Before the COVID-19 pandemic forced nearly all agencies to accelerate IT transformation, federal financial offices had already spent years rethinking the way they...

Before the COVID-19 pandemic forced nearly all agencies to accelerate IT transformation, federal financial offices had already spent years rethinking the way they do business and invest in emerging technology.

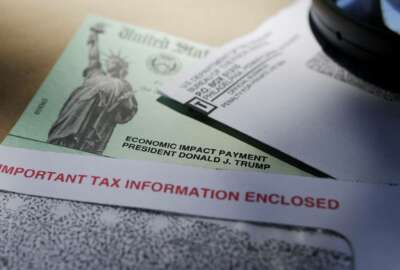

The Treasury Department’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service, for example, saw much of its five-point Future of Federal Financial Management Strategy pay dividends during the pandemic, when it disbursed more than 160 million Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) worth $270 billion.

Two weeks after Congress passed the CARES Act, the bureau had already distributed about half of all EIPs electronically, at one point disbursing more than 2 million electronic payments worth $150 billion in 10 hours.

Rhonda Kent, the bureau’s assistant commissioner for payment management, said Monday that by expanding the number of payments that went out electronically, the bureau was able to make payment speed a priority.

“These were urgently needed payments, we know that people needed the funds to pay rent, buy groceries, and otherwise pay the bills needed to survive during this pandemic.” Kent said during ACT-IAC’s virtual ReImagine Nation ELC conference.

Part of that work, migrating federal payments from paper checks to direct deposit, took decades. Kent said the federal government in 1975 issued more than 700 million paper checks, but last year issued only 50 million checks.

Because of this long-term migration from paper checks, the bureau was able to issue about 120 million EIPs via direct deposit. To maximize the number of payments sent electronically, Kent said the bureau conducted an interagency data analysis with the IRS to find banking information associated with 20 million federal benefit recipients.

Kent said the bureau has processed more than 2 million returned checks in a four-month period, and its Payment Integrity Center of Excellence continues to work with Treasury’s Do Not Pay Center, agency inspectors general and law enforcement agencies.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, meanwhile, has prevented over $1 billion in fraud over the past decade through predictive analytics capabilities.

Ray Wedgeworth, the director of CMS’ data analysis and systems group, said these predictive analytics capabilities have shown a strong return on investment since CMS implemented them in 2011. Some years, he said, the agency has seen a 10-to-1 return on investment in the system.

“With machine learning techniques, we’re getting better and better and refining those models to make them as actionable as possible,” Wedgeworth said.

The agency’s fraud prevention system, stood up in 2011, combs data on 11 million incoming claims every day, and flags suspicious billing from health care providers that program integrity contractors review.

“When the algorithms run, they put a level of risk on the provider — so they have risk scoring — and the unified program integrity contracts that we have come into that system, and then there’s information there for them about that provider. They’ll make a determination based on risk scores to begin an investigation,” Wedgeworth said.

CMS also operates a unified case management system that tracks investigations and their outcomes — such as referrals to law enforcement, or suspending payments to providers under review.

For better oversight into its grant-giving process, the National Science Foundation is standing up a blockchain solution. Mike Wetklow, NSF’s deputy chief financial officer, said the blockchain project stems from two goals in the agency’s “Big Ideas” strategic plan — harnessing the data revolution and preparing for the future of work.

The idea for using blockchain, he said, stemmed from a university partner’s complaint about navigating different financial management systems depending on the grant-issued agency.

“They said, ‘Why is it that we have to use NSF’s payment system here, Education’s payment system there, HHS’ payment system here, Department of Defense’s [payment system] there and Department of Treasury’s over there?’” Wetklow said. “I looked at the guy and said, ‘You know, you’re right.'”

Wetklow said the blockchain solution would ease the agency’s burden acting as a middleman for grants. The concept, he added, would also increase transparency and reduce fraud risk.

The Federal Reserve is developing a new service that will support instant payments.

The service, called FedNow, won’t be available until 2023 or 2024, but Kirstin Wells, an economist for the Federal Reserve Board, said the board approved the idea following demand from consumers and businesses.

“We’re looking 10, 15, 20 years down the road, when we expect that more and more payments will be made in this way. And so, we wanted to make sure that there was an infrastructure available nationwide to every bank that would support this growing use of instant payments,” Wells said.

Much like the Automated Clearinghouse Service the Fed and the financial industry created in the 1970s to support direct deposit, Wells said the Fed would provide the infrastructure to this new service, but would leave the rest up to the private sector.

“We offer the service to banks, and then they will build services that they offer to their customers. And they can work with fintechs, they can work with other agents to actually build out these services that face the end-user.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jory Heckman is a reporter at Federal News Network covering U.S. Postal Service, IRS, big data and technology issues.

Follow @jheckmanWFED