Exclusive

How a 3-year-old decision still haunts OPM’s security clearance efforts

In part two of a two-part special report, "Is splitting the security clearance process destined for failure?" Federal News Radio explains how a series of poor...

Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on iTunes or PodcastOne.

This is part two of a two-part Federal News Radio’s special report, “Is splitting the security clearance process destined for failure?” Federal News Radio explains how a series of poor decisions and mismanagement led to today’s investigative backlog.

The reason you’re waiting more than 100 days for your security clearance can be traced back to a flawed decision by the Office of Personnel Management three years ago.

On average, today it takes at least four times longer for a federal employee or contractor to obtain a clearance or reinvestigation than in 2014, leaving OPM to have to dig out of a backlog of 695,000 cases.

The decision OPM made in 2014 to drop the largest vendor performing security clearance work, United States Investigative Services (USIS), forced the agency to hemorrhage money and come within six weeks of not being able to pay its federal investigators, said Merton Miller, the former deputy director of the National Background Investigations Bureau (NBIB) and former associate director of OPM’s Federal Investigative Services.

The repercussions of those decisions are reverberating through OPM and NBIB, and they’re prompting Congress to send the majority of the security clearance workload back to the Defense Department.

Members of industry and former government officials, however, are concerned by the decision to transfer because of DoD’s own history of security clearance mismanagement. The Pentagon built its own logjam 15 years ago, the last time it owned the background investigations process.

OPM’s downward spiral

In 2014, OPM dropped the government’s number-one provider for background checks, USIS. And the agency made the decision to get rid of USIS without a contingency plan to deal with losing the government’s biggest background investigation workhorse, Miller said.

That decision and lack of planning made wait times for security clearances skyrocket from 35 days in 2014 to 158 days for initial investigations in 2017. Top-secret clearance investigations went from 75 days to 323 days in 2017, and secret clearance investigations jumped from 30 days to 132 days. The decision also caused OPM to rapidly drain the working capital fund it uses to pay for background investigations.

| Timeliness of Background Investigations (Fastest 90 percent) | ||||||||

| Investigation Type | FY 2005 | FY 2014 | FY 2015 | FY 2016 | ||||

| All initial investigations | 145 days | 35 days | 67 days | 123 days | ||||

| Top Secret | 308 days | 75 days | 147 days | 220 days | ||||

| Secret/Confidential | 115 days | 30 days | 58 days | 108 days | ||||

| Reinvestigations | 419 days | 117 days | 197 days | 219 days | ||||

(Source: Federal Investigative Services FY 2012 Annual report, OPM 2016 Agency Financial Report)

“When the decision was made by [former OPM] Director [Katherine] Archuleta not to execute the option on the USIS contract, she was briefed and her political staff was briefed on what the downstream implications of that decision would be,” Miller told Federal News Radio. “One was there would be a backlog because we wouldn’t have the manpower to support the government’s program. There’d be an increase in cost and, in fact, the decision was a $100-million decision because our other contractors, which were much smaller, charged more for the work to be done.”

A brief Miller gave to OPM projected the governmentwide investigation backlog would grow to 800,000. The backlog is currently at 695,000, according to an OPM spokesman.

The brief stated the length of time between reinvestigations would grow exponentially and that continuous evaluation technologies would not be mature enough to fill the void left by USIS. It also said OPM would no longer meet the 40-day expectation set by Congress in the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act to do an investigation.

The brief outlined detrimental cost effects as well. It warned OPM that it would lose $20 million a month, and that it would have to increase prices for its customers — other government agencies.

All of these warnings culminated, especially in 2015.

During that year, OPM investigative service was so cash-strapped that it came within about six weeks of not being able to pay its employees, Miller said. The Office of Management and Budget responded by approving a retroactive price increase to all of OPM’s customers at the end of fiscal 2015. OPM ended up billing the Defense Department about $95 million to help cover their costs.

Retroactive bills can be harmful to agencies because their money is already obligated for the year.

Hands down, 2015 was a rough year for OPM after it canceled the USIS contract.

“Seventy-five percent of the backlog grew in 2015, while the government twiddled its fingers and delayed making a rational decision about the cost of the program,” Miller said. “They absolutely saw it coming. … When the federal government in the late ’90s privatized background investigations, they built an incredible dependence on industry for background investigations to be conducted.”

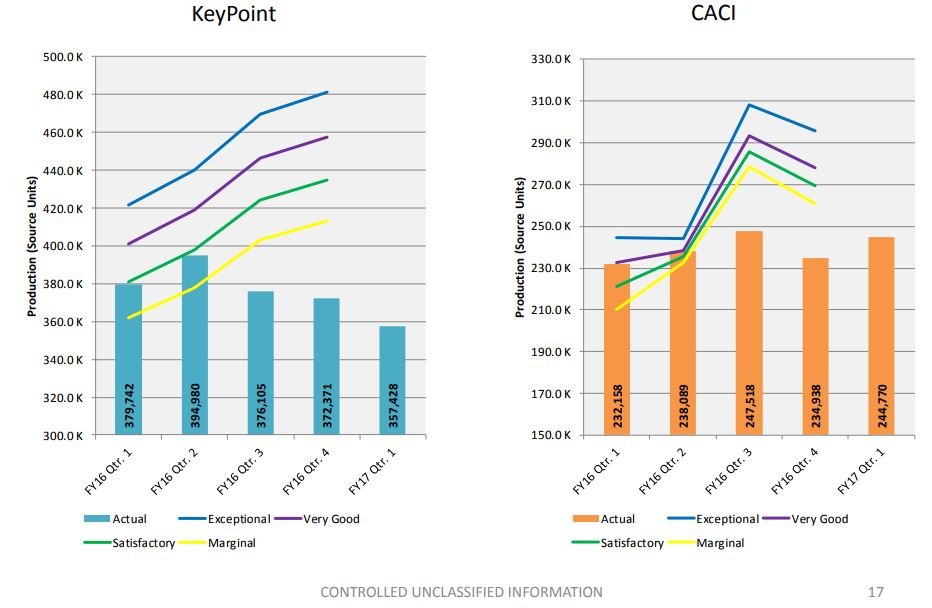

The number of companies conducting background investigations is extremely limited. Besides USIS, only KeyPoint and CACI performed employee suitability checks.

“A couple of our contractors just refused to grow; they wanted to be a niche industry, they wanted to stay the same size they were. They didn’t want the risk to their business, so they decided they wanted to stay small. USIS carried the preponderance, 60-to-65 percent of our man hours in the contract world,” Miller said.

Without USIS, in 2016, KeyPoint and CACI couldn’t keep up with the demand for processing investigations.

USIS was not without issues, however.

Miller said OPM found evidence of fraud in 2011 and began rectifying the issue.

Despite the fraud issues, OPM rehired USIS in 2011 and renewed its contract in 2012.

In January 2014, the Department of Justice filed a civil complaint against USIS. DoJ said the company submitted at least 665,000 background investigations to OPM that hadn’t been properly reviewed.

USIS eventually settled a criminal investigation with the government for $30 million, after a whistleblower stated the company’s leadership devised a scheme to circumvent quality reviews of background checks to increase profits.

Graphic by David Thornton/Federal News Radio

Again, OPM renewed its contract with USIS in 2013. But, for some reason, Miller said was not known to him, OPM did not renew the contract in 2014.

“There were 42 people that we removed from the contract. The entire USIS leadership had been changed [after the allegations of fraud]. We exercised the option on that contract not once, but twice after the fraud had been identified. The real question you have to ask yourself is, when you have brand-new leadership at USIS, the removal of the bad actors who were involved in the fraud — it was basically a clean company — why would you then not execute the option for USIS the third time?” Miller said. “I, as the associate director of that program, cannot tell you the rationale behind that, especially with the downstream implications.”

Since OPM canceled the contract, the security clearance backlog has continued to rise. Congress now wants to give DoD the power to conduct its own security clearances, something it did 15 years ago. But the Pentagon’s record with security clearances was far from spotless.

DoD’s tenure

From Miller’s perspective, DoD stymied OPM’s efforts to devote more funding and resources to the security clearance backlog.

“DoD contributed to the problem we’re having today with the backlog,” he said.

When OPM — faced with the loss of its major contractor and the aftermath of two significant cyber breaches — came within six weeks of not having enough resources to pay its federal investigators, Miller said he suggested a new surge contract that would have authorized more man-hours to help the agency process new and existing investigative work.

“We also wanted to hire 400 new federal employees, and DoD refused to help provide the financing to do that,” he said. “We had to slow-roll our hiring, and we had to onboard fewer people, because we wouldn’t have the resources or the funding to be able to pay the full salaries of 400 new agents.”

Instead, OPM decided to raise security clearance prices for its clients. Under the agency’s current revolving fund model, OPM and NBIB charge their client agencies pre-determined fees for each security clearance level. OPM typically sets those prices every year.

“It was the only way to drive DoD to actually pay the money necessary to make the investigations be conducted,” Miller said. “When [DoD] managed it themselves, [it] always tried to cut corners, stopped running [periodic reinvestigations], [it] under-resourced the Defense Security Service and [it] tried to find other ways to manage the program.”

DoD in July 2015 sent a reprogramming request to Congress to help the department cover $132 million in costs for identity protection services for its own personnel impacted by OPM’s cyber breaches and for higher-priced background investigations.

Miller, who also spent nearly two decades in the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, witnessed challenges in regard to DoD’s management of the program firsthand. According to Miller, DoD also lacked the drive to improve the security clearance process when it owned the program in the mid-1990s.

“They never resourced the program appropriately to the level of effort, the number of investigations that they were conducting year in and year out,” he said.

When resources became tight, DoD would limit the number of background investigations it conducted. Miller said the department also temporarily delayed periodic reinvestigations and instead let them sit for longer than the customary five-to-10 year review time.

The Government Accountability Office also took issue with DoD’s approach to the personnel security clearance program, which it owned until 2005.

GAO put the security clearance process on its High-Risk List in 2005, though it said it had been documenting problems with the DoD’s program since at least the 1990s. The department declared its background investigations process a “systemic weakness” since 2000.

DoD said it couldn’t estimate the size of its backlog, according to GAO’s 2005 report, but it identified more than 350,000 clearances at DoD that exceeded established timeframes for determining eligibility.

In 2005, just as DoD was beginning to transfer background investigations to OPM, neither agency met congressional timeliness standards. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 required agencies to process 80 percent of security clearances within an average of 90 days, and then the next 90 percent of cases within an average of 40 days by 2009.

Yet the challenges GAO uncovered with DoD’s security clearance program mirror OPM’s own struggles with the investigative workload today.

“DoD has taken steps — such as hiring more adjudicators and authorizing overtime for adjudicative staff — to address the backlog, but a significant shortage of trained federal and private-sector investigative personnel presents a major obstacle to timely completion of cases,” auditors said. “Other impediments to eliminating the backlog include the absence of an integrated, comprehensive management plan for addressing a wide variety of problems identified by GAO and others.”

Like DoD in 2005, OPM and NBIB continue to struggle to hire enough investigators to process more investigations more quickly.

Transferring 75 percent of the current clearance workload to DoD will make it even more difficult for OPM to hire new investigators, as both agencies will compete for the same talent in an already crowded and competitive market.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED