The Department of Homeland Security released a solicitation through its Commercial Solutions Opening pilot to see if vendors have artificial intelligence tools to...

Let’s talk about the word “satisfactory.”

For most of us, the first thing that comes to mind is the grade of a “C.” If you received a “C” in high school, your parents probably asked you what happened, as if satisfactory wasn’t good enough. Of course, there are some of us in certain subjects, say math, where a “C” was excellent.

But for the most part, getting a “C” in many households was unacceptable.

That word “satisfactory” is at the crux of what is wrong with the Contractor Performance Assessment Retrieval System (CPARS).

Too many contracting officers are saying a vendor’s performance is satisfactory for two main reasons: A lack of time to explain why the contractor was outstanding or exceptional, and to avoid any lengthy back-and-forth if a rating is below average or poor.

But as Greg Rothwell, the former Department of Homeland Security’s chief procurement officer, said at a recent event on CPARS, “If you are a vendor, getting a satisfactory kills you.”

This is because contractors and contracting officers should be using CPARS as one way to differentiate themselves from their competition. But if everyone is rated “satisfactory,” then CPARS loses most of its value.

Not everyone believes earning a satisfactory rating is a killer.

Jeff Thomas, the director of the acquisition and grants office at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said vendors shouldn’t see receiving a satisfactory rating as a bad thing.

“When we have vendors who deliver on time, that is satisfactory,” he said at the Professional Services Council event. “It will not be a killer for you. People looking at CPARS will be able to differentiate between what was a complex project and what wasn’t.”

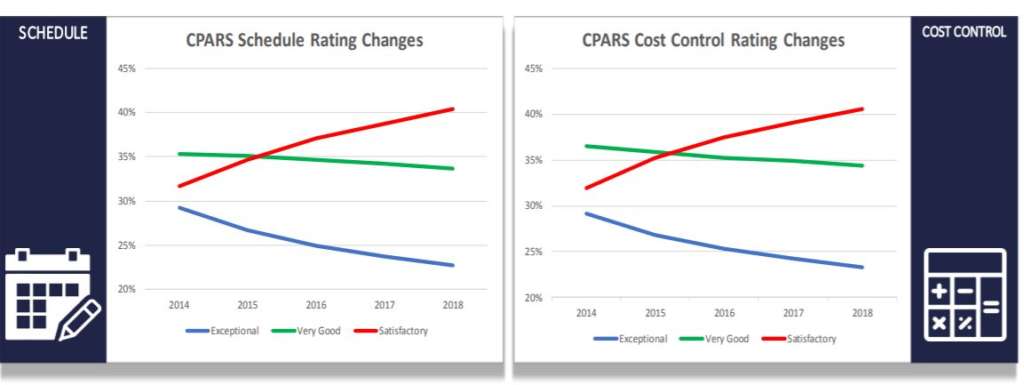

Data compiled by GovConRx, an contractor consultancy, found between 2014 and 2018, the number of satisfactory CPARS ratings increased across all four metrics — quality, management, schedule and cost control — while the number of exceptional and very good rating steadily declined.

“CPARS are rising in importance as many agencies have increased their reliance on past performance questionnaires,” said Mike Smith, a former DHS director of strategic sourcing and now executive vice president at GovConRx. “This is why vendors need to get agreement with their government customers on what it means to get an exceptional CPARS rating. What are the additional things you need to do to get an exceptional or very good rating? The government will not answer that up front, but it’s imperative for industry to work with your government customers throughout the contract. The bottom line is that CPARS is an active element to managing excellence, and not just a reporting or compliance activity.”

Shanna Webbers, the IRS’ chief procurement officer, agreed with Smith, saying vendors should ask their program managers what excellence means to them.

“While it’s beaten into the federal government that satisfactory is good, how do you get an excellent? When I get a new supervisor, that is what I ask. What do I need to do to show exceptional performance? Having those conversations at the beginning, and the middle of a program are critically important. You help document what that is and at end of the fiscal year, you show specific results to prove you were excellent.”

It’s also that thinking of making CPARS more than a reporting or compliance activity that is behind DHS’ recent solicitation under its Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) pilot program.

“The government desires one or more demonstrations of a proof of concept/viable prototype to determine the extent to which artificial intelligence can assist contracting officers conducting past performance evaluations in making efficient and effective use of CPARS information,” the solicitation states. “The government hopes, as a threshold, that the demonstrations will show that AI can help the contracting officer identify which records in CPARS contain the most relevant information to the past performance evaluation in question. The government also desires data-driven and evidence-based recommendations about opportunities to improve the data quality of the past performance information inputted by contracting officers into the CPARS, based on the provided test data set and informed by the development of the proof of concept/viable prototype.”

The CSO approach is in the same vein as the increasingly popular other transaction agreement (OTA) where the agency is using a streamlined approach to test out or invest in innovative ideas.

DHS says it will award up to five CSO agreements worth $50,000 per awardee to test their AI or machine learning technology against approximately 1,000 records of about 50 contractors. The agency said the test data is actual CPARS information for non-systems services contracts.

“The awardee to those contractors who can demonstrate through a proof of concept/viable prototype that AI can help the contracting officer identify the few CPARS records related to each contractor being evaluated in a specific source selection/evaluation that are most relevant based on the solicitation and related requirements,” the solicitation states. “In this context, AI is most likely a set of autonomous or semi-autonomous system methods that will enable advanced automation, continual learning, prediction and decision aids to solve complex, dynamic problems. Additionally, in this context, AI that is human readable (humans can understand what the AI is doing and how the AI processes the data to achieve the intended results) as well as AI that is verifiable (techniques are utilized to produce objective results that can be trusted, are free from biases, and that produce intended outcomes in a repeatable and objective manner) is of utmost importance.”

Winning vendors will have to demonstrate their prototype within 120 days after receiving the award.

“An AI tool would allow contracting officers the ability to scour all offerors CPARS performance ratings to get a more accurate and balanced view of the contractor’s performance for the type of work they’re bidding on,” GovConRx’s Smith said. “Additionally, a CPARS AI tool could allow for new acquisition strategies that may use past performance in a source selection as the primary basis to determine which contract vehicle to use, as a primary technical evaluation for ‘capability,’ or even use past performance as the primary basis for a technical evaluation, which has already occured on a limited basis, and was upheld by the Government Accountability Office. This will probably increase as AI provides contracting officers with more recent relevant and accurate CPARS data.”

The IRS also is looking at how to automate the CPARS process.

The IRS’ Webbers said the tax agency may be looking to test out ways to use technology to automate and standardize information to make better decisions.

“We are looking at it and possibly exploring how to move forward so we get speed, accuracy and consistency,” she said at the PSC event.

While AI may be useful, the real issue in fixing CPARS is comes back to language. Agencies should rethink the definition of what it means to be successful and the use of the word “satisfactory.” It has a perceived meaning — fair or not — that has negative connotations and a new approach would make CPARS more valuable for both industry and agencies.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED