Sequestration would put Army in ‘very bad place’

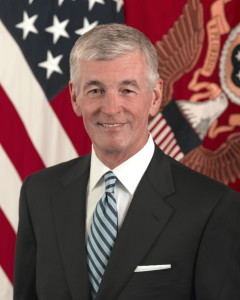

Secretary John McHugh said an impending budget showdown coupled with a reduction in forces could have a serious impact on the Army's readiness.

The Secretary of the Army, John McHugh, is concerned Capitol Hill’s sequester showdown could do more than just trim fat from the service’s bottom line — it might cut an artery.

McHugh, who spoke at the American Enterprise Institute on Sept. 15, called the impending fiscal deadline a “critical turning point” for the Army.

“If sequestration returns, any meaningful budget reduction in addition to that which we’re trying to manage right now, or that next unforeseen thing of any dimension comes forward, we’re in a very, very bad place,” McHugh warned. “I’ve testified, should either of those occur, let alone both, somebody’s going to ask us, tell us to stop doing something. Frankly as I look at the world right now, I’m not sure what that would be. This is a critical turning point for the Army, for the Department of Defense and obviously, logically, for the nation.”

Workforce reduction and soldier engagement

McHugh, who was confirmed in 2009, predicted the Army will reduce its civilian employee workforce to about 233,000 people — down about 50,000 from the current 285,000 estimate — by the end of 2018 as part of its workforce reshaping. The reduction is in response to the Secretary of Defense’s order for a 20 percent reduction and recently Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work increased that goal by five more percent for a total of 25 percent reduction.

“The Army has taken on the civilian workforce reduction very aggressively,” McHugh said. “At the height of the civilian workforce, in this era of two conflicts of war, it was about 285,000 – that growth occurred not because civilians were standing around saying we want more,” it was done, he said, so that soldiers could be placed in operational positions and be replaced by those civilians.

“We can’t do what we need to do as an army, what people think about when they think of armies, without these civilians doing it,” McHugh said.

Asked about what keeps him up at night, McHugh said one of his biggest concerns for the Army’s personnel is how to keep soldiers active and engaged in their work.

McHugh said during his 26 trips to combat theaters, he always was impressed at the authority and engagement demonstrated by young lieutenants and captains.

One of the worst things leaders can do is place those soldiers in an environment and “[bore] them to death,” he said. Right now the Army has about 136,000 soldiers who are forward-stationed, forward-deployed or preparing to deploy.

“So while the world is unsettling to people like me, to our soldiers it still provides that opportunity to go out and engage and train with other nations,” he said. “But we have to begin to do better at home station training. As challenging as our funding may be, we’re maintaining our combat training center rotations. Soldiers love to get out in the field and train. And we need to focus on other things, broadening opportunities like education, partner to partnership opportunities, just trying to do everything we can to make life in uniform of interest and challenge to our soldiers. Nobody likes a war, nobody more so than a solider, but we do have to be creative in how we keep them excited about being a member of the army team.”

Collaboration and readiness

While the Army is looking internally to find improvement opportunities, McHugh said there’s also been ongoing effort to change the Army’s relationship with the private sector.

“We’ve gotta work more cooperatively with the private sector, and I think we’re making good progress there,” McHugh said. “But we offer opportunities — I’ll use cyber as an example —the private sector can’t offer.”

McHugh said the Army is faced with highly publicized challenges, as is the private sector, but the former conducts operations the private sector does not.

“Those provide the opportunity for skill set development that I think in important ways can be of considerable value to the private sector, and we can work better together to make sure both our interests are better served,” McHugh said.

Working alongside the private sector helps to strengthen and prepare the Army, and McHugh said readiness was one area where he continues to be concerned.

“We’ve tried to be smarter but our readiness continues to be a concern for me,” he said.

The Army’s metric for readiness stands at about 32 — 33 percent among its combat formations, he said.

The Army is setting aside many of its major acquisition programs for its major development programs into the 2020s. While things such as improved armor, alternative energy programs, robots and drones can help soldiers in the field today, McHugh said fielding those advances will happen later rather than sooner because of the “fiscal reality” the Army and DoD, at large, faces.

“These are absolutely critical things no matter what the enemy may look like, wherever that enemy may come from,” McHugh said. “We are consuming that readiness because of unforeseen missions,” such as those involving the Islamic State group or something like the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

McHugh said the Army’s Operating Concept also is introducing some ways to be ready for future threats. Not only does it encourage leaders to be comfortable and rational with the unknown, it also emphasizes the Joint Force.

“In today’s era you have to present multiple dilemmas to an enemy,” McHugh said. “If you’re a one-trick pony, you’ve got the best this service or that service, that’s great, but if the enemy knows you’ve only got a 100 mph fastball, at some time they’re going to figure it out and react to it. We want every branch of our service to be the best and when and if the need comes, be able to operate effectively together.”

McHugh said the Army also has learned lessons from prior acquisition attempts in the last few decades. Referencing the Decker-Wagner study — in which a panel found that since 2004, the Army pumped between $3-and-$4 billion per year into large acquisition programs that it eventually wound up cancelling — McHugh said the results helped the Army realize that it didn’t always need the very best next thing, nor should it invest too much on underdeveloped, immature technologies.

“We understood that sometimes good enough is good enough and we also recognized that the affordable way for us in the future was to build something in a fashion that incrementally from generation to generation you could add on and adapt to whatever the new realities of the day may be,” McHugh said. “In the last five years, most of our developmental programs were on time and on budget. The reality we’ve had to deal with is … now the way forward depends on the money that lies ahead of us.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.