While the intent of the Hatch Act provisions restricting federal workers may be sound, the result is, in effect, muzzling many federal workers and depriving them of...

This column was originally published on Jeff Neal’s blog, ChiefHRO.com, and was republished here with permission from the author.

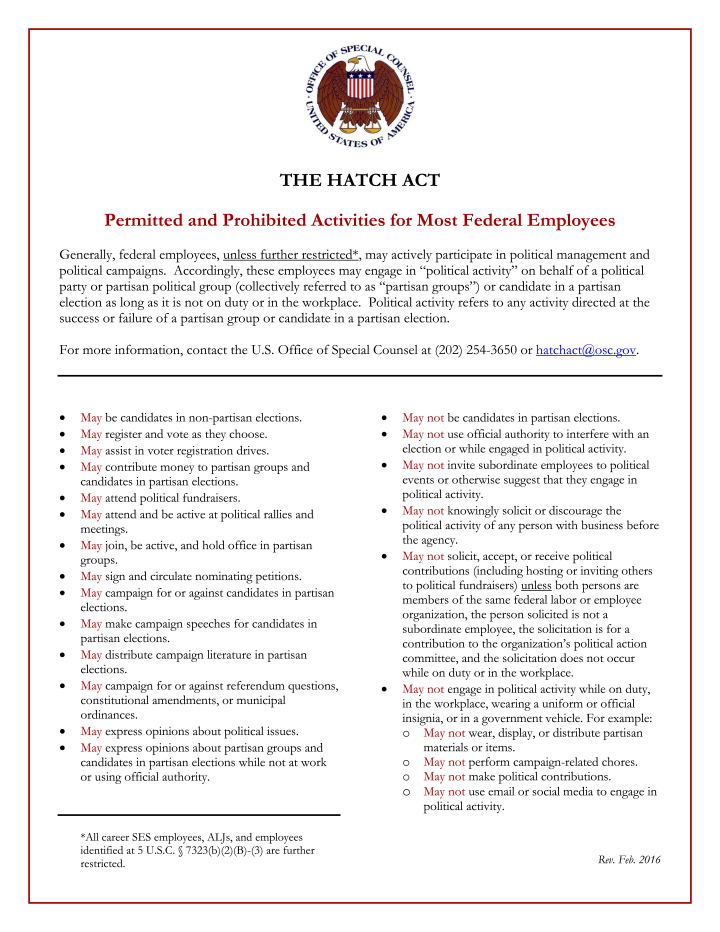

The Hatch Act, originally passed in 1939, substantially limits the political activity of most federal workers. The Supreme Court has ruled on more than one occasion that the Act is constitutional. Being constitutional does not necessarily make it the right thing to do. Here are the basic restrictions that apply to most federal workers:

And here are the restrictions that apply to “further restricted” employees — those in intelligence or enforcement agencies, Senior Executive Service, administrative law judges and other highly paid employees:

While the intent of the Hatch Act provisions restricting federal workers may be sound, the result is, in effect, muzzling many federal workers and depriving them of their First Amendment rights. Some of the restrictions as outlined Office of Special Counsel guidance border on the absurd. Consider this guidance issued to a member or the SES whose wife was considering a run for Congress. One question was, “You first ask whether you can prepare food for fundraising events held at your home.” The response? “As a further restricted employee, you may not act in concert with a candidate for partisan political office. See 5 C.F.R. § 734.402. The Hatch Act also prohibits further restricted employees from organizing, selling tickets to, promoting, or actively participating in a fundraising activity of a candidate for partisan political office. See 5 C.F.R. § 734.410(b). Therefore, because you may not provide volunteer services to a candidate, you may not prepare food for, or otherwise help organize, any fundraising event.”

So he cannot make cookies for an event in his home. OSC also noted that there is no problem with his wife holding the event in their home, but he cannot make a welcoming speech. He is able to welcome them, however.

Does that do anything to protect our democracy? I think not. Does anyone assume this gentleman would not support his wife’s candidacy? Does anyone think his direct reports or co-workers don’t know that? The Hatch Act restrictions serve to limit his right to speak and in the process reduce transparency. They also add confusion about what can and cannot be done. Many federal workers disciplined for Hatch Act violations had no intent to violate the law.

The way the Hatch Act is working now does nothing to protect our democracy, nor does it do anything to ensure electoral integrity. It prevents many employees from speaking out about the politicians whose decisions affect them, such as employees who are furloughed due to a lapse in appropriations. It drives political activity for many employees underground, and does nothing to limit the political activity of senior political appointees. When Obama Administration Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro violated the Act in April 2016, nothing happened. The OSC issued a finding that he had, in fact, violated the Hatch Act, and that was it. When Kellyanne Conway violated the Hatch Act at least twice, OSC issued a letter to President Donald Trump saying “If Ms. Conway were any other federal employee, her multiple violations of the law would almost certainly result in her removal from her federal position by the Merit Systems Protection Board.”

In both of these cases, highly ranking political appointees violated the Hatch Act and got away with it. Both spoke in their official capacity in favor of the president they served in a manner that clearly violated the law. OSC’s letter to President Donald Trump was spot on — any career employee who committed the same offense would be fired. One of the glaring weaknesses of the Hatch Act is that it is toothless with respect to an administration in power. Obama could ignore Julian Castro’s violation and Trump can ignore Kellyanne Conway’s violation.

In 1973 the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Hatch Act. In his dissent, Justice William O. Douglas strongly disagreed with the decision. Justice Douglas said, “We deal here with a First Amendment right to speak, to propose, to publish, to petition government, to assemble. Time and place are obvious limitations. Thus no one could object if employees were barred from using office time to engage in outside activities whether political or otherwise. But it is of no concern of government what an employee does in his spare time, whether religion, recreation, social work, or politics is his hobby – unless what he does impairs efficiency or other facets of the merits of his job. Some things, some activities do affect or may be thought to affect the employee’s job performance. But his political creed, like his religion, is irrelevant. In the areas of speech, like religion, it is of no concern what the employee says in private to his wife or to the public in Constitution Hall.

He continued, “If government employment were only a ‘privilege,’ then all sorts of conditions might be attached. But it is now settled that government employment may not be denied or penalized ‘on a basis that infringes [the employee’s] constitutionally protected interests-especially, his interest in freedom of speech.’ If government, as the majority stated in [United Public Workers v. Mitchell], may not condition public employment on the basis that the employee will not ‘take any active part in missionary work,’ it is difficult to see why it may condition employment on the basis that the employee not take ‘an active part … in political campaigns.’ For speech, assembly, and petition are as deeply embedded in the First Amendment as proselytizing a religious cause. Free discussion of governmental affairs is basic in our constitutional system.”

I believe Justice Douglas was right, particularly when he said, “In the areas of speech, like religion, it is of no concern what the employee says in private to his wife or to the public in Constitution Hall.” What we have is a law that restricts speech of federal workers, but in practice does not restrict the speech of highly visible senior political appointees. It limits transparency by driving political activity underground, where it is less likely to be known to anyone. I prefer transparency, and free exercise of the First Amendment rights of everyone, whether s/he works for the federal government or for Burger King. But, at least we can take comfort in knowing that senior executives will not be baking cookies for their spouse’s political campaigns.

Jeff Neal authors the blog ChiefHRO.com and was previously the chief human capital officer at the Department of Homeland Security and the chief human resources officer at the Defense Logistics Agency.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.