Like their federal brethren, state government chief information officers found themselves in an expanded role over the last few years.

Like their federal brethren, state government chief information officers found themselves in an expanded role over the last few years.

These CIOs say the biggest change, however, may be how other state agencies see the value of technology, how critical it is to the delivery of services and the productivity of state employees.

Doug Robinson, the executive director of the National Association of State CIOs, said their recent survey, which Grant Thornton and CompTIA supported, shows just how much has changed over the last few years.

“We heard across the board for many of our CIOs that, during this time period, technology became the front and center driver in a lot of states because of remote work. So the CIO role, particularly, became much more elevated. You see that in our data that the CIOs’ perception of that is that their importance and role across, across almost all of the states universally was the fact that they did have a more elevated stature. I think it’s the evolution that I’ve seen,” Robinson said on Ask the CIO. “The pandemic exposed the fact that we had the technical debt and all of these legacy platforms, many of them were on the board for modernization, but again, they’re looking at several years out. All the states were talking about improving their digital services interface, creating mass personalization, using personas, having focus groups, obviously, moving to more mobile approaches, and they’re trying to say, ‘well, how can we have a single door to all of these services?’ I think that’s what happened was during the pandemic, all of that was exposed about how difficult it is to navigate and understand how to get to these services and citizens were frustrated. That really resulted in states are trying to streamline all of their digital services.”

In the NASCIO survey, CIOs said non-technology executives realized the imperative role technology plays in delivering services and for the productivity of employees. This, again, was similar to what federal CIOs have been saying over the past two years.

“CIOs also thought their role could become even more important in the workforce conversation as remote work policies and culture begin to change,” the survey stated. “There were also a few CIOs who didn’t think the CIO role has changed as much as perspectives have changed. One CIO told us, ‘The role has not necessarily changed but we have seen that people now understand that they are much more reliant on technology than they thought they were in the past.’”

Graeme Finley, a principal with Grant Thornton public sector, said CIOs’ role, both at the federal and state levels, rose during the pandemic, in part, because they were able to deliver on what users needed. He said the coordination and collaboration with industry partners helped make that possible.

“There’s no reason why that can’t continue. It’s almost a matter of desire to do so, and not letting ourselves fall back into sort of the old ways of doing things on the old set of expectations,” Finley said. “By necessity, I think some of the traditionally more bureaucratic processes around procurement are going to put the brakes on certain types of certain larger transformations, but at a more granular scale doing things quickly, as I think something we recognize can be done will continue going forward.”

One reason CIOs said they were able to move quickly is as much the urgency of the pandemic as the tools that are now available.

The survey found 70% of the respondents using low-code, no-code platforms to improve or modernize older systems.

Robinson said in previous surveys the use of low code, no code platforms was nascent. But now it’s truly taken off.

“It was predominantly in certain agencies, not in what I would call an enterprise platform or enterprise imperative that was promoted widely by the state CIO at that enterprise level,” he said. “I think there are clearly a number of reasons why it has caught on. The speed and the ability of getting those solutions to market like vaccine registration and vaccines scheduling applications in many states were using platforms that utilized low code, no code. That would have been unheard to get those platforms up in a matter of weeks, if not months. But again, they moved with their partners to do that. The vendor partners were bringing low code, no code solutions to the state saying you’ve got this need to get this up.”

Robinson added that NASCIO issued a low code, no code policy brief last summer to help state CIOs continue to understand how to use these platforms.

Finley said the CIOs saw the benefits of low code, no code platforms and now are trying to define standards or provide enterprise capabilities that all state agencies can take advantage of as they modernize specific systems.

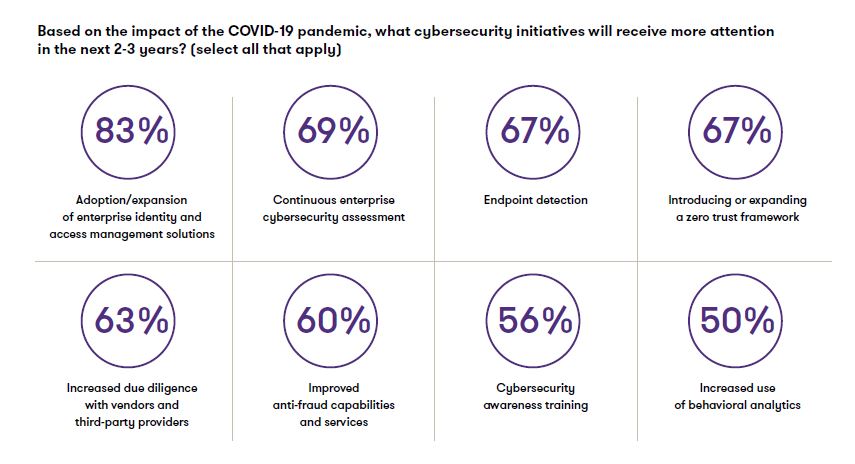

Another big change that came out in the survey responses is how states are viewing cybersecurity. The rash of cyber attacks, including ransomware that hit state and local governments harder than federal agencies, had CIOs looking different at risk management and network and data defenses.

“As one CIO noted, ‘It is important for security to be an enabler instead of an inhibitor — which is changing some of our processes and procedures.’ With the shift to an increasingly digital government and remote work here to stay, CIOs have evolved their approach to cybersecurity to further address the distributed environment and human element of cyber threats,” the survey stated. “This is evidenced in CIOs’ responses when asked to consider which cybersecurity initiatives will receive more attention in the next two to three years as a result of the impact of COVID-19.”

Finley said typically state CIOs, unlike their federal counterparts, operate primarily on a fee-for-service or a chargeback model, meaning state agencies don’t have to use the cybersecurity tools if they don’t want to pay for them.

“A lot of CIOs have been pushing to try and have more of their cyber activities funded through the general fund, and I think we’re seeing some migration toward that, or more success there, which I think is going to be good for everybody,” he said. “I think there is a recognition that regardless of whether it’s cybersecurity activities in another state agency, they will benefit you. I think that’s a positive evolution.”

Finley added, however, that money and cyber expertise on staff remain the biggest challenges for public and private sector firms.

Robinson said state CIOs struggled over the last decade to get their customers to adopt shared or enterprise cyber services like multi-factor authentication.

Now with the rash of cyber attacks and ever-growing threat of attack, CIOs are no longer saying it would be good if you adopted this cyber tool; they are more likely to mandate it.

“We do have some states that are beginning to implement zero trust, and one of the first things they’re doing is going to the human side and saying, ‘Okay, everyone that accesses the network must do this. And then we’re going to get to devices and everything else.’ So it’s just changing,” Robinson said. “Part of is getting the funding to do that because they don’t want to have extra charges, and then hear the wrath from their customers about the costs.”

Robinson said state CIOs are using all of these efforts to create a better digital experience for their citizens and customers. The survey found 74% of the respondents said that was among their biggest drivers of IT modernization.

“We saw a pretty dramatic rise in the use of chatbots and virtual agents on websites. We had done another survey in 2019 that found less than a quarter of the states indicated they were using chatbots at all. That was something that was, quite frankly, resisted by many state agencies because they felt it was too impersonal, even though it’s been used in the private sector for years. They didn’t like the fact that citizens might be interacting with a virtual agent on their website,” he said. “It’s amazing how quickly they switch because then we went from quarter to almost 80% of our respondents said they were deploying chatbots. They saw that as part of that improving digital experience because we can’t conduct your transaction right away but we can answer a lot of questions. The pandemic simply exposed, both the immaturity but also the fragility of all of these digital services.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED