Navy says its readiness is improving, but progress is fragile

The Navy tells the Senate Armed Services Committee that a change in funding could hurt its trajectory on readiness.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

After three years of increased budgets to “restore readiness,” the Navy is seeing some measurable results. The potential of a return to sequestration in 2020 – which would translate to a $26 billion cut for the Department of the Navy – could devastate the progress it’s made, top Navy and Marine Corps officials told Congress.

Service leaders marked a line in the sand against the possibility of a legally capped budget or a lapse in funds during testimony before members of the Senate Armed Services Committee on Dec 12.

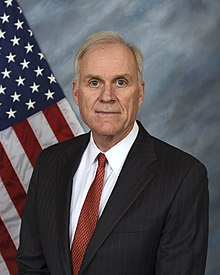

Richard Spencer, Navy secretary, likened the Navy’s current readiness status to riding a bicycle: It takes a few pedals to find your balance. The Navy is now in that vulnerable position of heading in the right direction, but any slight setback could harm progress, Spencer said.

“The weather vanes are all pointed in the right direction,” Spencer said. “Urgency is the message we have now. You are seeing improvement, but the rate of improvement must increase and we believe we have plans to address that. The foundation for restoring readiness and increasing lethality has been set, but we must build on this.”

While the Defense Department is safe from any government shutdown in 2019 — Congress passed an appropriations bill to fund it for the full year — there are still threats to the amount and timeliness of the funds the military will receive for fiscal 2020.

For the 2020 budget, Congress will once again contend with the Budget Control Act (BCA) caps, which was on reprieve for the previous two years due to a budget deal. This time Congress will have to come to a deal to raise the sequestration caps while under a divided Congress.

Democrats are likely to demand increases in domestic spending in return for raising the caps on defense spending in 2020. They will have much more leverage than in the previous deal now that they control the House.

Funding beyond 2019

Furthermore, judging by Congress’ history, it’s possible the military will have to operate under a continuing resolution or even contend with a shutdown before securing 2020 funding.

All of those options, Navy leaders said, would throw the service off of its upward trajectory.

“In order to affect our goals we must — we must, ladies and gentlemen — have consistent funding,” Spencer said. “Any break in that consistency will have dire effects on the process and progress that we have made to date.”

After receiving a 2017 supplemental budget and increased budgets in 2018 and 2019, Spencer and the Navy and Marine Corps’ uniformed leaders said they are seeing quantifiable results in some areas important to the services’ readiness.

“In the past 3 years we’ve reduced lost days to maintenance in the public shipyards by 11 percent,” Spencer said. “In the past two years we have reduced workload carryover by 46 percent, which reflects our efforts to balance workload to capacity in order to improve productivity.”

Naval shipyards reduced the time it takes to develop a worker by at least 50 percent.

Last year, Marine air squadrons achieved readiness rates above the service combat readiness standards for the first time since sequestration in 2013, and average flight hours per aircrew increased from 13.5 per month in 2016 to 17.9 in 2018.

However, not all areas have seen improvement.

John Pendleton, the director of Defense Capabilities and Management at the Government Accountability Office explained some areas of the Navy that are particularly vulnerable to funding breaks or declines.

“Completing maintenance on time has proven to be a wicked problem,” he said. “Since 2012 the Navy lost more than 27,000 days of ship and submarine availability due to delays getting in and out of maintenance. 2018 was particularly challenging with the equivalent of 17 ships and subs not available because they were waiting to get into or out of maintenance.”

Related Stories

Additionally, Pendleton worried the Navy is not staffing its ships enough to cover the workload, which is leading to some sailors working 100 hour weeks.

Spencer said sequestration would “simply knock” the Navy down.

Gen. Robert Neller, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, said his service is making progress, but it is in a critical time.

“I can show you quantifiably that our readiness is improving, but we have a unique problem. We are at an inflection point for our nation,” Neller said. “We have to maintain the current operations and those are being reviewed and looked at. We have to modernize the force that’s been at war for 17 years and we have to prepare for something we haven’t had to prepare for since the Cold War, to fight a peer adversary.”

Neller said going back to BCA-level funding would mean more than just grounding the Blue Angels. Sequestration would mean units deploying later, changes in the size of the force, less presence around the world and delaying almost every single acquisition program underway.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED