President’s Personnel Management Project when he first took office in 1977. He appointed Ink to serve as the project’s executive director and Campbell, the well-regarded chairman of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, to help lead the administration’s efforts.

The project consisted of nine task forces and several advisory groups, which developed a problem analysis report with more than 100 recommendations. Ink said the Carter White House engaged the public and held town hall meetings with employees to develop those recommendations.

Carter ultimately left it up to his task forces to sort through the details, but he approached the civil service with “depth,” Ink said.

[The president] “was very much involved in the selling of it and [talking] about it to the public and to the Congress,” he said.

Those messages to the public started in earnest in 1978, when Carter, in his State of the Union that year, declared civil service reform as “absolutely vital.”

President Jimmy Carter in his 1978 State of the Union promised his administration would restore merit principles, give federal managers more flexibility and provide “better rewards for better performance.” In its special report, Civil Service Reimagined: 40 Years Later, Federal News Radio looks back at the legislation’s passage and how it’s faring four decades later.

Posted by Federal News Radio on Monday, August 13, 2018

In March, Carter presented a reorganization plan to Congress, which eliminated the Civil Service Commission and replaced it with the Office of Personnel Management, the Merit Systems Protection Board, Office of Special Counsel and Federal Labor Relations Authority.

Legislation outlining actual civil service changes came later. Drafting, lobbying and passing both the reorganization and the civil service provisions took seven months, Eizenstat said.

Carter’s attention to detail, in this case, proved to be helpful, Eizenstat said, but Campbell’s leadership and knowledge of the civil service system was invaluable.

“Campbell kept myself and the president informed at each stage to make sure that the legislation that was going to come out was going to be one he could sign,” Eizenstat said. “He also gave the president a list of congressmen and senators to call when we had tough votes coming up in committee on things like whistleblowers and the Senior Executive Service. And he did.”

The White House also held weekly meetings with Democratic leadership and monthly meetings with Republican members to discuss the legislation, Eizenstat said. Carter also “reached out very deeply” into the civil service itself to find out what was important to federal employees.

The conversations were largely apolitical and bipartisan, Ink said, a feat that seems practically improbable today.

There were controversial conversations, Eizenstat said. The creation of the SES sparked heated debate over pay. Discussions over federal collective bargaining units were often contentious, as they are today.

“We sort of rode a crest over those bumps because of the whole post-Watergate feeling that we needed to shake up the system, protect employees, create incentives for top managers and have whistleblower protection so that if there were the kinds of abuses that occurred in the Nixon era, whistleblowers could be protected and not [be] fearful of losing their jobs,” he said.

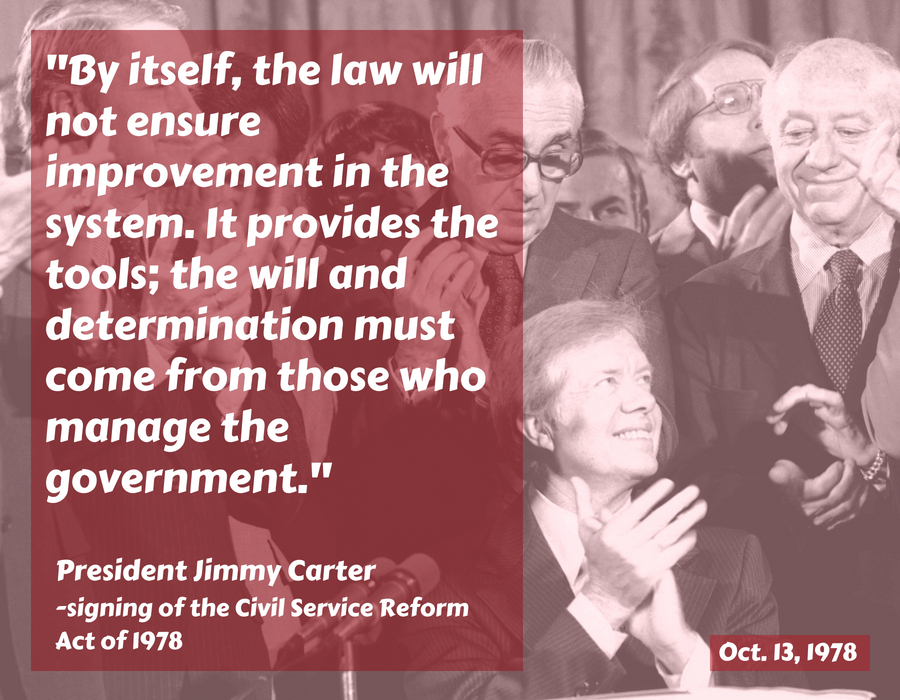

In October 1978, the legislation reached its final step. It passed the House with a 365-8 vote. Carter signed the Civil Service Reform Act into law on Oct. 13, 1978.

But the White House never intended conversations about the civil service to end on that day in October.

“This is just the start of a continuing effort to improve the federal government’s services to the people,” Carter said during the Oct. 13 signing ceremony. “By itself, the law will not ensure improvement in the system. It provides the tools; the will and determination must come from those who manage the government.”

It requires ‘constant nurturing’

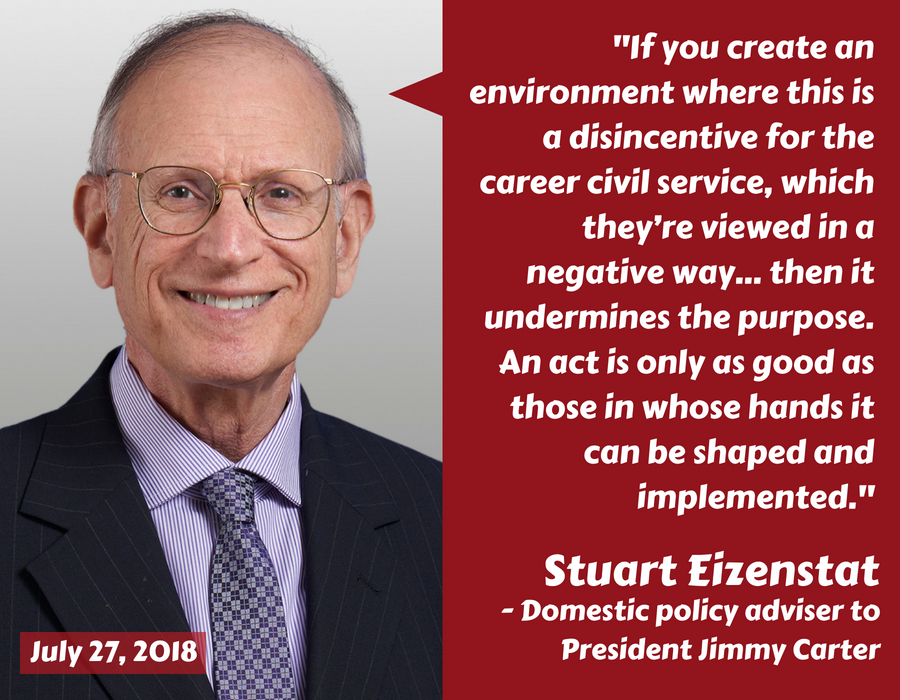

Today, Eizenstat acknowledges the Civil Service Reform Act has its detractors. But he said the law defined and championed merit principles, which have stood the test of time.

The civil service law was never intended to be completely static and left to its own devices, he added. Rather, the civil service system —and the Office of Personnel Management, Merit Systems Protection Board and Federal Labor Relations Authority — need consistent attention and care.

“We also recognized that in order to have it fulfill all of the hopes and dreams that we had … it requires constant nurturing,” Eizenstat said. “It requires a president and an administration that values the civil service system — that wants to enhance it, that wants to improve it, that wants to incentivize and not politicize it. They require nurturing by the White House, by the president and by the leadership. If you create an environment where this is a disincentive for the career civil service, [where] they’re viewed in a negative way, then it undermines the purpose. An act is only as good as those in whose hands it can be shaped and implemented.”

Did subsequent administrations and federal managers use the Civil Service Reform Act to shape and evolve with the times? In part two of Federal News Radio’s special report, Civil Service Reimagined: 40 Years Later, learn how the federal workforce has evolved over the past 40 years, despite a civil service system that’s remained relatively static.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED