The Senior Executive Service remains less diverse than the federal workforce overall

Over time, the SES has grown in numbers and become more diverse along the way, but it’s still not fully representative of the federal workforce, the Partnership...

As you look higher up in the ranks of the federal workforce, you’ll find less diversity among some of the government’s senior-most leaders.

That lack of diversity in the Senior Executive Service — the cohort of federal senior leaders serving just under agencies’ top political appointees — has been evident for decades. Notably, though, it has improved in just the past few years.

Over time, the SES has grown in numbers and become more diverse along the way, but it’s still not fully representative of the federal workforce’s overall demographics, the Partnership for Public Service said in a report published Tuesday.

“As public servants, a primary responsibility is being a steward of the public good,” Max Stier, the Partnership’s president and CEO, told Federal News Network. “Having a government made up of a broad swath of our population is more representative of the people. Diversity across the board is something that improves performance, improves the public’s perception of public service, and more broadly, it’s something that you should be keeping an eye on, which is part of the reason why we’ve done this report.”

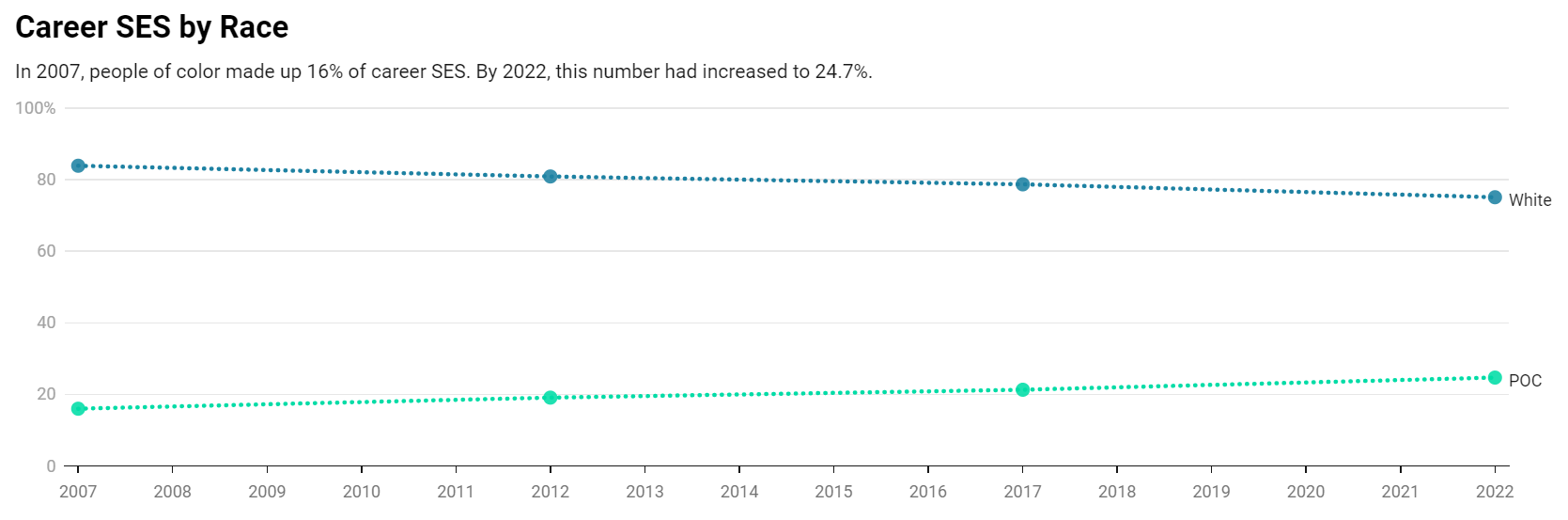

Currently, people of color represent 24.7% of the career SES workforce. It’s a slow-moving but significant step up from the 16% of SES members in 2007 who were people of color.

But that increase looks smaller compared with the federal workforce overall, where 39.2% of feds identified as people of color in 2022.

The Partnership’s data, which spans a quarter-century, also showed that the percentage of women career SES members increased from 20.1% to 37.6% between 1998 and 2022. But again, the percentage still lags behind the 44% women who make up the federal workforce overall.

The report’s trends mirror recent data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which similarly showed that higher federal workforce diversity is more concentrated in the lower levels of the General Schedule.

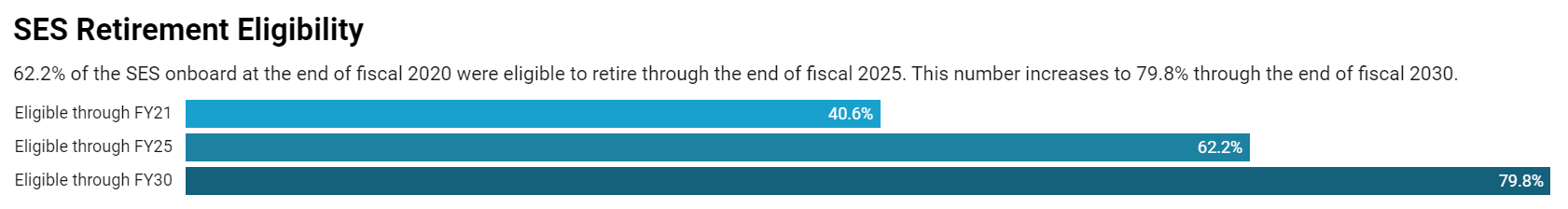

The Partnership found that the SES also consistently struggles with a limited age range of those who hold the senior-level positions. For decades, feds in their 50s have made up the majority of the SES. Just over a quarter of SES members are above age 60, but more each year are starting to reach retirement age, with fewer younger feds to fill in behind them.

The number of those leaving the SES is increasing, too, in large part simply due to retirement. At the end of fiscal 2020, 40.6% of SES members were eligible to retire within a year. But 79.8% will be retirement-eligible by the end of 2030, according to the Partnership’s report.

At the same time, there are about 200 new hires coming into career SES positions every fiscal year. The hires come from a combination of those moving up in the ranks of federal service, as well as those coming in from the private sector.

While there have been ups and downs with the exact number of new hires each year, the number of newly hired SES members has flatlined in just the past couple years.

“200 hires, on average, a year is not very many,” Stier said. “But having an inflow of talent from the outside improves diversity. One of the things that I would highlight here is, frankly, how few folks from the outside actually come into those senior positions.”

But that SES hiring needs to happen in the right fields, too. The IT workforce has seen the largest year-over-year growth in SES members, going from 0.5% of the overall SES, to 3.4%, in the last two decades. That’s an increase of 542.6%. But for Stier, the increase hasn’t gone far enough.

“I’m not sure that we’ve seen the extent of reshaping of the occupational focus as we should have,” Stier said. “To be an effective leader in today’s world, having that technology sophistication, I think is fundamental.”

And although 80% of the federal workforce lives and works outside the national capital region, SES members more often tend to work in the area. For the last 25 years, 7 in 10 career SES members have worked in the D.C. region.

Stier, though, said that concentration isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“You want your senior leaders to be interacting with each other across the organizational lines of agencies as much as possible,” he said.

For career SES members, the bigger issue is they rarely cross over to work at different agencies, usually opting instead to stay in a single agency or position for the majority of their time in the senior ranks of government. It’s certainly a problem, Stier said, but something that more remote work opportunities could help to improve, while addressing diversity as well.

“The original concept of the SES was this top-level group of executives that would move across government to address our biggest and most consequential challenges. I don’t believe that vision has played out,” Stier said. “You need to understand what you have — that’s the purpose of why we did this.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED