Exclusive

St. Elizabeths DHS consolidation plan: Where do we go from here?

DHS' headquarters consolidation project is bleeding money, behind schedule and doing anything but bringing components together.

Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on iTunes or PodcastOne.

Sitting at a plywood desk in what would become his successors’ personal office, former Homeland Security Department Secretary Jeh Johnson uncovered a secret: the future DHS headquarters at the St. Elizabeths Hospital Campus in Southeast Washington was the perfect place to take in the nation’s capital.

“It rivals the view from up at Arlington [National Cemetery],” Johnson told Federal News Radio. “It’s a great view of the city, it’s a great panorama.”

Johnson knew he likely wouldn’t be around to see the finished product, but with funding low and construction running behind, some wonder when that office view will ever be appreciated.

In Federal News Radio’s special report “St. Elizabeths DHS consolidation plan: Where do we go from here?” we look at the project’s status today, how it went from a promising idea to a real estate albatross, and what steps need to be taken to reach a successful consolidation.

At an impasse

Originally billed as a way to centralize leadership, improve operations and lower rent checks, the Homeland Security Department’s headquarters consolidation project is bleeding money, behind schedule and doing anything but bringing DHS components together.

DHS said it must go back to the drawing board with the help of the General Services Administration to revise its Enhanced Consolidation Plan, because it’s no longer up to date. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard, which operates under DHS, is warning against impractical plans to move more personnel into its headquarters on the campus. In addition, frustrated congressional watchdogs are looking for answers, despite the fact lawmakers repeatedly failed for years to fully fund the Bush and Obama administrations’ requests for funding to further the consolidation.

Johnson knows his trivia about the campus — the movie “A Few Good Men” filmed exterior shots there — as well as what to look out for when visiting [deer ticks] — but he also has some wisdom about the consolidation plan.

“The headquarters folks at DHS need a new office, the place they’re in now at Nebraska Avenue was always supposed to be temporary, and it’s substandard,” Johnson said. “In the consolidation project, we have to be careful not to do something that will have more of an effect of separating the component leadership from their own workforce.”

He said while he wouldn’t want DHS to insist that Customs and Border Protection or Federal Emergency Management Agency leadership be on the campus, which would dislocate them from the people they rely on on a daily basis, it was important to get some of the directorates to a new and centralized location.

During his brief tenure as DHS Secretary, John Kelly testified in June on Capitol Hill that he recognized the need for consolidation because the move would not only save DHS billions of dollars over the next several years, but it would also increase productivity and improve time management.

“It takes me half an hour from where I sit most of the time to meet with CBP or ICE or whoever and obviously a half an hour to get back,” said Kelly, who now serves as White House chief of staff. “Sometimes I do that two [or] three times a day. It kills either my time management or their time management. I do the best I can not to inconvenience the people who work for me. It would be an advantage to be more or less in one place.”

One of the people likely to oversee the effort is GSA Administrator Emily Murphy.

During her October nomination hearing, Murphy told the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs that GSA is working with DHS on a revised project plan to present to Congress on the “long-going process” of getting the department into its new home.

“I’ve visited the campus, I’ve seen the beautiful building they’ve built for the Coast Guard,” said Murphy, adding her pledge to make it a priority to give DHS a headquarters to meet its mission. “I’ve seen the work that’s taking place in the secretary’s office. I believe that’s going to be completed early next year, and so we’ll be able to move more of the DHS employees out there.”

But Murphy’s statement reflects the disconnect around the project.

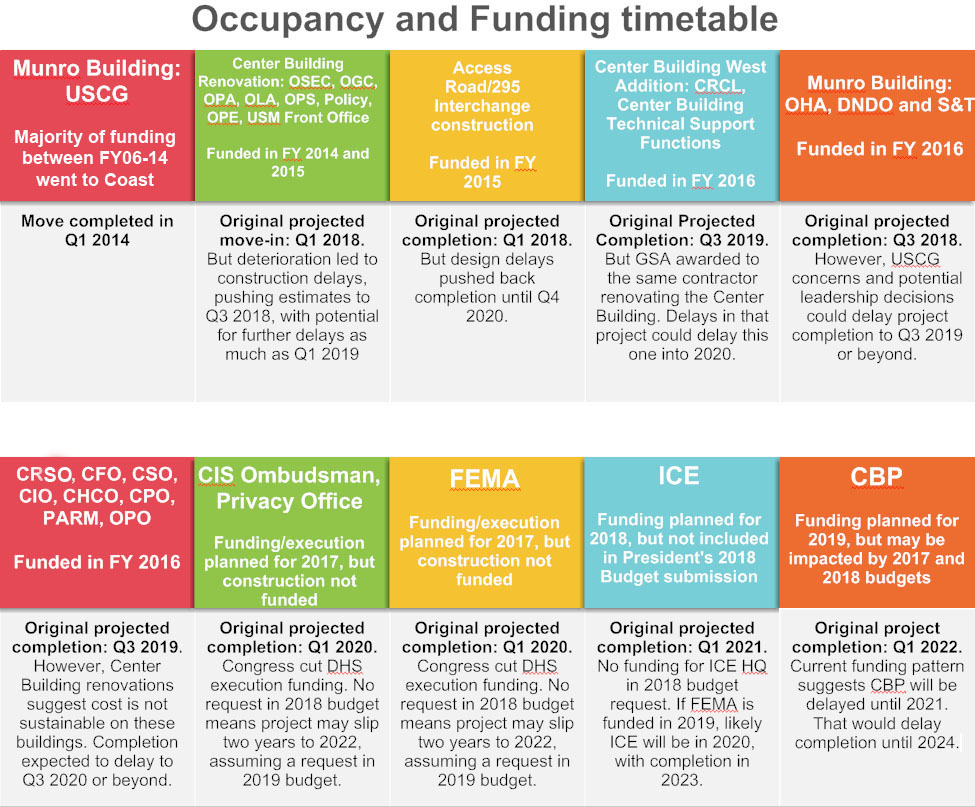

Information obtained by Federal News Radio shows that while the campus’s center building — the location of the secretary’s office — is fully funded and under construction, “excessive deterioration and structural repairs” caused the project to fall behind schedule and pushed the move-in date from mid-2018 to early 2019.

In fiscal 2014, DHS received $35 million for the headquarters consolidation, and the following year it got a total of $73 million — about $58 million for the consolidation and $15 million for support costs.

According to 2015 budget documents from DHS, the money “completes the IT infrastructure, IT equipment, outfitting, commissioning, decommissioning and move costs for the center building and the attached surrounding buildings comprising the center building complex.”

Information obtained by Federal News Radio shows that despite the funding, the center building’s construction is behind due in part to GSA’s misjudgment of just how badly the structure had deteriorated.

But the secretary’s office might be the least of DHS’ worries when it comes to the consolidation project.

The DHS consolidation plan directs the move of about 1,500 personnel from the Science and Technology Directorate (867), the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (331), and the Office of Health Affairs (249), into the Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building.

According to an Aug. 28 letter from DHS Deputy Under Secretary for Management Chip Fulghum to Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), housing OHA, DNDO and S&T “will provide potential direct rent savings to the Coast Guard of approximately $12 million annually.”

“In addition, full execution of the Munro Optimization Project precludes any need to construct a separate new facility to house these components, with an estimated cost avoidance of over $300 million in construction and tenant fit-out costs,” Fulghum’s letter stated.

The problem is that all three of those agencies’ leases expired in July 2017, and they are currently in a holdover status. What’s more, DHS and the Coast Guard answered questions about a move-in date in very different ways.

According to DHS Office of the Under Secretary for Management Spokeswoman Lauren Blakeney, the Munro Building is a “modern new facility with large open office floor plates that are eminently suited for reconfiguration to support flexible workplace strategies and increased utilization.”

Blakeney said the Munro building’s maximum capacity without utility systems upgrades is 5,100 people.

“There is wide recognition throughout the commercial and government sectors that traditional office space layouts (as Munro was originally configured) no longer represent the state of the market, given the expense of real estate, the widespread acceptance of flexible workplace strategies, and the increasing importance of building utilization (number of persons per usable square feet) as a defining measure of how the real estate portfolio is being managed,” Blakeney said in an email to Federal News Radio. “Therefore the department is looking at options to optimize the configuration of the building, which may include making utility systems upgrades, to ensure efficient and effective use of space.”

But the Coast Guard doesn’t see the same opportunity as its parent agency.

In an email to Federal News Radio, Coast Guard Chief of Public Affairs Capt. Howard Wright said the Coast Guard had “been working closely with the DHS Munro optimization team to fully illuminate the practicalities and challenges of a 40 percent increase in occupancy in the Munro building.”

“Despite our close coordination, we remain at an impasse over several issues,” Wright said. “For example, there are many inherent inefficiencies in the design of the Munro Building that were dictated by environmental, ‘viewshed’ [geographic area that’s visible from a specific location] and historical preservation constraints associated with the St. Elizabeths location. This design includes 150,000 square feet of corridors that are deemed usable space by the optimization team that cannot practically be used as workspaces from a work environment and fire safety perspective. The optimization team seeks to exploit these and other theoretical space as justification for moving 1,400 additional employees into the building.”

Wright said the Munro building was programmed with a capacity for 3,700 people but its current occupancy is 3,800 workers.

“The Coast Guard has continually communicated its requirement of capacity for 4,273 personnel to accommodate contingency, temporary program and expansion requirements,” Wright said in an email to Federal News Radio. “To help DHS and GSA meet their goals for reducing leased facilities in the National Capital Region, the Coast Guard relocated 600 personnel from Arlington, Virginia, to the Munro Building. This proactive move raised our occupancy of the Munro Building to 3,800 personnel — 100 above the building’s programmed level — reducing 160,000 square feet of office space from DHS’s inventory and eliminating $7 million in annual lease costs.”

GSA did not return multiple requests for comment about the cost of the holdover leases for DHS and the total amount of costs to taxpayers. While there is a monthly lease inventory, one must know the address of a particular lease to find out details about the lease space and rent price. A request to DHS for the locations of OHA, DNDO and S&T was declined on the basis of the information being “for official use only,” which is exempted from Freedom of Information Act requests.

Fulghum’s letter to Perry contains a breakdown of appropriations and obligated funds for the Munro Building’s optimization.

Of the $215 million appropriated in fiscal 2016 for the DHS consolidation, about $26 million of it was for the Munro optimization. DHS, as of Aug. 28, has financially obligated about $18.6 million to GSA. DHS has spent about $580,000 on the optimization, Fulghum said.

“An updated program of requirements (POR) has been developed for all planned occupancies in the Munro building,” Fulghum said. “A preliminary blocking/stacking plan and the initial design intent drawings for the facility have been completed. We are working with the U.S. Coast Guard to finalize the planned building density concept, and we expect this to be complete in December 2017.”

Blakeney said going forward DHS will work with GSA to develop a final design for the Munro optimization “based on the program of requirements for the Coast Guard and additional DHS occupancies, as well as current space standards.”

“Upon completion of the design effort and prior to proceeding with construction execution, DHS will — jointly with GSA — evaluate the potential adjustments required to achieve the planned consolidation and determine if these adjustments will have a significant adverse impact on the department’s mission effectiveness,” Blakeney said. “DHS will coordinate with GSA to advise Congress if the potential mission impacts rise to the level of requiring adjustments to the proposed DHS occupancies.”

A central hub

Disagreement around the Munro building’s tenants is just one of a series of issues that have plagued the consolidation plan. The worst offender — dogging the plan practically since its start — is funding.

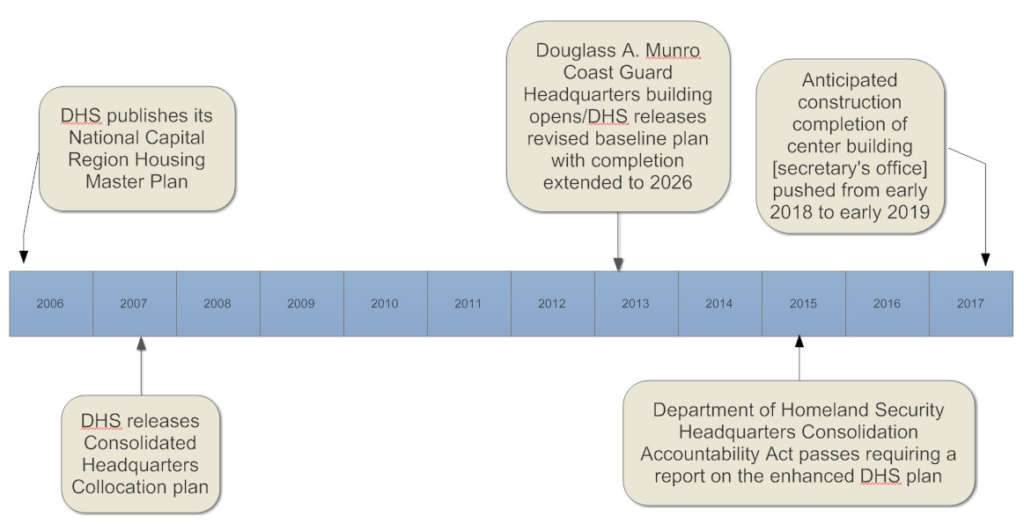

In 2006, four years after its creation, DHS published its National Capital Region Housing Master Plan. In the plan, the department flagged a need for 7.1 million square feet of office space for DHS headquarters, with two-thirds of it on a secure campus.

One year later, DHS released its Consolidated Headquarters Colocation Plan. At the time, according to a 2014 Government Accountability Office report, in the National Capital Region alone, DHS employees were spread out in 85 buildings at 53 locations.

The colocation plan, GAO said, “is based on the idea that the consolidated headquarters campus serves as a central hub for leadership, operations coordination, policy and program management in support of the department’s strategic goals.”

The original three-phase plan cost $3.26 billion, and proposed an eight-year build time with scheduled completion in 2016.

Between fiscal 2006 and 2014, the project received nearly $500 million in congressional funding for DHS, and another $1 billion through GSA’s congressional appropriations, GAO said, for a total of $1.5 billion.

Most of the funding through 2013 was spent on the Coast Guard’s move to the campus.

In 2015, after project delays and cost overruns, Congress passed the Department of Homeland Security Headquarters Consolidation Accountability Act. The legislation required DHS to provide Congress with updated costs and schedule estimates. The law took effect in April 2016, and gave DHS until September 2016 to produce a report.

Congress still is waiting for that report, according to an aide with the House Committee on Homeland Security.

“The law asked for current real property needs and what the future needs are of the department,” the aide said. “It asked for a construction plan, for costs, what the schedule would be, it asked for the lease portfolio for the department. Congress has really been kept in the dark on this. We don’t have an update, we don’t know the path forward on who all’s going to move and when that’s going to happen, what it’s going to cost. We want it to be a success, we want it to save money for taxpayers and help DHS be more efficient and more unified in its mission. Until they get us some answers, there are a lot of questions that remain.”

Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), chairman of the Homeland Security Committee, in September 2016 sent a letter to DHS calling the agency’s failure to produce the report “extremely troubling.”

“Even more concerning is that the committee is unable to obtain a straight answer as to why the report is late,” McCaul said in his letter. “Committee staff received information from the department claiming that the delay was due to the General Services Administration, while GSA relayed that the postponed release was the fault of DHS.”

In December 2016, Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.) released a staff report on the consolidation project. The report said as of last December the project had received about $2.3 billion of the $3.7 billion needed to complete the consolidation. The report highlighted that progress has been stymied by inadequate funding, and would continue to fall behind if it was not fully funded.

That prediction looks to be coming true based on 2017 and 2018 budgets.

GSA in 2018 requested a total of $790 million for all construction projects, including $135 million for continued infrastructure development for St. Elizabeths. But the Senate appropriations committee provided no funding in its version of the spending bill, while the House voted to only allow GSA to spend $7.9 billion of its Federal Buildings Fund, or a cut of about $981 million from 2017. The fund’s dollars are used to buy buildings and renovate existing structures in GSA’s portfolio.

DHS did not request any funding for the campus plan, and in fact its 2018 budget request includes a $178 million decrease in consolidation funding, which “reflects [the] decision to delay investment in construction, which will delay delivery of further segments of the consolidation project.”

The smart thing to do

Infighting and underfunding stain the project today, but the consolidation’s early days were colored with interagency collaboration.

GSA and DHS worked together to draw up a consolidation plan in 2009, targeting the West Campus of St. Elizabeths, located in Southeast Washington, D.C., for the site.

“It could accommodate the 4.5 million square feet of office space, plus parking, and was available immediately — two key requirements for DHS,” GAO reported. “GSA developed a Master Plan in 2009 that was to guide the overall development at the St. Elizabeths site. The plan was vetted through numerous stakeholders and received final approval in 2009.”

The plan required the future site house 14,000 personnel, as well as serve as the location for the headquarters for the Coast Guard and FEMA.

The site, according to GAO, would also be home to portions of:

- the Transportation Security Administration.

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

- Customs and Border Protection.

- the National Protection and Programs Directorate.

- the Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

- the Office of the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy, and the DHS Office of the General Counsel.

Federal News Radio learned that of the 10 milestones along the DHS component occupancy timeline, only one — the Coast Guard — had a completed funding status and move-in to the campus. The rest of the milestones range as far out as fiscal 2022 for construction completion and move in.

Carper, who asked GSA’s Murphy about the consolidation project during her nomination hearing, admitted that he used to think the idea “was a boondoggle,” but after spending time at the campus and talking with past DHS secretaries, he was convinced the plan was “the smart thing to do.”

“The folks at GSA were smart enough to figure out how to get more money, to save more money, by consolidating people rather than continuing to have them spread out all over the place,” Carper said.

Though DHS and GSA continue to struggle with the overarching consolidation plan, they are taking some steps forward.

GSA posted a solicitation for operation and management services for St. Elizabeths, and a source with knowledge of GSA procurements told Federal News Radio GSA planned on awarding a task order on IT services for the campus before the end of calendar 2017.

Some of DHS’ component agencies are having much smoother centralizations of their own.

TSA in August announced it would be moving its headquarters to Springfield, Virginia. And in late October officials with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services broke ground on the future site of the services’ headquarters in Camp Springs, Maryland. The building will consolidate about 3,000 employees spread out in six different locations around the Washington, D.C. area.

USCIS Director Francis Cissna told Federal News Radio the move “means a lot.”

“If everybody’s under the same roof, we’ll be able to talk to each other, collaborate, there will be a synergy that doesn’t exist now because we’re spread out across town,” Cissna said.

The site is roughly 7 miles, or a 15 minute drive, from the St. Elizabeths campus.

Then-acting Homeland Security Department Secretary Elaine Duke also spoke at the groundbreaking. It was a sunny and blustery day, and a red carpet was placed on the field to protect against mud puddles left from the previous night’s rain.

Duke comforted the audience of USCIS workers, saying she’d also been through a major office move when she worked for the Navy. While change was hard, she said having a singular headquarters in about three years would be “an amazing thing.”

“I think that you’ll find once you’re together, and you’ve adjusted your commutes, it’s going to be even better in terms of your ability to work and carry out the mission in the amazing way I’ve seen you do it over the past six months,” Duke said. “I’ll challenge GSA to a contest: Whether you move in or we move in to St. E’s first.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.