Proposed NIH budget boost spending for experimentation, examines lower grant funding for minority scientists

The 2023 proposal includes $12.1 billion additional dollars for pandemic preparedness, and an additional $5 billion to stand up the new Advanced Research Project...

Demand for speedier health innovations and a diversified biomedical workforce contributed to a proposed roughly 46% increase to the National Institutes of Health’s budget for fiscal 2023.

The President’s Budget Request included approximately $62.5 billion for NIH, compared to $42.9 billion the agency received in the 2022 continuing resolution, and $42.8 billion in the final 2021 budget. The request represents a 7.2% increase for research project grants, a 50% increase in the buildings and facilities appropriation, and a 5% increase for training.

The 2023 proposal includes $12.1 billion more for pandemic preparedness, and an additional $5 billion to stand up the new Advanced Research Project Agency for Health (ARPA-H). ARPA-H was first proposed in the president’s 2022 budget and is modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. It aims to use public-private partnerships for quicker support of results-driven, time-limited projects and innovations as a way to enable more experimentation.

“ARPA-H should expect that a significant fraction of its efforts will fail; if not, the organization is being too risk-averse. The best approach is to fail early in the process, by addressing key risks upfront,” NIH wrote in its 2023 budget justification to Congress.

Testifying before the House Appropriations Subcommittee for Labor, HHS, Education and related agencies yesterday, NIH Acting Director Lawrence Tabak said the request emphasizes large-scale investment because “the scientific opportunity presented itself,” due to either emerging technologies or areas of concern.

But ARPA-H still does not have a presidentially appointed director and Tabak could not give a firm deadline for hiring one. Therefore, Ranking Member Tom Cole (R-Okla.) asked why Congress should approve funding for an organization whose direction and leadership is still uncertain, at the expense of funding other NIH institutes.

“Our first step of course is going to be to build out the infrastructure, the administrative infrastructure of the organization. And from the practical standpoint, with the new organization within NIH we can draw upon some equities that are standard, that are used across HHS [and] indeed from other departments …” Tabak said. “We will certainly bring in a small group of senior operational people focused on the administrative side, but no program managers who will be driving the science will be recruited until the director is in place.”

Last July, then-NIH Director Francis Collins told the Federal Drive with Tom Temin that an ARPA-H director should have private sector and entrepreneurial experience, the ability to recruit several program managers in the first year, who understands design pitches and milestones to have dozens of projects going at once even with little results. Collins said ARPA-H was meant to operate in a more venture capital-type way, rather than as a traditional grant mechanism.

Subcommittee Chairwoman Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) expressed concern that ARPA-H leaves out smaller but still impactful projects. The estimated success rate for competing research project grants — which is the number of applications funded, divided by the number of applications received — was 19.8% in the 2023 request. Overall, success rates decreased from 18% in fiscal 2014 to 16.9% under the 2022 CR, which Tabak said was due to in part to an overwhelming increase in applications received.

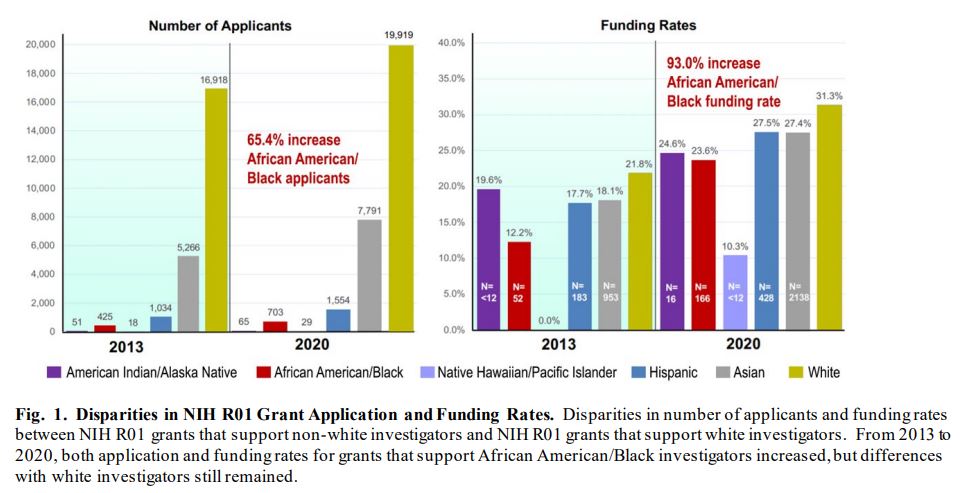

These success rates, however, obscure long-running disparities between white and minority scientists. For example, although the funding rates for African-American/Black scientists increased from 12.2% in 2013 to 23.6% in 2020, but that’s still behind the 31.3% funding rate for white scientists in 2020. The gap is exponentially wider when examining the number of Black applicants compared to white applicants.

A 2019 study of applicants for R01 research grants — the most common type of award — showed that African-American/Black applicants tend to propose research on topics with lower award rates. The president’s budget request proposes increased funding for its institutes on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Nursing Research; the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; and the Fogarty International Center, which all have disproportionate numbers applications from scientists in underrepresented groups as well as lower than average R01 success rates.

And because grant funding is often a factor in both hiring and tenure decisions for researchers and academic faculty, addressing these gaps is part of NIH’s UNITE idea generator, within the agency’s Equity Action Plan.

Every subagency at NIH has its own equity action plan that Tabak said would be updated periodically. Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-N.J.) asked about NIH’s investment in, and success rate of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives to date, including resources, and reviewers of grant applications. Tabak listed the Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation (FIRST) grant program to support cluster hiring and institutional cultural change, and NIH increased funding for the loan repayment program for researchers in areas of health for disadvantaged communities.

The president’s budget request also includes an additional $16 million for the chief officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity “to enhance NIH’s effort to diversify the national scientific workforce and expand recruitment and retention.”

Rep. Andy Harris (R-Md.) also asked Tabak why NIH has failed to reduce the median age of principal investigators for R01 awards despite years of attempts.

“Unfortunately institutions around the country increasingly want their new faculty hires to have bridge funding before they give them a permanent appointment on their faculty. And that was never an intended purpose of some of these transitional awards, but they become a surrogate of deciding who gets a tenure track position or not,” Tabak said.

As such, NIH launched the Stephen I. Katz Early Stage Investigator Research Project Grant, and established mentoring networks to encourage early stage and younger investigators to strive for that R01 award “sooner rather than later, despite what the old sages at their institution may be telling them: ‘Oh, you’ll never get that award, it’s too big, apply for a smaller, little award,’” Tabak said.

He added that students are entering graduate school later than before.

Meanwhile, it is important to make recruiting connections early, according to Roland Owens, director of research workforce development at the NIH’s Office of Intramural Research and a recruiter of principal investigators. In a 2020 interview with the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Owens said he struggles with turnover in his job.

“I learned in the last 12 years [by] making connections with staff [that] the people who are going to be at the university advising the postdocs and graduate students [are crucial],” Owens said. “Unfortunately, those people tend to have a lower profile on the web … and it can be a challenge trying to find those individuals to make connections with them.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Amelia Brust is a digital editor at Federal News Network.

Follow @abrustWFED