DOJ employees call for governmentwide plan addressing sexual misconduct

The White House tasked agencies with updating their sexual misconduct response policies in 2021. But DOJ GEN says the steps to get there are unclear.

Agencies are expected to address and prevent sexual misconduct and harassment in the workplace, but a group of federal employees is raising concerns about ambiguity in the steps needed to actually meet those expectations.

Without a clearly defined blueprint for responding to instances of sexual harassment, the Department of Justice Gender Equality Network (DOJ GEN) warned that agencies will underestimate the scale and significance of the problem.

But the solution, according to DOJ GEN, involves the Biden administration taking governmentwide action, pushing agencies further and creating a centralized team to address sexual misconduct in the federal workplace. In a letter sent earlier this month to the White House Gender Policy Council and the Office of Personnel Management, the group called for either an executive order or regulations to try to mitigate the issue.

“Many DOJ GEN members can personally attest to the profound harm that sexual misconduct causes individual victims,” DOJ GEN wrote in the Aug. 8 letter, shared with Federal News Network. “We have also seen how it degrades the integrity of federal agencies and undermines their missions.”

In a 2021 report, the Merit Systems Protection Board estimated that 21% of women and 9% of men in the federal workforce had experienced sexual misconduct in the workplace within the last two years. But because sexual misconduct often goes unreported, the available data may not show the full extent of the problem. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission estimates that three out of four individuals who experience sexual harassment in the workplace never tell a supervisor, manager or union representative about the incident.

To try to address the pervasive issue, President Joe Biden’s 2021 executive order on advancing diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility included a measure tasking all agencies with creating a “comprehensive framework to address workplace harassment, including sexual harassment.”

The executive order, however, “did not mandate specific steps that agencies must take to create such a framework, and few if any agencies have made meaningful reforms since then,” DOJ GEN wrote in its letter.

To try to fill in the gaps, DOJ GEN outlined steps agencies should consider in updating how they respond to sexual misconduct and harassment. Each agency’s policy will look different based on factors like workforce composition, geographic location and leadership structure. But generally, the employee group said agencies should conduct climate surveys, collect data, create working groups to make recommendations, and then use those recommendations to implement a new policy.

“We want to see the White House and OPM make sure that every agency ensures that their processes are where they should be — and if they’re not, direct them to fix them,” Stacey Young, president of DOJ GEN, said in an interview with Federal News Network. “We thought that providing the White House and OPM with a blueprint of how this could work might be helpful, and we hope that the administration follows through and does what we think it can.”

The White House and OPM did not respond to Federal News Network’s requests for comment.

Rooting out sexual misconduct at agencies

The push from DOJ GEN comes after multiple instances of pervasive sexual harassment in the federal government. Investigations into the Drug Enforcement Administration, an arm of DOJ, as well as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, have revealed long stretches of workplace misconduct across agencies.

“The list could go on,” DOJ GEN wrote. “But it should not take media exposés, congressional mandates or employee advocacy to instigate agency action.”

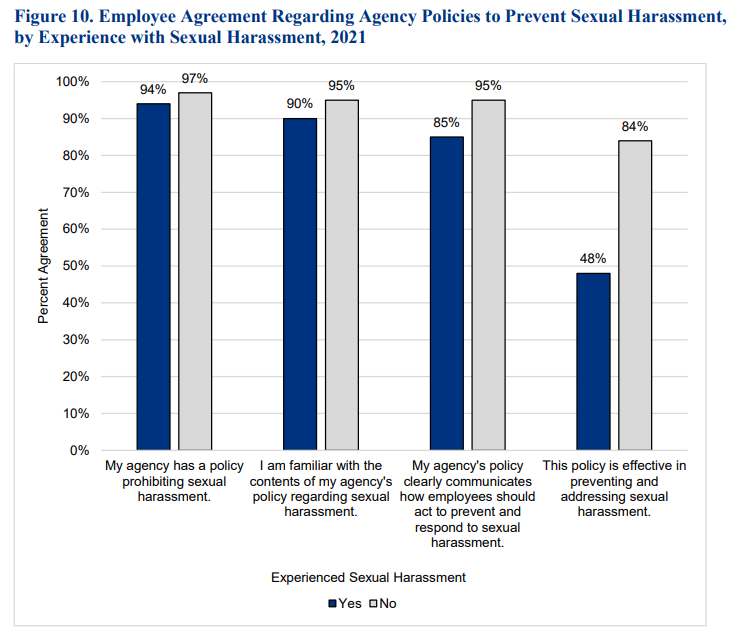

In a 2021 MSPB survey, about 20% of respondents said their agency tolerates comments and actions of a sexual nature that are inappropriate for the workplace. MSPB also found that while up to 97% of respondents said their agencies do have a policy in place, 84% said the policy is effective in preventing and addressing sexual harassment.

Notably, those who have actually experienced sexual harassment in the workplace have more negative views of their agency’s policy — with less than half agreeing the policy was effective.

More recently, a 2024 report from the Government Accountability Office showed that many agencies are struggling to meet criteria of an effective policy to combat sexual harassment and misconduct in the federal workplace.

For instance, while employees can file a complaint with the EEOC, that process is “insufficient” in many cases, DOJ GEN wrote. MSPB’s report showed that 41% of federal employees surveyed did not file an EEO complaint because they did not think the outcome would be worth the effort.

The challenge is also unique for federal employees, since they have a much shorter window of time to file a complaint. Specifically, federal employees have just 45 days after an incident of sexual misconduct occurs to submit an EEO complaint. By comparison, workers in the private sector have 180 days to file a complaint.

“That’s a huge and unjustified discrepancy,” Young said. “We would like to see, ultimately, the EEOC promulgate a regulation allowing employees in the federal sector to have as much time to file a complaint of discrimination as employees in the private sector currently have.”

DOJ’s system for responding to sexual misconduct

The letter also pointed to DOJ, as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), USAID and the Peace Corps as examples where sexual misconduct response systems have been working well.

In its letter, DOJ GEN recommended that other agencies follow those leading examples to update their own policies addressing sexual misconduct. The employee group described DOJ’s sexual harassment response system, which it first developed and implemented in 2021, as “groundbreaking.”

The changes at the department came after many years of employees experiencing sexual harassment and misconduct on the job, Young said. As a result, DOJ launched a steering committee to examine how the department was handling instances of misconduct.

The committee eventually released a set of recommendations on how to implement policies that would support workplace safety, update employee training and better address complaints of sexual misconduct. And following the committee’s recommendation report, obtained by Federal News Network, DOJ created a centralized unit to manage the various components of the issue, called the “sexual misconduct response unit.”

“We know that every agency could go through the same process that DOJ did,” Young said. “We think that what DOJ did could serve as a model for other agencies, and we hope that the administration will require all agencies to go through a similar process.”

NOAA’s policy is location-specific, risk-specific

A handful of other agencies have similarly revamped their programs for responding to sexual harassment. NOAA, for one, began developing a new sexual misconduct response policy following requirements from the fiscal 2017 National Defense Authorization Act. And in 2018, NOAA recruited a director of workplace violence prevention and response, Kelley Bonner, to spearhead the design and implementation of the new program.

When she first stepped into the agency role, Bonner said there was a near-immediate shift from agency employees who had experienced sexual harassment. The creation of the new program at NOAA quickly led to an influx of reports from employees.

“Once people knew someone was there to help, people started calling,” Bonner, who currently works as a strategic risk management advisor, said in an interview with Federal News Network. “People started calling, saying, ‘This happened to me. Can I talk to you?’”

To create the program at NOAA, Bonner focused on both accountability and victim advocacy. In other words, the work centered on improving enforcement mechanisms for those who engage in sexual misconduct, as well as offering support for victims of harassment. NOAA also focused on training employees to help them understand the basic definitions of sexual misconduct and harassment, and where actions crossed the line.

But beyond that, creating a location-specific, risk-specific approach to handling sexual misconduct was also key, Bonner said. For example, NOAA employees stationed in remote areas like Alaska and Antarctica are at a higher risk for experiencing sexual misconduct, since the workers are generally more isolated.

“Those folks need a specific type of education and prevention rooted in ‘strategic resistance,’” Bonner said. “That’s all about how to get to safety when you have no one coming to help you, and you might be by yourself.”

By comparison, NOAA employees at agency headquarters or in an office setting required a different approach to address sexual misconduct and harassment, Bonner said, including scenario-based training and education on bystander intervention.

“Sexual misconduct exists on a continuum, so you want to put a lot of energy and effort into tackling the root causes of it — like toxic workplaces — and through that lens, providing a really robust response,” Bonner said. “We need to be more transparent to have people understand who’s impacted what we’re doing about it. [We need to understand] that people who have marginalized identities are more likely to be victimized. And last but not least, [we need to] educate leaders on the risks of sexual misconduct to the mission itself.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED