Exclusive

Why OPM is warning against DoD reclaiming the security clearance process

In a special report, "Is splitting the security clearance process destined for failure?" Federal News Radio explores how a small provision in the 2018 defense...

Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on iTunes or PodcastOne.

When a backlog of pending security clearances piles up too high, Congress has one answer: Hand it to someone else.

That’s what lawmakers did in 2004, when the Defense Department had its own immense inventory of background investigations, and lawmakers, frustrated with DoD’s delays in processing them, called on the Office of Personnel Management to serve as the governmentwide security clearance provider.

Now, as the backlog, once again reaches new extremes, Congress is taking a page out of its own history book and is sending the security clearance process back to the Pentagon.

Lawmakers included a provision in the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act that would give DoD complete ownership over the security clearance process for its own personnel.

The House and Senate already passed their versions of the authorization bill and reconciled the bill in conference. The House will vote today on the final version. It’s unclear when the Senate will vote on the conference report.

When the authorization bill reaches the president’s desk, the Office of Personnel Management and the National Background Investigations Bureau (NBIB) will concede 75 percent of its current workload to DoD — along with several thousand federal and contract investigators, more than 100 NBIB staff and at least $1 billion in fees that the agency currently collects under its revolving fund.

House and Senate Armed Services Committee members cited a seemingly insurmountable backlog of 700,000 pending clearances at NBIB and a subsequent threat to national security as the main reasons for the transfer.

But according to both OPM and NBIB’s reviews of DoD’s implementation plan, which Federal News Radio obtained, the agencies fear the move could potentially add to the backlog and would undermine the one year of progress NBIB has made. The documents, which haven’t been released publicly or even broadly across the government, said the transfer also would cripple NBIB’s ability to process security clearances for the rest of government and would make a serious dent in OPM’s pool of resources and staff, both organizations said.

And in an administration that’s directed agencies to find more efficiencies, the split could potentially duplicate security clearance processes across DoD and OPM.

“The [DoD] plan conflicts with the current administration’s goal to merge redundant functions split across agencies where consolidation supports efficiency, effectiveness and accountability,” OPM wrote in its impact assessment. “[The] plan will consume significant time, attention, and personnel and financial resources due to the inevitable complications and challenges that will arise during a transition of this magnitude. Contrary to DoD’s stated plan, its time will likely be spent developing capability instead of driving reform.”

“The [DoD] plan conflicts with the current administration’s goal to merge redundant functions split across agencies where consolidation supports efficiency, effectiveness and accountability.”— OPM

Those impacts have gotten little-to-no discussion, at least publicly, and House and Senate armed services members appear to be unfazed by DoD’s past struggles with the security clearance process.

Members of industry also fear the topic hasn’t gotten enough publicity.

“There’s not a lot of public record on the transition to DoD, not only about the provision, but about the implications of it,” said Alan Chvotkin, executive vice president and counsel for the Professional Services Council, in an interview with Federal News Radio. “It’s not a simple binary decision. DoD’s own implementation plan highlights the complexity of the decision, and I don’t know the extent to which Congress has an understanding of that.”

DoD’s implementation plan

About 75 percent of security clearances are for DoD jobs. With the current backlog, it takes about six months to get a basic security clearance and almost a year to get a top-secret clearance.

The House Armed Services Committee argued the NBIB backlog threatens national security and military readiness. Members also said the long wait times will drive young, talented private-sector recruits away from the Pentagon.

In the 2017 Defense Authorization Act, Congress tasked DoD with coming up with an implementation plan where the Pentagon would own its own security clearance process.

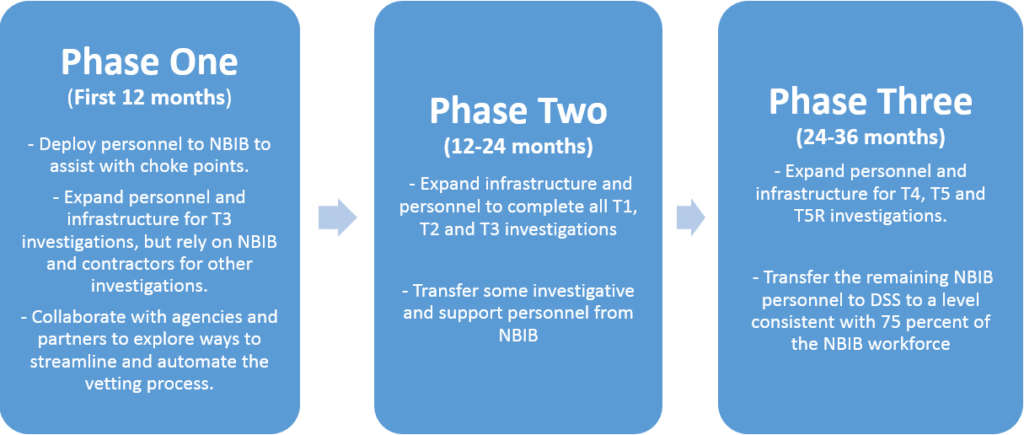

In that plan, obtained by Federal News Radio, DoD outlined a three-phased approach over three years.

“This approach would allow [the Defense Security Service (DSS)] to begin making an impact on the NBIB backlog of DoD investigations while building investigative capacity, developing automated and streamline solutions and examining transformational changes to the [background investigation] process,” the plan states. “By the end of phase three, DSS would be responsible for the end-to-end processing of all [background investigations] required for DoD-affiliated individuals.”

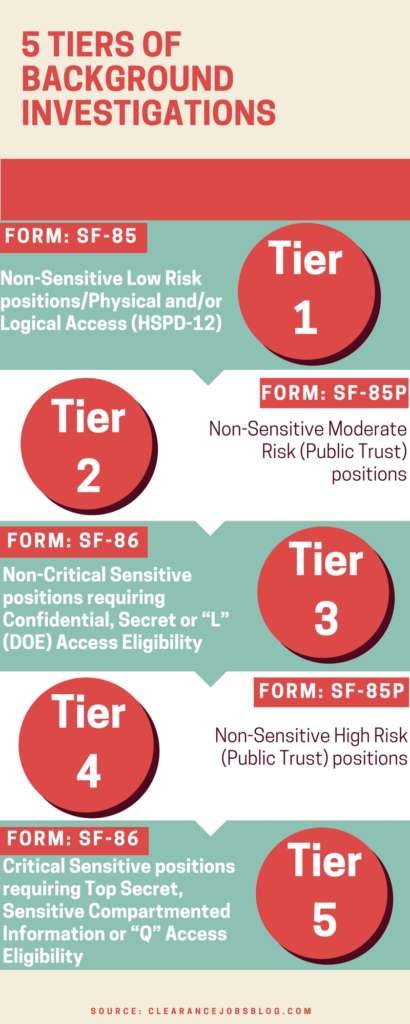

The approach would slowly take responsibility from NBIB by first performing Tier 3 clearance investigations. Those investigations are employees who need access to non-critical, sensitive information.

Over the next two years, DSS would expand its scope to take over investigations for all tiers.

DSS also would increase its facilities, IT systems and take as much as 75 percent of the personnel from NBIB over the three-year phase-in period.

In addition, the service would build an innovation team to propose “creative options for end-to-end reform” by using DoD’s contacts with Silicon Valley.

DoD also would create a digital service team to develop software around security clearance processing, use commercial solutions when needed, and leverage “cutting-edge” technology.

“DoD’s approach will be driven by innovation — investments will be made in research and innovation, artificial intelligence, DoD continuous evaluation,” the plan stated. The mission will be run “by sound leadership and governance; and well planned and coordinated mission execution.”

DoD states the plan would consolidate responsibility for submissions, investigations and adjudications by using a suite of shared services. The Pentagon claims the plan will improve the ability to control costs, better prioritize investigations and maintain active background files for upgrades, updates or other investigations.

The department will rely on continuous evaluation programs to process periodic reinvestigations more quickly and continually, rather than review existing clearance holders every five-to-10 years.

“The conversation in security clearances has really changed, compared to when the Office of Personnel Management was first given authority over the security clearance process,” said Beth McGrath, former DoD deputy chief management officer, and now managing director at Deloitte Consulting. “It’s insider threats, counterintelligence and how do personnel security and access to classified inform each other. We just didn’t have that. That wasn’t part of the conversation.”

Now every device collects data on a person, which can be used to ensure an employee is who they really claim to be.

PSC’s Chvotkin praised DoD’s plan for taking bold steps in using continuous evaluation (CE) more often. CE is something that should be adopted no matter who has control of the process, he said.

But continuous evaluation itself is still a relatively new program.

“There’s a lot more that they need to know in order to achieve the benefits and the outcomes of continuous evaluation, and we’re not there yet,” Chvotkin said. “So building a plan that says continuous evaluation is my solution — when it’s still in its early stages — worries me. The use of continuous evaluation does not, but the expectation that it can deliver more than its current capability, I don’t see a pathway to enhancing that.”

Continuous evaluation can help investigators track and report some, but not all, suitability elements.

“While technology is really good at identifying things like criminal history and credit history, there aren’t any databases out there that can help you identify a person’s mental health status,” said Charlie Sowell, chief operating officer for iWorks Corporation, and former senior adviser to the Director of National Intelligence. “If there were any questions about someone’s mental health or loyalty to the United States, those are things that get to be really difficult for a system to assess.”

DoD’s overall plan is getting mixed reviews from industry.

The National Defense Industrial Association applauded DoD’s takeover of the process.

“In doing the background investigations, the Pentagon will speed the process and get these important new personnel where they are needed as soon as possible,” NDIA President and CEO Hawk Carlisle said in a statement. “We support the Pentagon’s plan to take this on.”

Four other defense industry organizations, including the Aerospace Industries Association and the IT Alliance for Public Sector, were not as optimistic.

The plan “will create a parallel process and duplicative regime in the department that will drain resources, cause further delays, hinder process improvements and undermine efforts to move the government toward true reciprocity across all departments and agencies,” the organizations wrote in a Sept. 29 letter to the House Armed Services Committee.

Not only do some doubt the results of the plan, but Merton Miller, the former deputy director of NBIB, and former associate director for OPM’s Federal Investigative Services, said the transition would be messy and take too much time.

“That’s three more years of doubt that the federal government is going to be experiencing within the background investigative program. If I was working as the deputy director of NBIB now and I’m onboarding resources, knowing that DoD is going to take over in three years, I’m going to focus on the other [non-DoD clearances.] I’m going to focus on the customers I’m going to have long-term … You can’t take three years to effectively transition this program. You can, but it won’t be done the right way,” Miller said. “Three years is a long time. When has any plan lasted three years and been done right? The contractors are going to be in doubt as to who they are going to be working for in the future. Are they going to throw all their eggs in the DoD basket? Are they going to shortchange OPM on the resources they need?”

“The contractors are going to be in doubt as to who they are going to be working for in the future. Are they going to throw all their eggs in the DoD basket? Are they going to shortchange OPM on the resources they need?” — Merton Miller, former NBIB deputy director

DoD even admits there are serious risks to its plan. Officials added a risk register to its plan, which rates the impact and likelihood of risks in taking control of the security clearance process.

In the main text of the plan, DoD states it is unable to come up with an estimate for the cost of the transition. On the other hand, the risk register states startup costs $75 million to $100 million “taking funds away from other critical department objectives.”

The register rates the impact from one to five, with five being the most significant; and from one to five in likelihood, with five being highly likely.

DoD rated the cost likelihood a five, and the impact a three. DoD states it will mitigate those impacts by recapturing overhead costs currently paid to OPM and will reinvest that money in background investigation infrastructure.

As for the 700,000 clearance backlog, DoD estimated 87 percent of it is for DoD personnel, civilians and contractors. In the plan, DoD valued its security clearances at $1.29 billion and will require 5.9 million hours of work to complete. The likelihood and impact are both rated at five.

The risk register notes the transition may impact contract providers, and that they may experience increased turmoil, which will increase the amount of work. DoD rated the impact and likelihood as a four.

DoD stated it will collaborate with the General Services Administration, the DoD acquisition office and the Defense Contract Management Agency to develop the background investigation sector. DSS will invest in economists and other experts to develop models that will eliminate entry barriers. DoD also stated it will work with the Labor Department to provide incentives to keep a workforce of veteran background investigators.

DoD is willing to accept all of these risks just to own its security clearance process, but OPM has grave concerns about splitting the security clearance process.

OPM concerns

Both OPM and NBIB argue that DoD’s proposal is based on inaccurate assumptions about the time, budget and resources it will need to transfer defense-related clearances.

Since OPM officially stood up the NBIB roughly a year ago, the agency hired four vendors and more federal investigators to boost the security clearance agency’s workforce by 25 percent.

Monthly production is up 6 percent in fiscal 2017 for secret and top-secret clearances, and it increased another 15 percent during the last quarter of 2017, compared to the previous year’s monthly averages, according to NBIB’s assessment.

Although the contracting community has been frustrated by the time it’s taken for their employees to receive clearances, some concede NBIB is still a relatively new organization.

“Perhaps NBIB hasn’t had enough time to really see the effect of the changes that they’ve been making as they stood up that organization,” Sowell said. “It takes time to work off a backlog. It takes time to address the underlying issues that created that backlog.”

That backlog has stabilized, NBIB Director Charlie Phalen told the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee in October. The most recent estimate puts the NBIB inventory at about 695,000 pending cases, according to an OPM spokesman.

Phalen predicted it would take three years — if all four NBIB vendors maintain their work and the agency can continue to hire more federal investigators — before the backlog stabilizes at a “steady state” of about 180,000 pending clearances.

But soon under the transfer, DoD will need to recruit and hire new investigators, meaning the Defense Department and NBIB will compete for the same talent in an already scarce field of investigators.

“NBIB’s current initiative to increase investigator capacity both with new federal employees and new contractor personnel would be severely disrupted by the transition of the investigative program, therefore negatively affecting ongoing efforts by OPM to work down the current inventory,” OPM wrote in its impact assessment.

“NBIB’s current initiative … would be severely disrupted by the transition of the investigative program, therefore negatively affecting ongoing efforts by OPM to work down the current inventory.” — OPM impact assessment

DoD said it will need to hire an additional 563 full-time equivalents at headquarters to support at least 6,511 federal and contractor investigators. NBIB would transfer 146 of its staff to DoD, which OPM argues it can’t support.

“This would not be feasible for OPM, as support and scope in these functions will still be needed for OPM to serve the rest of government, especially as OPM staff will still form a number of centralized functions for the enterprise,” the agency wrote.

DoD personnel accounts for about 75 percent of all governmentwide security clearances. Subsequently, 75 percent of the NBIB workforce will transfer to DoD, the department said.

But transferring a share of the NBIB workforce that corresponds with the investigative workload is a flawed assumption, OPM said.

“The plan does not recognize that to function as separate investigative service providers, OPM and DoD will each need basic operational resources that cannot be scaled directly to investigative workload,” the agency wrote in its impact statement. “For this reason, the overall program footprint and resulting costs will increase as a result of the significant duplication of effort this plan creates. NBIB would need to retain significant resources and services that DoD would need to replicate on its own.”

OPM and NBIB are also skeptical of the cost estimate DoD included in its implementation plan. The department underestimated how much it will need to pay for its new staff, investigators and other start-up resources, OPM said.

OPM also argues DoD underestimated the costs of using NBIB’s legacy systems until both agencies fully deploy the National Background Investigations system, which the Defense Information Systems Agency signed up to build and develop when the Obama administration announced the NBIB in 2016.

Though neither the OPM assessment nor the NBIB review described the impacts in detail, the DoD transfer of 70-to-75 percent of the current investigative workload may have some crippling effects on OPM and its budget.

Miller, the former NBIB deputy director, said OPM’s footprint would be cut in half with the DoD transfer. According to OPM’s fiscal 2018 congressional budget justification, 3,180 out of the agency’s 5,876 FTEs worked for the NBIB in 2017.

OPM supports NBIB through “common services” — IT, contracting, security, general counsel and other resources — that help the investigative agency function. NBIB pays OPM a “common services fee” for those resources.

“When NBIB sends 70 percent of the work to DoD, if they lose 70 percent of their staff, OPM is only going to have that other 30 percent of NBIB to support [it] from the common services perspective,” Miller said. “The common services fees for NBIB … to OPM helps them keep afloat in a lot of areas —staffing, IT, those kinds of things.”

“I honestly do not know how they’re going to make ends meet without some additional resourcing coming from OMB, ” he added.

OPM declined to respond specifically when asked how the DoD transfer would impact its budget.

DoD’s implementation plan suggests the department plans to pay OPM some common services fees as it continues to use NBIB’s legacy IT systems during the three-year transfer. Yet some of DoD’s estimates are inaccurate, OPM said.

“The plan does not accurately calculate NBIB’s cost for common and direct services, as the $73.9 million figure outlined in the plan only accounts for the cost associated with NBIB common service and select direct services,” OPM wrote. “The plan does not account for the $112 million that NBIB funds for direct services to pay the OPM [chief information officer] to maintain and execute required modifications to the legacy [background investigation] systems.”

In addition, OPM, like some members of industry, are concerned by DoD’s three-year implementation plan.

The challenges of standing up a brand-new capability to process clearances for 75 percent of the current investigative workload aren’t insurmountable, OPM said, but the risks of the transfer could lead to delays.

“In that three-year plan, they’re dependent on transferring large numbers of people and capabilities from OPM or elsewhere into DoD in order to fulfill the mission,” Chvotkin said. “If OPM doesn’t have enough investigators now, then transferring 75 percent of NBIB’s workforce is a risk. DoD viewing this as a three-year transition effort worries me a lot.”

“If OPM doesn’t have enough investigators now, then transferring 75 percent of NBIB’s workforce is a risk. DoD viewing this as a three-year transition effort worries me a lot.” — Alan Chvotkin, executive vice president, Professional Services Council

With the transition will come separate offices, support services contracts and investigative procedures as DoD stands up an organization to handle 75 percent of the current clearance workload, while NBIB processes the remaining 25 percent.

It’s also a concern that Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.), chairman of the Oversight and Government Reform Government Operations Subcommittee, voiced during a hearing in October.

“I am skeptical that we are going to get all these unbelievable efficiencies just by moving it from one government agency to another,” Meadows said. “[What] we’re going to do is end up with duplicative services, and I’m all about shared services. … But what I’m not about is allowing DoD and OPM to do the same thing when, Mr. Phalen, you said that the basic problem that you have is getting talent to actually do these checks.”

OPM, which is helping agencies prepare for the Trump administration’s efforts to reorganize government and reduce the size of the workforce, also questioned whether DoD’s plan aligns with the reorganization initiative.

“Because of the inevitable duplication of processes, it will create long-term systemic obstacles to reform and disrupt the current security clearance system,” the agency’s acting director, Kathleen McGettigan, wrote in a Sept. 6 letter to Congress, which Federal News Radio obtained. “A blow to the efficiency of that process is a blow to efficiency — and effectiveness — across government.”

Coming full circle

Despite concerns from OPM and DoD, Congress seems to think the Pentagon will be able to manage its own security processes better than NBIB can now.

But just 13 years ago, Congress stripped DoD of its security clearance program for the same reasons NBIB is getting cut out of the picture.

When it still owned the security clearance process, DoD declared its security clearance a “systematic weakness” due to problems with the department’s backlog of clearances and delays in determining eligibility. The Government Accountability Office added DoD’s security clearance program to its High-Risk List in 2005.

In part two of Federal News Radio’s special report, “Is splitting the security clearance process destined for failure?” we will uncover how the security clearance backlog got so high and how DoD mismanagement was a factor.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED