Five ways to improve FOIA estimated completion dates

Agency public information officers can take advantage of setting estimated dates of completion to identify unwanted pages and speed up processing times.

As backlogs for Freedom of Information Act requests grew during the pandemic, some agencies found success limiting processing times. Now, those agencies are offering best practices to improve the public information request process and make it easier for records custodians to calculate estimated dates of completion (EDCs).

FOIA, which celebrated its 56th anniversary on July 4, mandates agencies provide EDCs on all public information requests, although many agencies do not provide them, Alina Semo, director of the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), said.

The agency’s annual meeting on June 29 comes after OGIS issued their annual Report for Fiscal Year 2021. OGIS is the congressionally mandated agency in charge of reviewing FOIA policies, procedures, compliance and improvement.

The report said OGIS handled 4,200 requests for assistance from both FOIA requesters and agencies. OGIS sees a fraction of the overall public information requests filed to various agencies.

The FBI, alone, has about 30,000 incoming requests each year, Michael Seidel, the agency’s chief FOIA officer, said.

As agencies are still dealing with the fallout from the pandemic, OGIS reported the number of requests for OGIS assistance involving delays jumped 73%, from 220 cases in 2020 to 380 in 2021. In 85% of the requests about delays, the requester could not get an estimated date of completion from the respective agency.

“Our assessment found that agencies were challenged even before the pandemic began to provide EDCs and the agency’s responses to such requests were mixed,” Semo said during the meeting.

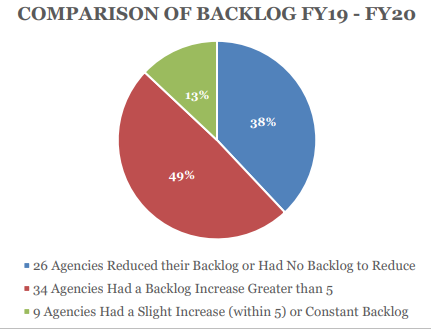

The Office of Information Policy’s Summary of Agency Chief FOIA Officer Reports for 2021 said by the end of fiscal 2020, 34 agencies had their backlog increased by more than five requests. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs had more than 1,000 requests backlogged in 2020, the agency’s 2020 annual report said. The VA closed their 10 oldest appeals in 2020.

A request is backlogged when it is pending beyond the statutory time period for a response. For requests, the statutory time period is 20 working days from receipt of the request, unless there are “unusual circumstances,” as defined by the law, in which case the time period may be extended an additional 10 working days.

Of the 35 agencies with backlogs, 14 processed more requests than the previous fiscal year, OIP said. Although, 26 medium and high volume agencies reported they reduced the number of requests in their backlog.

FOIA officers from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Postal Service and the FBI laid out five tips agencies may want to consider implementing to reduce backlogs, including being proactive in alerting requesters when records custodians delay EDCs and creating negotiation teams.

Proactive communication about EDCs

Among the most common recommendations from the panelists was open and proactive communication between records custodians and requestees.

Gregory Bridges, chief of the disclosure branch of the records management division at FEMA, said proactive communication begins with agencies providing an EDC.

At FEMA, Bridges said getting record custodians comfortable with the concept of providing an EDC was the first struggle. He said agencies with similar issues should base the EDC off the time it would take to complete the request if they worked on nothing else.

“There’s nothing wrong with telling a requester ‘we think it’s going to be ready by this date. If we don’t think we can meet that date, we’ll definitely reach out.’ But you have to reach out. If you’re saying, ‘the 25th,’ by the 20th or the 24th, you should have an idea of if you can meet the 25th and if you know you can’t, let the requester know before the 25th,” Bridges said at the annual meeting.

In his time at FEMA, Bridges said he finds the main complaint from requesters is thinking they have been forgotten. “Even if they don’t like the date being extended, at least they know that you’re actively working on it,” he said.

He also said providing a clear timeline and EDC to requesters may encourage them to reduce the breadth of the request if they request more records than they need and want the records by a certain day.

“Even if you have to extend [the EDC], then that could be another opportunity to narrow the scope,” he said.

Record custodians at FEMA find it helpful to explain to requesters exactly what they are looking for in case it’s more than they need.

“One of the things we do at our agency is explain to requesters why searching for all of the emails with the word hurricane during hurricane season might produce more records than you’re actually looking for,” Bridges said

Similarly, Nancy Chavannes-Battle, the deputy chief FOIA officer at the USPS, said providing partial responses when files become available if requests are taking longer than originally estimated.

At the FBI, an online tool can tell requesters what stage their request is in and direct them to a PIO and the negotiations teams, who can answer questions in order to keep communication open throughout the process.

Negotiations teams

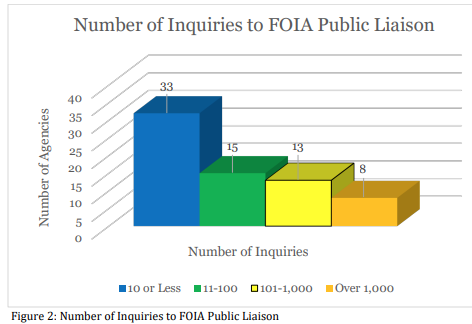

The FBI’s negotiations teams review the files and interact with requesters to answer questions. In fiscal 2022, the FBI received over 14,000 emails and over 1,100 phone calls about requests, Seidel said.

“We find that a lot of our requesters engage with our public information officer to get more information about the request and that’s where the discussion about the EDC really happens,” Seidel said.

Negotiations teams ask requesters what they are looking for such as a specific event, a date range or an interview in order to stop processing unwanted pages, which, in turn, provides records faster.

“We’re able to serve more requesters and give more requesters more information more frequently,” Seidel said.

Seidel said the negotiations process has eliminated the processing of over 66 million unwanted pages that were originally requested.

Automated EDC organization

The FBI FOIA office uses automated multitrack processing programs to estimate the average number of days it takes to complete a request.

They organize their requests into four tracks based on page size: small, medium, large and extra large. At the agency, the small track includes requests between 1 and 50 pages and the medium track is 51-to-950 pages, although other agencies who implement similar processes can change track size as needed.

“We’ll look at those dates within those queues of the dates requests were opened, we’ll do the math and compare them to the dates they were closed and we’ll come up with that average number of days it takes to complete a request within that queue,” Seidel said.

The FBI FOIA office runs those audits every six months. Seidel also said an original challenge when implementing the program was deciding the right frequency for running the audit.

Estimated dates of completion: They’re not just for the requestor

Although EDCs are required by the FOIA, Bridges says, they do not only benefit the requester.

“You should be establishing EDCs, just for your office’s knowledge,” Bridges said. “It’ll help you gauge your output, what can you expect to go out the door. So even though this does benefit the requesters in a big way, it can also benefit your office from managing your requests in a big way too.”

He said every agency should incorporate the EDC timeline into the processing of all their records.

“If you put all of your requests on an EDC that can also help you factor in how long it’ll take you to work on a particular request. Because you’re considering your current workload,” he said.

Chavannes-Battle, from USPS, said PIOs should break down what increases the time of requests when setting EDCs, such as requests needing to be referred to other offices, going through corporate communications and legal departments.

Connect with agency leadership

The OGIS assessment found support from agency leadership to be critical to the success in meeting requirements, such as providing EDCs.

At USPS, Chavannes-Battle says their staff training program is an important way PIOs connect with agency leadership to function smoothly.

At FEMA, Bridges says training staff to work with attorneys at agencies helps set EDCs and return records quicker “especially when you’re dealing with senior managers who aren’t familiar with the FOIA process, and you’re coming into their program, trying to tell them why they need to make our work a priority against their work.”

“It really is just understanding what that particular manager or leader cares about when it comes to the FOIA process,” he said. “Do they care that they’re in compliance? Some do, some don’t. Oftentimes, they care about not getting in trouble. They care about not having to spend money, they care about not having to get sued.”

In FEMA’s FOIA department, PIOs treat senior managers as enforcers to get their staff to comply with FOIA requirements, he said.

Benefits of recommendations

FEMA began to implement the new procedures in 2018. Bridges says the agency has only been sued twice over FOIA records since implementation. While appeals over denied requests were previously between 1,200 to 1,700, they fell to around 45 each year since.

“It isn’t because we don’t get those kinds of people [watchdogs], it’s because of implementing this new procedure and really establishing these response dates,” Bridges said. “That’s part of setting the expectations with the requesters so once we got people familiar with it, we really started to see appeals and challenges to our final responses reduce significantly.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Abigail Russ is an intern with Federal News Network.