Secretary’s ‘OneUSDA’ vision rings hollow to some in light of new telework policy

The Agriculture Department issued a new policy that requires employees to be in the office at least four days per week thus limiting telework to two days per pay...

Agriculture Department Secretary Sonny Perdue has laid out a new vision for his department called, OneUSDA.

“We are one family working together to serve the American people. And if we are to fulfill our mission — to make USDA the most effective, most efficient, most customer focused department in the entire federal government — we must function as one single team,” Perdue wrote to about 100,000 employees during the first week of 2018.

But Perdue’s words are ringing hollow to many USDA employees after he decided to make what some call arbitrary changes to the agency’s much admired and recognized telework program.

USDA’s new policy requires employees to be in the office four days a week, letting them telework only one day per pay period. The old policy allowed almost unlimited telework and was a key piece of the agency’s initiatives around work-life balance and reducing its real estate footprint.

For many USDA employees, the change flies in the face of creating OneUSDA, and Perdue’s focus on family and efficiency.

“USDA [is] cutting down on telework for all employees — Wow!! Talk about using a hand-grenade to remove a hang-nail,” wrote one USDA employee to Federal News Radio. “This story reeks of poor government decision process. Instead of using data and analysis to get to root causes, just hammer the entire department with severe reduction in telework, so they alienate the staff and eliminate any possible real estate savings from desk sharing or hoteling.”

Federal News Radio heard from more than a half dozen employees worried about the changes to the telework policy.

“People are complaining about suddenly, without warning, having to find pre-school and post-school baby sitters, changing (if possible) trade-off arrangements with spouses, finding car pools and the costs of commuting,” wrote another employee. “Many feel dismissed and ambushed, and are looking for jobs elsewhere.”

| USDA Fast Facts | ||||||||

| Number of employees | 97,289 | |||||||

| Number eligible for telework | 58,635 | |||||||

| Number of employees teleworking in FY 2016 | 32,356 | |||||||

| Percentage of eligible employees teleworking in FY 2016 | 55% | |||||||

| Percentage of employees teleworking in FY 2016 |

33%

|

|||||||

| Three or more days | 9,623 | |||||||

| One-to-two days | 8,243 | |||||||

| Situational | 14,490 | |||||||

Source: OPM 2016 Telework Report to Congress

While these and other employees are ringing the alarm bells, the fact is Perdue is well within his right as the secretary to make the changes to the telework policy. He is not forbidding telework, but limiting its usage. And to be clear, telework is not a right, it’s a privilege.

“The appropriateness of the amount of telework suitable for eligible employees is ultimately a determination reserved for supervisors and managers. Decisions as to frequency of telework participation is determined by the nature of the position, duties and responsibilities, supervisory relationship, and mission criteria,” the new policy states. “When telework is used to address space availability restrictions, such as in the use of hoteling or desk sharing, a mission area, agency or staff office head may approve telework exceeding 2 days a pay period on a case-by-case basis. When telework is used to ensure mission functions continue to be performed during a wide range of emergencies, including localized acts of nature, accidents, and technological or attack-related emergencies, a mission area, agency or staff office head may approve telework exceeding two days a pay period on a case-by-case basis.”

One USDA official, who requested anonymity because they didn’t get permission to speak to the press, said while they see the benefits and drawbacks of telework, Secretary Perdue initiated a major reorganization effort that the old concepts of mission and success are changing for many people.

“I can make the argument that it doesn’t matter where you work, but I also can make the argument that in-person teams matter, especially when you are reorganizing the agency,” the official said. “At times it feels like we are so accommodating that we don’t get anything done because we shy away from making a tough call because someone will not like it or not feel included. At times it feels like pendulum has gone too far where there is too much carrot and not enough stick. Maybe this is too much stick and not enough carrot, but we are being asked to increase the focus of driving mission and on customers. That is hard work. This doesn’t happen successfully in the federal government if the boss isn’t saying this is what we want to do and drives hard toward that goal. Usually in the federal government things start to fail when they get hard.”

A USDA spokesman said in an email to Federal News Radio the decision to change the telework policy comes from feedback from employees reflecting longstanding concerns about the previous policy.

“This went to mission area human capital officers and agency heads, who circulated it internally through their program staff. It was also submitted to the national unions for their comments,” the spokesman said. “USDA’s telework policy is designed to be responsible to the taxpayers and responsive to the customers who depend on our services. It is also respectful of our fellow employees who come to work each day.”

Some changes may be drastically different

The change that Perdue is leading isn’t easy and the old adage that “change is hard” definitely applies. Perdue seems to recognize that change management is necessary in his message to employees from early January.

“So every change we detail today and in the weeks and months ahead is to make us function as one single team. I will be forthright with you. Some of these changes may be drastically different than the old way of doing things, and that’s OK.” Perdue wrote to staff. “All of them point to our first strategic goal: to ensure our programs are delivered efficiently, effectively and with integrity.”

The problem for several employees and unions representing workers is the change is being done to, instead of done with, employees.

Jeff Streiffer, the immediate past secretary treasurer and spokesperson for the American Federation of Government Employees Local 1106, said the motivation behind the policy change is unclear.

“We were involved in the consultation process for local and national AFGE as well as some of the other national labor unions representatives,” he said an interview. “When USDA rolled out its draft telework rewrite to the national AFGE about 2-to-4 weeks ago, we made comments on the idea of reducing the number of telework days to four per pay period or twice a week. We advised them it was too restrictive and not warranted. We received a response that they disagreed and that’s all the response really said. So when the final revision rolled out, it was more restrictive than four days.”

Streiffer said AFGE now is investigating whether USDA violated the National Consultation Rights statute under the Federal Labor Relations Authority.

“We didn’t have notice that they were going that far with the new policy. If their intent was two days then it was a bad faith bait-and-switch,” he said.

Streiffer said he couldn’t go in to any further details about possible legal action against USDA.

Stan Painter, chairman for AFGE national joint council of food inspection locals and a USDA employee for 32 years, said the new policy is a step backward.

“There was no communication. It was like this was it take it or leave it, and it came across as a dictatorial decision and just enough to leave telework in place,” he said. “There are managers that I deal with that telework all the time and they are more responsive when they telework than when they were in the office. When they were in the office it was from this time to another time. But when they telework I could get a hold of them more easily.”

Another USDA employee who works as a reasonable accommodation coordinator, said they had heard about a month ago of a rumored change.

“Since telework can be a reasonable accommodation employees request, I heard my business was about to boom,” the employee said. “Everyone who wants more than one day a week can get it if they can come up with any disability. It’s not that hard to be qualified as someone with disability. The American with Disabilities Act 2008 amendments made it easier to qualify if you have a have medical condition that substantially limits major life activity. But substantial has been gutted so if you have back or leg impairments, that counts. So many people have bad backs or bad knees and we need to take commutes in consideration when we look at reasonable accommodation, according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.”

The employee added, whether or not someone needs reasonable accommodation, reducing the number of telework days to no more than one per week is a major disruption for a lot of people.

Award-winning telework program

The decision to reduce the number of telework days leaves current and former USDA officials confused even further considering the agency has been a model for public and private sector companies.

Forbes named USDA to its top 500 places to work in 2015, in part because of its telework policy.

“When I was at USDA, we were dealing with 16 different organizations with 3,000 different physical office space locations across the country. Our goal was to tie telework to reductions in offices that were not utilized or less utilized. USDA was trying to think strategically how to tie telework to important objectives so it will be interesting to see how they accomplish this transition,” said Mika Cross, a federal workplace expert who helped shape USDA’s workplace policies under the former administration and is now at a different agency. “The push was to empower supervisors to make decisions about their team. They should be able to determine what works for their team based on the job and mission. We really worked hard across the government not to implement a one-size-fits-all approach for telework. The goal was to empower the supervisors and leaders to make decisions based on job suitability and performance, and employee suitability.”

Cross said the change in telework also will impact transit subsidies, office supplies and morale.

Additionally, USDA has saved millions of dollars over the past five years because of telework.

“In a time where the government is being asked to think and act more like a business, telework/remote and flexible work offers agencies a strategic, competitive edge on retaining and engaging top performers who we must be able to keep around in order to deliver the most important services to the American public whom we serve,” she said. “All the best private companies/organizations understand that workplace policies like telework are a win/win for both the organization and its employees.”

Streiffer said in his San Francisco office of USDA’s general counsel he’s worried that changing the telework policy could push good people out the door.

“We have highly trained and normally highly paid white-collar professionals like attorneys who trade a more lucrative private sector career to go in to public service because we believe we can have a better work-life balance,” he said. “When those are scaled back, then we lose the ability to attract and retain the type of people who can excel type of services to public.”

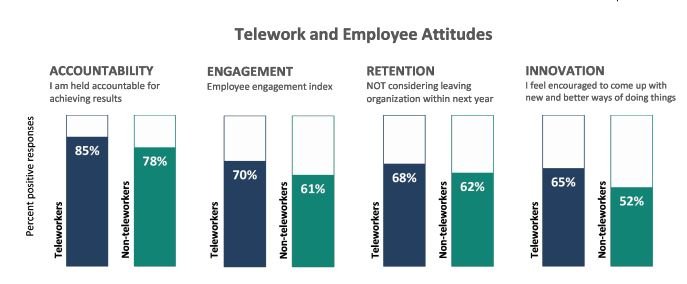

The Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey also proves out that telework is a win-win for both employees and management.

The Office of Personnel Management reported in its 2017 Telework Report to Congress that the 2016 FEVS data shows that employees felt teleworkers were held more accountable, had better engagement, retention and were encouraged to be innovative.

Others are concerned by cutting telework as a perk, its USDA and the administration’s way of reducing the workforce through attrition instead of buyouts or more harsh tactics like layoffs.

One federal official said USDA and other agencies who may want to use this tactic should be careful because many times the best people are the ones that end up leaving.

“There is a sense that change is happening to feds and not with feds. If you remember the American public and agencies were asked to give suggestions to reorganize the government, and no one ever heard back about those plans and their suggestions. Agencies never closed the feedback loop,” the official said. “With something like that you have a responsibility to close that loop. In any agency you have no idea what was put forth and what wasn’t unless you were working directly on the reorganization plans.”

AFGE’s Painter said USDA should’ve taken a more measured approach to this change.

“They should’ve run a pilot and done a study and talked about customer and workers’ satisfaction after completing a pilot,” AFGE’s Painter said. “Then they could’ve looked at what they needed to do. But that wasn’t the case. They just said this is it.”

Read more of the Reporter’s Notebook.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED