Half of agency supervisors say they’re confident they could remove ‘bad apples’

Agency culture and a poor understanding of the disciplinary process are some of the biggest challenges supervisors, managers and senior executives said they face...

Agency culture, poor human resources support and lack of legal expertise are the biggest barriers federal managers and senior executives face when trying to discipline or fire employees who act up, the Merit Systems Protection Board said.

And about half of agency supervisors and managers — on average — said they felt confident they would be able to remove an employee engaged in serious misconduct, according to MSPB, which last year surveyed more than 10,000 federal leaders about their ability to address misconduct in the workplace.

Yet the numbers differ slightly depending on who MSPB asked.

About 48 percent of non-managerial supervisors and 50 percent of managers said they would be able to fire an employee for misconduct, 69 percent of senior executives said they could.

“Whenever Congress, the President and agency leaders consider how to improve the civil service, and in particular how to improve the adverse action process, it is important to recognize that not every official has the same experiences when using the adverse action system or the same perceptions about how it operates,” MSPB said.

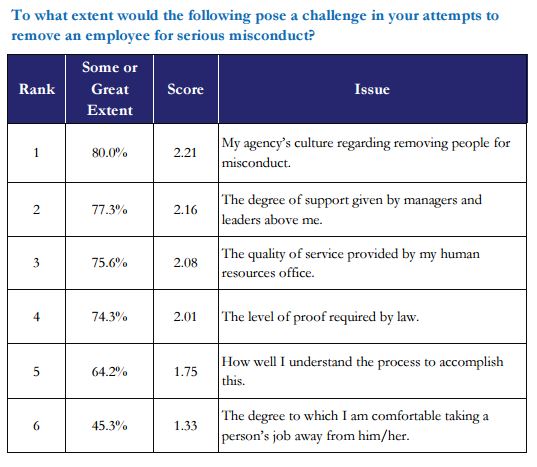

Specifically, MSPB ranked the top challenges that federal managers encounter when trying to fire an employee.

“There is not just one barrier that poses a challenge to removing employees,” MSPB wrote. “But it also shows that many of the strongest barriers that potential proposing and deciding officials face come from within their own agencies. The good news for agencies is that if agencies are the source of the problem, then they can be the source of the solution.”

Most managers, or 80 percent of them, believe their agency’s culture and the support they receive from the people above them are the most difficult challenges in firing employees.

Bill Wiley, an attorney and former chief counsel to the chairman of MSPB and now co-founder of the Federal Employment Law Training Group, said agency managers often feel like their supervisors won’t back them if they decide to fire one of their employees.

“The head of [an agency] isn’t sitting there saying, ‘don’t fire people,'” Wiley said. “But what he’s doing is he’s empowering his legal staff to say yes or no to these actions that lower management wants to take, and then that becomes the culture, as it’s both created and applied by the legal staff.”

About 60 percent of supervisors said their understanding of the adverse action procedures is at least one barrier that hinders their ability to fire someone.

Managers are also confused about how much evidence they need to bring to prove an employee’s misconduct, the agency said.

“This item is particularly interesting because, as we have reported before, officials who actually propose and decide to implement removal actions overwhelmingly use a much higher level of proof than the law requires,” MSPB said.

But Wiley said this confusion also stems from the agency’s legal counsel.

“There should be an adviser, whether it’s an HR specialist or an attorney, explaining to that person, you don’t need that much proof,” he said.

Though half of surveyed supervisors and managers said they felt confident that they’d be able to fire an employee, many said preventing and then addressing misconduct within their workforce was not an incredibly difficult part of their jobs. Those tasks ranked 14th and 15th, respectively, on MSPB’s difficulty ranking for management tasks.

Dealing with poor performers, however, is more challenging. Managers ranked addressing performance issues as the 10th most difficult task.

Managers said obtaining a quality pool of job candidates is their most difficult task.

While addressing misconduct is not the most challenging task for managers, most supervisors said they believed it should be easier. Roughly 78 percent said it’s harder than it should be to fire employees for misconduct.

Supervisors largely agreed that protecting employees’ rights is important, but MSPB’s survey shows some disagreement in the management community about how many civil service rights employees should have.

About one-third of managers said federal employees have too many rights and one-third said they do not. The final third neither agreed nor disagreed with that statement.

Roughly 44 percent agreed with this statement: “Knowing that the employee can grieve or appeal a serious adverse action makes me feel more comfortable about taking such actions.” About 25 percent disagreed.

MSPB will release additional results from the survey in future reports, including one on federal human resources services. The agency has conducted other surveys in the past, but this is the first time MSPB has explicitly asked agency managers about their comfort and ability to fire an employee, Wiley said.

MSPB seems poised for future congressional debates or conversations on civil service reform, he said.

“In some ways they seem to be fighting for their existence,” Wiley added. “Starting around 2010, 2011, the board began to be seen as a real impediment to holding people accountable. In other words, why should we have MSPB; it keeps people from running the place?”

More Workforce News

MSPB would argue — and has — that it upholds agency punishments most of the time.

Managers’ views of MSPB itself didn’t get specific mention in the agency’s report. But some agencies have expressed their frustration with the board in recent years. Lawmakers and the Veterans Affairs Department itself grew particularly frustrated in 2016, as they watched MSPB overturn punishments for three senior executives at the VA under the VA Choice Act.

That irritation prompted both VA and Congress to consider making changes to the standard of proof that the department would have to provide, in addition to moving some VA health professionals from Title 5 to Title 38.

MSPB currently lacks a quorum, as the agency has one voting board member. President Donald Trump designated Mark Robbins as the vice chairman of the board. Robbins will carry out the chairman’s duties until the President names two more board members. Former MSPB Chair Susan Tsui Grundmann resigned in January after serving in holdover capacity when her term expired back in March 2016.

The board cannot rule on employees’ petitions for review until it has at least one other member. Administrative judges and regional MSPB offices will continue to issue initial decisions.

The board also made a new report on adverse actions available to the public, which describes how the civil service adverse action system works.

“The board has a responsibility to ensure that Congress and the President have the information they need to make well-informed decisions about the civil service,” Robbins said in a Feb. 14 statement. “That is why we first published these materials while we still had a quorum, before Chairman Susan Tsui Grundmann departed. Now that Congress is back in session and the civil service committees have begun their work, I have sent copies of these documents to the House and Senate committees’ chairman and ranking members.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED