Gov’t spends 17 percent more on feds’ compensation than private sector, CBO says

Federal employees with a high school diploma or less earn 53 percent more in total compensation than their counterparts in the private sector, while federal workers...

The Congressional Budget Office’s latest findings that the federal government overall spends 17 percent more compensating its employees compared to the private sector is sparking fresh debate on a well-worn topic.

For some, the latest CBO report throws more fuel on the fire in an ongoing push for civil service reform and reemphasizes past arguments that federal employees are simply paid too much. For others, it reinforces government’s struggles to recruit and retain top talent in mission critical areas.

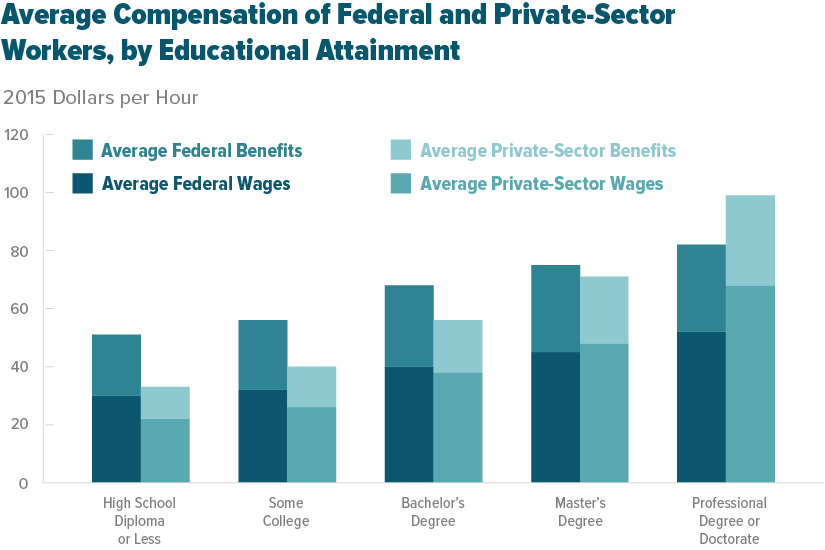

In total, federal employees with a high school diploma or less earn on average 53 percent more than their counterparts in the private sector, while federal workers with a bachelor’s degrees received 21 percent more in compensation.

In contrast, total compensation costs for employees with a professional degree or doctorate were 18 percent lower than workers in the private sector, CBO said.

“Overall, the federal government would have reduced its spending on wages by 3 percent if it had decreased the pay of its less educated employees and increased the pay of its more educated employees to match the wages of their private-sector counterparts,” the report said.

The federal defined benefit retirement package is the biggest difference between the two sectors, CBO said. Though new federal employees contribute more toward their pensions than their predecessors, defined benefit plans have become less common in the private sector.

“Higher pension contributions do reduce the federal pay advantage, but they won’t get you anywhere close to pay parity,” said Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar for the American Enterprise Institute who has studied public and private sector pay comparisons. “If you really wanted to have pay parity, you’d probably have to shift federal employees almost entirely to a defined contribution system. Just give them the TSP, which is, by itself, a very generous employer match compared to what 401(k)s get.”

Government spent about $215 billion to compensate about 2.2 million federal civilian employees in fiscal 2016. Those employees made up 1.5 percent of the U.S. workforce and are spread among more than 100 agencies and represent more than 650 occupations.

But the National Treasury Employees Union said government shouldn’t settle for pay parity, said NTEU National President Tony Reardon. They should continue to offer generous health and retirement benefits, even if the private sector isn’t.

“While many private sector employers have eliminated or slashed health insurance and retirement benefits, especially for lower-paid employees, there is no justification for the federal government to join this race to the economic bottom, he said in a statement.

House Oversight and Government Reform Chairman Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah) asked CBO to update the report, which last studied federal pay and compensation in 2012, and said the findings would inform the committee’s work on this topic in the future.

“CBO’s report underscores the urgent need for comprehensive civil service reform,” he said in an April 25 statement. “We need a system that values and rewards performance over longevity. The committee is embarking on various reforms to bring accountability and modernization to the federal civilian workforce.”

Yet the American Federation of Government Employees sees CBO’s comparison differently.

“The report is designed to justify the elimination of a pay system that does an excellent job of avoiding pay discrimination in the federal government,” AFGE National President J. David Cox said in a statement.

There have been many studies from a variety of organizations that review this topic, and some have vastly different results.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics and Office of Personnel Management annually compare federal pay with the private sector. Federal employees, on average, earn about 34.07 percent less than their counterparts in the private sector, according to their latest calculation. BLS and OPM use data from the National Compensation Survey and the Occupational Employment Statistics program to calculate their version of the pay gap between the public and private sectors. This calculation only compares pay, not the total compensation and benefits that workers receive.

The Federal Salary Council uses this comparison to calculate locality pay rates for federal employees in various locations across the country. Congress passed a law in the 1990s that was designed to eliminate the pay gap — using Salary Council calculations — between public and private sector workers, but lawmakers have never set aside enough funding to do that.

According to Cox, the BLS and OPM calculation is more accurate because it doesn’t use educational experience as the basis for making a comparison.

“The CBO approach is not useful for pay-setting, but it’s very useful for those who want to cut wages and salaries for the federal workforce,” he said.

Reardon also acknowledged CBO’s expertise in budget scoring but said BLS is the expert on wage and compensation comparisons and is the more accurate source on the topic.

Both AFGE and NTEU are members of the Federal Salary Council.

Yet Biggs said the Federal Salary Council report deploys a “faulty methodology” and produces results that are an outlier among other studies that ask similar questions.

Latest Pay & Benefits News

There are several problems with the BLS/OPM method, but grade inflation within the General Schedule is chief among those issues, Biggs said.

“There’s grade inflation in the federal government,” he said. “BLS is required to take those grade levels at face value, not analyze them themselves, but compare them to private sector, state and local jobs.”

There are also caveats in CBO’s own study.

“Those estimates do not show precisely what federal workers would earn if they were employed in a comparable position in the private sector,” CBO wrote. “The difference between what federal employees earn and what they would earn in the private sector could be larger or smaller depending on characteristics that were not included in this analysis (because such traits are not easy to measure).”

For example, the CBO study doesn’t account for the wide variety of PhDs or other professional degrees.

“You have people with PhDs in physics versus Ph.D.s in education or something like that,” Biggs said. “We don’t know whether those sub-specialties in Ph.D.s are distributed equally between the federal government and the private sector. The CBO’s data just didn’t tell them that.”

In addition, the CBO analysis doesn’t include other benefits that some workers with doctorate or professional degrees might have in the federal sector, Biggs said.

“If you are a medical doctor who works at the Veterans [Affairs] Department, you don’t pay malpractice insurance,” he said. “If you were a medical doctor on the outside, you do. If you’re an orthopedist or something like that, that’s a $100,000 you have to pay.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED