How three agencies cope with funding uncertainty under continuing resolutions

Programs at HHS, USDA and the Education Department remained fairly steady during continuing resolutions, GAO found.

Although continuing resolutions (CRs) can slow hiring, create funding uncertainty and cause administrative burdens, some agencies have found a few ways to circumvent the challenges and continue providing services without many major disruptions.

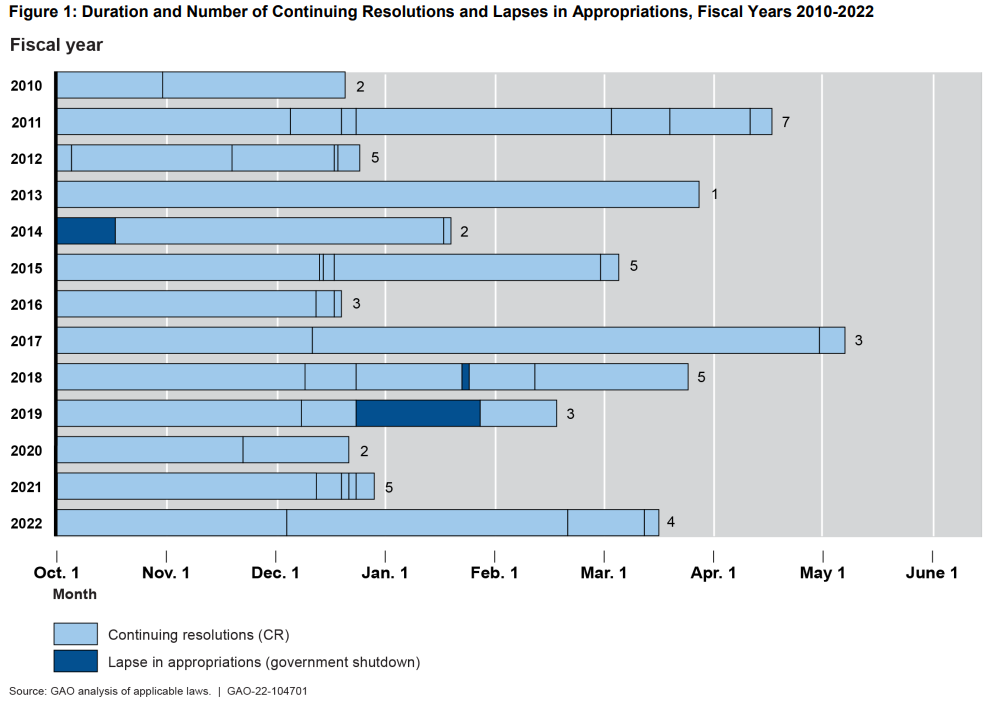

The federal government has operated on CRs for all but three out of the last 46 years, the Government Accountability Office wrote in an Aug. 1 report. Congress has enacted 47 CRs just since 2010, lasting about three months on average.

Congress often passes CRs to continue funding the government at the previous fiscal year’s funding level and to avoid a government shutdown. As members of Congress start to brace for a potential CR this year, GAO took a closer look at how some agencies manage to continue operating their programs during CRs.

GAO selected three federal programs to review, one each from the departments of Agriculture, Education and Health and Human Services. All three programs focus on providing services to individuals with low incomes or in underserved communities.

Across all three agencies, CRs do inhibit program operations, GAO said. Officials from the three programs said that they have all experienced administrative inefficiencies and limited management options during CRs, GAO wrote. Specifically, CRs often cause hiring plans to slow down or stop altogether. For instance, USDA’s Section 521 Rural Rental Assistance program, which provides rental subsidies, may not extend new hire offers during a CR.

Additionally, CRs limit the availability of travel funds for federal programs. For the Education Department’s Predominantly Black Institutions (PBI) formula grant program, a federal assistance program for PBIs, CRs limit employees’ ability to travel to the actual locations and monitor progress in the places where they awarded grants. In many cases, the program also hits delays in determining final funding amounts, which impacts planning for the program’s recipient schools.

“The officials added that grant recipients may have to discontinue activities or find other funding sources to cover activities until they receive final funding,” GAO wrote in the report.

In another example, officials in HHS’ Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which provides home energy assistance for low-income households, said funding uncertainty under CRs makes it difficult to plan operations during the summer months. Because of CRs, the program has to update its formula twice to determine grant allocations.

“According to agency officials, this formula is complicated, and time consuming, and creates additional work when calculated twice,” GAO wrote.

But, the agencies have found ways to mitigate some of the challenges and work through CRs “without major disruptions,” GAO wrote.

Since officials at all three agencies are accustomed to CRs, GAO said, they have strategies already in place to limit the negative effects. For instance, HHS officials at LIHEAP said they use specific procedures under a CR to issue grant funding within 30 days of the start of the fiscal year.

HHS officials in LIHEAP can also request and receive an “exception apportionment,” which lets grantees receive 90% of the previous year’s funding at the beginning of the next fiscal year, rather than the standard CR apportionment, GAO said. And, some grantees can get additional funding from state utility funds or the state budget.

At Education, the timing of the academic year aids the PBI grant program in maintaining smoother operations during CRs. Program officials have some buffer time between the start of the fiscal year, and when the funding actually goes to grantees, since the allocations don’t start for the grant program until the fourth quarter of the fiscal year. The program also has some flexibility to move around allocated funds for grantees.

“One PBI recipient we spoke with told us it can move grant funds between different PBI initiatives within its program by submitting a program budget amendment to Education,” GAO wrote. “Additionally, one PBI recipient told us that it can request and receive approval from Education that allows it to spend the remaining program funds that would otherwise be returned to Education after the original grant period ends.”

Multi-year appropriations also help agency programs spend funds throughout a CR. The multi-year funding gives the programs more flexibility, GAO said. At USDA, for example, the secretary can use a “reprogramming authority” to shift funds within a single appropriation during the multi-year funding period, if plans change during the time frame.

Programs that have multi-year appropriations are not very common, though. At HHS, the agency’s unaccompanied children and refugee programs are two of just a handful of programs that get multi-year funding.

Despite the workarounds and the ability to continue operations relatively well during CRs, the use of CRs still presents significant operational challenges, like funding uncertainty for agencies, GAO said.

For fiscal 2023, the likelihood of a continuing resolution is fairly high. Democrats in both the House and Senate have presented appropriations bills for the 12 required appropriations areas, but so far, the House has only passed six of the 12, and the Senate has yet to pass anything.

Congress has until the end of September to approve the spending bills in both the House and Senate. If any of the bills don’t make it through in time, then Congress would move to continuing resolutions for those funding areas.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED