Appropriators push back against plan to reallocate MILCON funds to border

House appropriators are not excited about the administration's plan to redirect military construction funds they've already allocated.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

The Trump Administration’s plan to redirect military construction dollars toward the building of a border wall saw bipartisan pushback on Wednesday. A key Republican warned that the move could jeopardize the longstanding discretion Congress has granted DoD, including the ability to reprioritize its own funds.

The White House plans to reallocate up to $3.6 billion from other construction projects for which Congress has already assigned funding in this year’s budget, once it has used other sources the president pointed to as part of his emergency declaration.

The Pentagon has not yet identified which specific projects would be affected, but says the money would only come from those that aren’t scheduled to be contracted out until the second half of this fiscal year.

But Congressional appropriators tend to guard MILCON funding in an especially zealous fashion: Unlike most of the rest of DoD’s budget, those dollars are allocated to specific construction projects in precise geographical locations, not to broad accounts or weapons platforms.

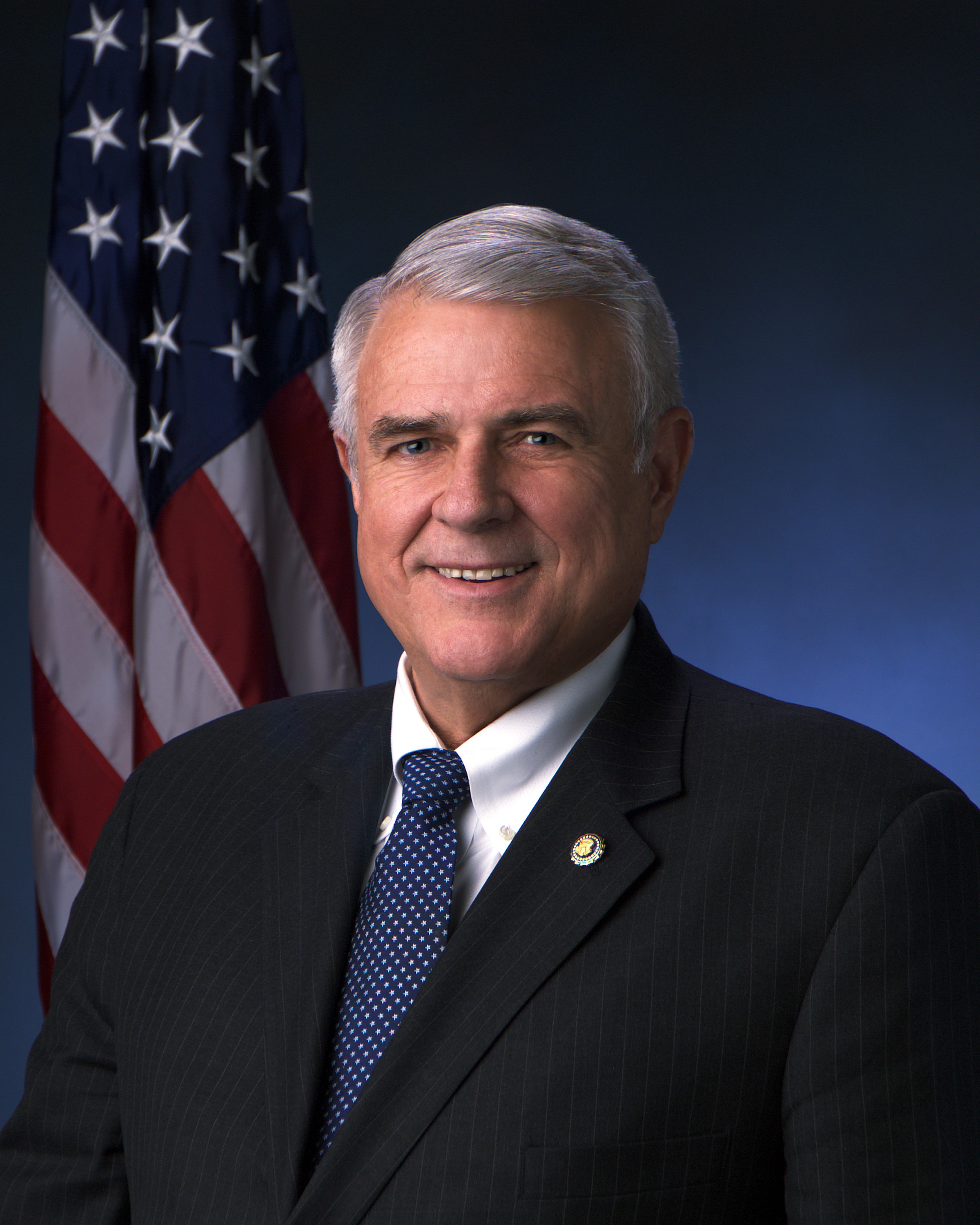

Rep. John Carter (R-Texas), the ranking member of the House Appropriations subcommittee on Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, cautioned that DoD could suffer a long-term penalty if the administration moves ahead with the plan.

“I understand that the department may not adhere to the cooperative traditions of the administration and Congress which have been developed over the past seven decades,” he said. “These traditions provide the administration with flexibility in the use of appropriated funds, ensuring congressional oversight. Are you aware of the new precedent being set? Does the department realize it could lose some, or a lot of the flexibility in spending appropriated funds?”

Carter’s questions, at a Wednesday hearing, were directed at Robert McMahon, the assistant secretary of defense for sustainment.

McMahon said he had not been involved in the policy decisions leading up to the emergency declaration, but that DoD was committed to fulfilling the president’s emergency mandate to the best of its ability while also minimizing impacts to its existing MILCON commitments.

“No currently authorized military construction projects will be canceled to fund projects under [the emergency authority], nor is the department considering any family housing projects as funding sources,” McMahon said. “This process is ongoing, and I stand ready to execute the necessary actions once a decision has been made. In carrying out this mission, I will continually assess the DoD capabilities and resources necessary to meet these mission requirements while mitigating impacts of military readiness and considering ongoing and future operational commitments.”

Potential impact on current projects

According to a statement the White House published Tuesday evening, the administration’s current border wall plans call for MILCON funds to be used only after it has spent the $1.4 billion Congress authorized in last month’s spending agreement, and after it’s exhausted another $3.1 billion in Treasury and DoD counter-drug funding.

DoD would need to take several additional steps before deciding which MILCON projects would be affected in 2019.

The administration’s position is that there would be no meaningful impact: any projects implicated in the transfer to wall spending would simply slip into the next fiscal year.

McMahon said the president’s 2020 budget proposal, due for release next month, will ask for extra MILCON dollars to replace the funding that had been taken away from projects Congress had authorized for this year.

Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-N.Y.), the chairwoman of the House military construction subcommittee, said the plan was a fairly transparent, backdoor attempt to get Congress to appropriate the same wall funding it had explicitly declined to pay for in the budget deal that reopened the federal government last month.

“You’re fooling no one,” she said. “I’m not sure what kind of chumps you think my colleagues and I are, but deferring and coming back in FY ‘20 to replace it leads to the same thing. You are taking money from vital projects that the military previously said were essential, spending that money on a wall, and then asking for the money to be backfilled later in the next fiscal year. We already had that debate, and the president’s proposal was rejected in a bipartisan, bicameral agreement.”

National emergency debate

The spending authority the president invoked with his emergency declaration gives him wide latitude to divert already-appropriated MILCON dollars, as long as he can justify that their use will go toward construction projects that are “necessary to support” military personnel that have been deployed in a war or national emergency.

Related Stories

But Carter’s comments signaled that even some Republicans view the administration’s approach as a serious encroachment on Congress’ power of the purse, and one that might warrant a crackdown on the flexibilities its appropriators have historically entrusted to DoD.

Each year, in ways not connected to the emergency declaration, the Pentagon has some latitude to reapportion funds between its various appropriations and to transfer money within those appropriations.

The guardrails within which it can move money back and forth without prior approval from Congress are technically set in each year’s appropriations bills, but do not change wildly from year-to-year.

The specific reprogramming and transfer rules vary across DoD’s spending portfolio, but the department reallocates about 3 percent of its $700 billion budget with those authorities in any given year.

In MILCON accounts, for example, the military services are allowed to remove an unlimited amount of funding from individual projects to pay for newly-identified needs in a given year. They do, however, need a sign-off from Congress’s authorizing and appropriations committees to move those funds to any single project that costs more than $2 million above what lawmakers have already authorized.

Those rules can be overridden when the president declares that there is a national emergency.

But Carter also questioned whether it was practical for the reallocated DoD funds to be put to meaningful use at the border.

“The 2019 Homeland Security bill provided for nearly $1.4 billion in border security projects. It will take at least two years to design and build them,” he said. “Why does the department need to take military construction funds now for projects that might not be ready for many years?”

For now, that question is unanswerable, because DoD still has not developed a clear picture of where the emergency authority the president invoked – Section 2808 of the U.S. Code’s Title 10 – might or might not apply.

“If the acting secretary of Defense, in conjunction with advice from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs identifies that there are appropriate projects that would fall under the 2808 authorities, and if a requirement is identified through that process, that information will be made available to the Congress,” he said.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED