GSA’s 18F organization created an ATO sprint team that streamlined the process and reduced time to complete an ATO from six-to-18 months to 30 days.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Quick, which federal cybersecurity process is most costly, takes the longest and is hated by most federal chief information security officers, program managers and chief information officers?

If you answered, the Authority to Operate (ATO), you’d probably be correct.

For an agency to get a system from test and development to full production it must have an ATO, meaning the system owner must approve the risk-based assessment and security controls that are running on top of the system.

For many system owners, obtaining an ATO can take a year and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and while it is supposed to be good for a year, without continuous monitoring, it really is good for about five minutes once it goes online.

“It’s also quite common for the specific steps to obtain an ATO to differ from person-to-person, which ultimately encourages everyone to take many unnecessary extra steps ‘just in case,’ further prolonging the process without adding benefit,” wrote Nick Sinai, a former federal deputy chief technology officer and now a venture partner at Insight Venture Partners and an adjunct faculty at Harvard, in a Medium post July 2017. “Further, the weight of the process strongly discourages ever changing a system, which would trigger the ATO process anew; this stagnation leaves most government legacy systems at great risk for vulnerabilities, not to mention lost innovation and productivity.”

But what if an agency could get an ATO in 30 days or five days, or one day? That idea was a dream industry experts and federal executives have talked about for years.

Today, that dream is much closer to reality.

When a need meets the desire, amazing things can happen, especially in government.

The General Services Administration’s Technology Transformation Service had a backlog of 30 systems that needed new ATOs. Aidan Feldman, an innovation specialist at GSA’s 18F organization, said there was no way TTS could clear out that backlog if every ATO took six-to-18 months.

So 18F did what it is known for, taking a big hairy problem and breaking it down into consumable pieces.

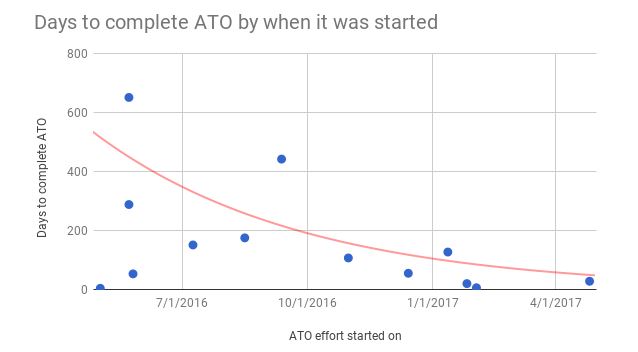

Feldman said 18F created an ATO sprint team that streamlined the process and reduced time to complete an ATO from six-to-18 months to 30 days.

“The real key to this ATO sprint team was getting everyone in the same room. We all work remotely so in this case it was a virtual room,” Feldman said in an interview with Federal News Radio. “If we have more conversational back and forth in real time, it increased the understanding on both sides, and greatly reduced the overall time to complete.”

18F reduced the backlog of systems that needed new ATOs in 18 months, and maybe more importantly, created a repeatable process.

The dream is even more real over at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Just over a year ago, Jason Hess, the one-time cloud security architect and now vice president of global security at JPMorgan Chase, excited the federal IT community by talking about getting an ATO in a day.

While NGA hasn’t met that goal, Matt Conner, NGA’s chief information security officer, said after the Aug. 1 Meritalk Cyber brainstorm event in Washington, D.C., that the agency has realized an ATO in as little as three, five and seven days.

“We are continuing to build the telemetry necessary, the business rules, the promotion path for code committed to our dev/ops pipeline and to promote that as quickly as possible to operational,” Conner said in an interview. “We still haven’t realized the one-day ATO, but it’s out there.”

Conner said the NGA is so excited about the potential of reducing the ATO process down even further, there is discussion about an instant approval.

“We are continuing to shore up our continuous monitoring and telemetry capabilities for new capabilities that are developed so that we can really, really quickly authorize something or ATO something and move it directly into step 6 of the Risk Management Framework and continue to monitor changes to that baseline in operations,” he said. “The ATO-in-a-day solutions have always applied to our dev/ops environment. So these are capabilities developed on a platform, in a handful of languages that we prescribe with a handful of orchestration services, according to a handful of profiles that we’ve defined. It sounds like a lot of limits, it’s not. I would consider much more guardrails than limits.”

The Office of Management and Budget and others have recognized over the years that the ATO process was broken. Back in 2017, OMB said it was running a pilot program to consider other approaches to shorten the authority to operate (ATO) life cycle and may potentially look at a “phased ATO.”

It’s unclear what happened to those pilots around a phased approach to an ATO as OMB never publically discussed those results or findings.

The attempt to fix the ATO process has been an ongoing project for OMB.

If you go back to 2013 in the annual FISMA guidance, OMB told agencies they had four years to get to continuous monitoring of systems, which would change the ATO process by making it an infrequent event to one that happens every time there is a change to the system.

Now despite these policy changes, the ATO process remains arduous and costly. Many agencies have moved to approve systems most regularly, in most cases annually.

The one thing about what NGA and GSA accomplished is the ATO in a day or 30 days works only because the organizations set specific limits. Conner said big monolithic systems that continue to use the waterfall approach to development will never enter the quick turnaround security conversation.

For 18F, the limits came from almost every system running on the cloud.gov platform, meaning a specific set of security controls that came with the platform-as-a-service were easily agreed upon and checked off the list.

The sprint team also used standardized ATO tools for architecture diagrams, vulnerability scanning and logging, according to Feldman’s blog post from July 19.

Feldman said one problem with the ATO process is the communication was slow and usually by email. 18F set up a dashboard to make progress easy to track, and created these virtual teams that got together to hash out problems or challenges.

“Teams coming in may not have compliance experience so sending them to FISMA or other large daunting paperwork about the ATO process is not going to be the easiest way to get into it. So, we standardized and documented our process including a checklist about of what is expected going in, Feldman said. “Similarly for those systems, if every system coming in to the assessment is running on different infrastructure, then, for the assessors, there is no consistency and they don’t know what to expect. It’s the assessor’s job to understand what’s going on in the system and so it takes longer if they have to relearn a new technology every time. We found the more that we are able to inherit between systems and share the best practices of how you configure it, and then the shared language around how you explain how the system is working, having all that more consistent helped the process on both sides.”

Over at NGA, Conner described a similar experience.

“These are code or algorithms or layers to our geospatial information system applications,” he said. “The process is really applying a lot of business logic to the telemetry we can gather and measure. We are looking at code quality, code dependency, static and dynamic testing, we are looking at targeted profiles that we’ve built that apply a set of controls to a workload and it’s all cloud based and platform based.”

“I’ve always likened the ATO in a day process to a speed pass on the local toll roads. You can real fast with your speed pass after you have gone online and registered your car and registered your transponder, tied it to a bank account and affixed it to the inside of your windshield in a certain place, then you can go real fast. If you don’t do any of those things, you don’t go real fast and you stop and give people money,” he said. “It’s the same thing. We have a set of design patterns; we’ve got a set of orchestration services; we’ve got a set of compute environments so if you are in that space and you want to play by our standards inside these guardrails, we will accelerate you as fast as we can. If you want to do something bespoke, you will have a different process.”

Feldman said 18F’s process is not magic or anything special — it’s just a matter of getting people in the same room as willing participants, documenting the process and your learnings, and setting the same expectations on all sides. That will go a long way, he said.

“I don’t think it will get down to an hour or anything like. The ATO process is there to make sure you are doing your due diligence securitywise and that can’t go away completely and I don’t think it should go away completely,” he said. “What I do hope to see is a reduced effort for the teams and the assessors to complete the ATO. That comes with better tooling, better documentation and better tracking of these projects as they go through so we can get ahead of problems as they come up.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED