Modernization candidate: Federal payment system

If the government is in the habit of sending people money during emergencies, why not do it in time for the height of the need?

After agreeing with another couple on a house to rent for a week near a swank beach next summer, the friends went ahead and put down a deposit. How did we get them our share? A simple Venmo transfer.

Ever since grandma figured out how to attach the church bulletin faux pas collection to that new AOL email account, people have been hooked on instant transfer of whatever — pictures, knowledge, money.

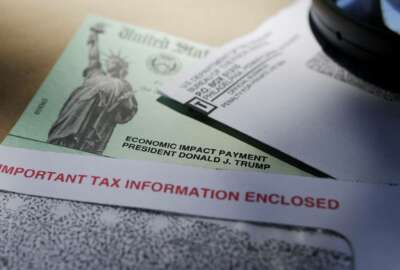

So why in 2020 did it take the government weeks to send stimulus checks to the millions eligible? That’s the question troubling Aaron Klein, a Brookings thinker and former deputy assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy. He appeared on the Federal Drive yesterday. If people really need the money immediately, why not just “wire” it to them instantaneously?

It actually does in many cases. For that matter, most recipients of recurring benefits, such as Social Security, have their money direct deposited. The IRS can do direct deposit also. Still, the pandemic relief money took three or four weeks to push out. Klein cites two reasons.

One, the perennial problem of what are known as the unbanked — people without bank accounts. You can’t direct deposit to someone’s account if they don’t have one. Two, the nation lacks a true instant payment network and instead, Klein said, relies on a financial transfer system dating to the 1960s.

As for the unbanked, there is no simple modernization plan the government can undertake. Some 6.5% of American households representing 8.5 million people lack accounts. Klein said studies show up to a third of them can’t get an account or were kicked out because they’re on a money laundering checklist or had insufficient funds. They may have run into financial problems from credit issues or identity theft. He said overdraft fees keep others out, adding, “The only people who run out of money are people who are out of money.”

There’s another socioeconomic angle on this, Klein said, in that 15% of Black and Latino households are unbanked.

Dwarfing the unbanked problem is that the government can’t simply transfer money to everyone with a bank account because it doesn’t possess everyone’s account information. There’s no simple answer to this tertiary problem, a major information, privacy and civil rights challenge.

As for the instant payment system, Klein called the U.S. system “vinyl in a world of streaming.” He wonders why the government doesn’t avail itself of the real time payment systems (RPTs) that exist here and in other countries.

The Federal Reserve System has long recognized the lack of an instant payment system, sometimes called a real time payment network. Just last month, the Federal Reserve cited the pandemic as a fresh argument for its FedNow Service, an interbank settlement service it plans to field sometime in the middle of the decade. It’s detailed in this Federal Register notice.

Reserve Board Governor Lael Brainard said in a statement, “The rapid expenditure of COVID emergency relief payments highlighted the critical importance of having a resilient instant payments infrastructure with nationwide reach, especially for households and small businesses with cash flow constraints.”

In the meantime, an organization called The Clearing House operates a real time payments network available to all FDIC-insured banks. (It adds a copyright wingding to its use of RTP.) This bank-owned group didn’t arrive just now. It dates back to 1853. You can get lost in the acronyms and mechanics of the banking and money movement systems, but The Clearing House’s RTP system looks to me like a Venmo for banks. It moves trillions a day.

Federal direct outlays, like the ones just concluded from the pandemic response, go back a ways. Recall in 2009 the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act that sent out the quaint little sum of $14 billion in stimulus checks of $250 to retirees, veterans and railroad retirees. Other Americans got tax rebates. A year earlier taxpayers received $600 from the government, plus $300 for dependent children, in a $120 billion hoped-for economic stimulus. Still earlier, in 1975, a big tax cut bill sent people 10% rebates on their 1974 taxes. About $8 billion in $100 and $50 checks went out to 55 million people.

I asked Klein if he thought the government needs its own Venmo type of system. He answered, “We have a Venmo. Why doesn’t Uncle Sam use it?” I didn’t mean Venmo specifically, or PayPal, Google Pay, Apple or Android Pay, or Zelle. But the idea of instant, secure transfer

If the government is in the habit of sending people money during emergencies, why not do it in time for the height of the need?

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

Related Stories