GSA missing target on firearm donation program

Members of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform criticized the General Services Administration for its inability to accurately track the inventory...

How did two grenade launchers end up for sale in Florida and Colorado? Who is responsible for trading five Uzis to a gun show? Is the federal agency that handles office supplies orders also qualified to run a firearms donation program?

The General Services Administration’s Surplus Firearm Donation Program came under fire March 2 from members of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, who took turns questioning and criticizing the agency for its inability to keep an accurate inventory and status of the firearms within the program.

Oversight Ranking Member Mark Meadows (R-N.C.) called the GSA’s tracking system “haphazard,” “digitally ancient,” and “half-accurate,” and asked how in the past 15 years, nearly 500 firearms went missing and only 25 were ever found.

“Among those firearms that went missing were a set of 130 handguns, five Uzi submachine guns and a pair of grenade launchers,” Meadows said. “In each of these instances the firearms were sold to private gun shops, which are not allowed under the program and appear to have never been recovered. In fact the GSA IG discovered yesterday that two of the missing grenade launchers were located in Florida and Colorado and available for sale to the general public. In some cases the firearms would go missing for as long as a decade … before anyone realized the firearms were not where they were supposed to be. It is beyond unacceptable that these firearms were lost, let alone the fact that they were not recovered and in some cases were missing for years before anyone knew about it.”

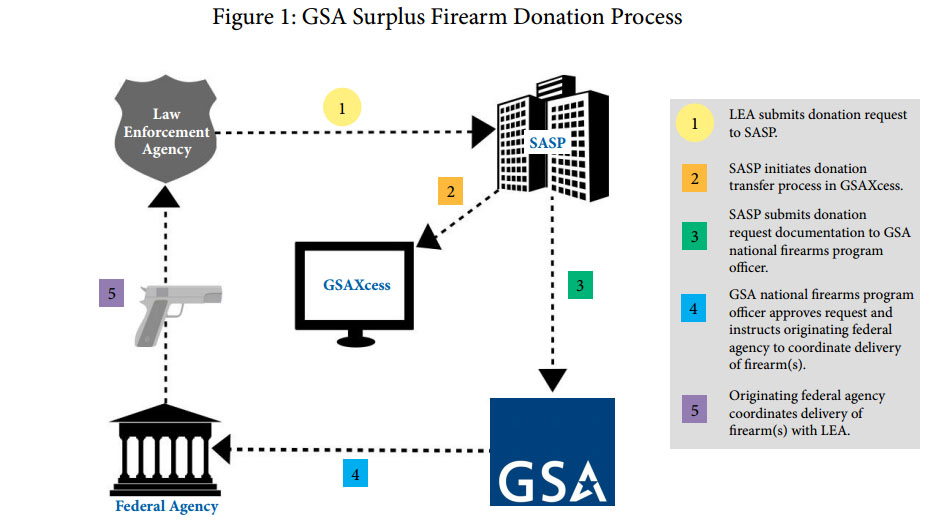

The surplus program started in 1999 as a way to make excess firearms available for use at state and local law enforcement agencies, if a federal agency no longer needed them. The GSA’s Office of Inspector General released a report in June detailing the program’s gaps and disconnects.

The investigation was conducted in October 2014. Notably, among the findings of the OIG was that donation records were “incomplete, inconsistent, and difficult to access. As a result, we were unable to independently verify critical data such as recipient name and address, and the make, model and serial number of donated firearms; therefore, we could not achieve all evaluation objectives.”

Auditors reported that the program officer kept paper copies of approval forms and documents, and spreadsheets used to track the status of donated firearms were deemed “disorganized and inconsistent.”

The IG made four recommendations, including the implementation of a better data management system. William Sisk, acting assistant commissioner for GSA’s Office of General Supplies and Services, said in his testimony that the agency agreed with the IG’s findings and was about halfway through a Corrective Action Plan — with a goal of completing all 12 steps of the plan by the end of May.

Among the steps GSA has taken to improve the program:

- Created new data fields in GSAXcess to collect more complete information on the recipients of the donated firearms.

- Issued a Standard Operating Procedure outlining procedures for requesting and processing donations, inventory and compliance, disposal and destruction, and internal controls.

- Issued guidance to the State Agencies for Surplus Property on how to conduct inventories to help assist law enforcement agencies with their obligation to account for all donated firearms.

- GSA is a member of the Federal Support for Local Law Enforcement Equipment Acquisition Working Group, which addresses ways for the federal government to standardize and harmonize programs that provide equipment and support to law enforcement agencies.

- The working group released recommendations in a report in May 2015. In line with the working group’s recommendations, GSA has ceased donations of any items on the “prohibited list,” which includes grenade launchers.

- GSA also issued policy guidance on the working group recommendations for requests and donations of controlled and prohibited equipment to its regional offices and SASPs on September 22, 2015.”

Sisk also mentioned that GSA was considering limiting the donation program to handguns and lifting Perpetual Restrictions, which means that the full title for the firearm would be transferred to the law enforcement agency taking the gun — this would occur after the statutory required 12 month period of use.

The suggestion raised the eyebrows of some committee members, including Meadows.

“This is not a complicated problem, this is not rocket science,” Meadows said. “But what it sounds like is you’re about to change your program because you won’t fix the reporting.”

Sisk said the options were not final, and his office would continue to work with the IG and Office of Governmentwide Policy to review next steps.

“We’re fixing the problems that are there with the inventory process,” Sisk said. ”We absolutely agree with you: the process, it had its shortcomings. And we’re fixing that. We are exploring different options on how to improve the process going forward. None of these decisions are final.”

Sisk also pointed out that of the “missing” firearms, about 66 percent of them were not missing, but had been sold or traded by a law enforcement agency — which is not allowed under GSA’s program requirements.

“In most instances, where the firearm is not under federal government restrictions, the disposal of the firearm, in and of itself, is not inappropriate, such as trade-in to a firearms manufacturer or sale to a licensed dealer,” Sisk said.

Oversight Ranking Member Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) asked whether or not the program’s purpose was worth the effort — only 73 firearms were donated in 2015 — and should the surplus firearms simply be destroyed.

“You can’t argue that it makes an appreciably significant impact on local government with the number 73,” Connolly said. “There’s no substantive analysis or set of vigorous criteria that guide this program, and that, when it’s tainted at the very beginning of the program, no wonder we’ve got problems at the end of the program.”

In her line of questioning, Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.) learned that GSA does not obtain physical custody of the firearms but maintains the inventory of the firearms.

Asked by Norton whether he felt GSA was the appropriate agency for this kind of mission, Sisk said GSA “[doesn’t] really have a level of expertise in firearms themselves.”

“May I suggest that is part of the problem,” Norton said.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.