‘Greatest risk we have is doing nothing:’ Trump administration details case for OPM reorg

The Trump administration has announced more details behind its proposed reorganization of the Office of Personnel Management, a week before the plan is scheduled to...

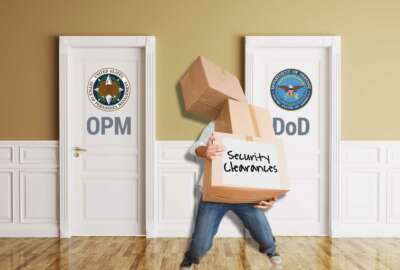

The Office of Personnel Management will face a $70 million funding gap when the National Background Investigations Bureau and its security clearance business leave the agency for the Pentagon in the coming months.

It’s one of several reasons the Trump administration is giving for its proposed reorganization of OPM, the details of which are scheduled for more intense scrutiny at a hearing next Tuesday before the House Oversight and Reform Government Operations Subcommittee.

The administration is planning to send a legislative proposal for the OPM reorg to Congress in the coming days. The proposal will detail a legislative transfer of OPM’s existing authorities to a new “service” or “entity” that will perform the kind of personnel policy the agency performs today, but within the General Services Administration.

It already released a “case for change,” which the administration also provided to the press Tuesday, to good government groups and lawmakers. Part of the administration’s “case for change” addresses the financial consequences that OPM will face if the agency continues to exist in its current form without the background investigations business.

The security clearance transfer, which the President official with a recent executive order, “will dramatically undercut OPM’s ability to operate and maintain the systems that support the federal civilian workforce, greatly increasing the risk of another failure on a scale as large as or larger than the data breach,” the administration wrote.

NBIB and the governmentwide security clearance business generate $1.3 billion, or 80% percent of OPM’s revolving fund, in revenue for the agency. Without that revenue, OPM won’t have enough funding — at least $70 million annually — to successfully continue the agency’s other functions, which include health and retirement services and personnel and workforce policy development.

OPM itself quietly warned of the consequences it would face when Congress considered transferring the defense security clearance business to the Pentagon back in November 2017, as Federal News Network first reported. But those concerns were never publicly raised, and Congress moved forward with transfer. Now, the entire security clearance business will move to DoD by Oct. 1, and the financial consequences are greater.

“I am hopeful, if not optimistic, that Congress will engage with us on finding solutions here,” Margaret Weichert, OPM’s acting director and the deputy director for management at the Office of Management and Budget, told reporters Tuesday. “Because at the end of the day, we can’t fail to deliver here. The choices we’d be left with, if we don’t have the synergies with GSA on things like overhead … [and] shared services, what’s going to get squeezed are the missions that people care a lot about.”

Those missions, which handle policy on the Senior Executive Service, employee recognition, performance management and other topics, would be a skeleton of what they are today. The IT systems that support those activities would function, but at a bare minimum, Weichert said.

In other words, OPM has few other options but reorganization, according to the administration.

“The greatest risk we have here is doing nothing,” Weichert said. “I have been very vocal in saying that while this proposal may not be perfect, it’s the one on the table.”

Weichert said she’s asked members of Congress and good government groups to develop alternatives to the OPM reorganization proposal and ideas to address the agency’s IT, financial and operational challenges and mission shortfalls.

“I’m disappointed to say I haven’t heard other ideas,” she said. “I am open to them.”

OPM does receive annual appropriations, about $265 million, from Congress. Weichert dismissed the idea that Congress could simply appropriate more funding to modernize OPM’s IT systems.

“The challenge that we have is … the way IT has been structured at OPM,” she said. “Only about $100 [milllion] of the $450 million of the annual IT spend is directly under the centralized control of the CIO. Most of the spend is represented in contracts that are directly leveraged by the program offices and [are] very hard to manage in an integrated fashion. We don’t have a fundamental shared services IT model that many, including those who instituted the FITARA scorecard, believe is the path forward.”

GSA, by contrast, has that structure, Weichert said.

According to the administration’s case for change, the OPM reorganization is expected to realize $11-$37 million in cost savings a year. Weichert said most of those cost savings would come through consolidating contracts and facilities.

“We don’t anticipate leaving this building,” Weichert said of OPM’s headquarters in Washington. “We do believe that there are different space allocations within this building that should free space for others in government to utilize, thereby lowering our overall overhead.”

Strategic, operational and IT challenges hinder OPM mission

Beyond OPM’s current financial challenges, Weichert said IT and operational issues also exist, which she’s become more attuned to since becoming the agency’s acting director last October.

OPM’s IT challenges, particularly the agency’s response to the 2015 data breaches and a backlog of pending security clearances, have been well-documented. NBIB, however, has made significant progress in whittling down an inventory that reached a record-high of 725,000 investigative matters in April 2017. The inventory now sits at roughly 459,000, according to NBIB Director Charlie Phalen.

But the administration’s case for change also references legacy IT systems that date back to the 1980s. OPM itself has made multiple attempts to shorten and improve the process for handling federal retirement claims.

“Throwing more money at the problem doesn’t fundamentally fix how we get after creating shared services support structures and moves to leading practices around case management and around high-tough, continuous improvement,” Weichert said of OPM’s antiquated systems. “[Those] are all things that GSA has experience and proven capabilities in moving toward.”

Those IT challenges have distracted OPM from performing what civil service reformers perhaps once envisioned when they formed the agency back in 1978 — a central personnel entity that oversees all federal employees.

OPM and its employees today are focused more on administering Title 5, Weichert said. The agency doesn’t have universal authority over policies that govern, for example, Title 10 or Title 30 employees, and they don’t have the ability to predict and chart a path forward for a more modern workforce.

“What’s the workforce of the 21st century need to look like? There is no one in OPM today who is able to do that for all of government,” Weichert said.

Instead, agencies have developed their own alternative systems in search for a way out from the constraints of a decades-old personnel system, she said. Weichert envisions a future where a centralized human capital office manages personnel authorities for all employees across government, but OPM as it’s structured today can’t handle additional workload, she said.

“Frankly today, OPM can’t take on anything else, because we have operational backlogs,” Weichert added. “We have IT challenges. We have real challenges doing what we’re tasked with today. Ultimately, it would make sense to have a more unified approach to all of government from a delivery standpoint, but we’re not there yet.”

Most of OPM’s existing functions would transfer to GSA if the Trump administration gets its way. The reorg proposal also suggests adding three additional people to OMB’s existing Office of Performance and Policy. The office would be modeled after OMB’s Office of Federal Procurement Policy.

Situating this office within the Executive Office of the President would elevate the federal human capital management mission, Weichert said.

Administration pursuing other options for reorganization

Under the upcoming legislative proposal, the administration will ask for the authority to lift and shift OPM’s current employees to GSA.

Weichert said all OPM employees who work on personnel policy today will move to GSA under another “service,’ similar to the organization of the Federal Acquisition Service, for example.

OPM’s existing employees who handle health for 8 million beneficiaries and retirement services for some 5 million annuitants would also likely move to this new “service” under GSA.

“We fundamentally believe that the people of OPM have done absolutely the best they can in a structure that is not well-aligned to the 21st century demands,” Weichert said. “This isn’t a matter of people failing to do a good job. They have done the best with a structure that is outmoded.”

But the administration is also considering other avenues to pursue OPM reorganization.

The administration will explore using inter-agency agreements to hire GSA to support OPM’s existing IT capabilities, Weichert said.

In addition, the administration is reviewing whether it can delegate specific activities to GSA, Weichert said. GSA could, for example, manage OPM’s existing headquarters in downtown Washington, D.C.

Finally, the administration is considering whether it can use Title 40 authorities within the U.S. Code as the legal authority to move OPM’s IT systems to GSA. A section in Title 40 allows the Office of Management and Budget to review and take action if it believes an agency isn’t managing its IT properly. Outsourcing OPM activities and better leveraging both agencies’ fee-for-service operations are also possibilities, Weichert said.

The administration reiterated it doesn’t envision OPM employees would lose their jobs during the reorganization, though Weichert acknowledged attrition may be natural.

She said she’s spoken with federal employee groups and the American Federation of Government Employees, which has a bargaining unit at OPM.

The administration needs to keep employee groups informed, Weichert said, so it can continue to build trust with the federal workforce and build an appetite for broader, more ambitious civil service changes.

“We need to be pro-employee throughout [this] change, or we will not get another at-bat,” she said. “When we say we are not looking to downsize the workforce through these changes, we mean it. That gives us the right to continue to find solutions to these systemic structural problems.”

Yet AFGE on Tuesday reiterated its opposition to the proposed OPM reorganization.

“This administration is clearly following a ‘ready, shoot, aim’ strategy built on misleading everyone about its motivations,” AFGE National President J. David Cox said in a statement. “Congress must prevent this reckless move in order to protection OPM the institution from this irresponsible plan.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED