Employment attorneys see more proposed firings, fewer settlements under VA Accountability Act

The Veterans Affairs Department recently clarified its disciplinary data, which the department posts publicly on its website every two weeks.

The Veterans Affairs Department under the first full year of the Trump administration fired 2,537 people — about 500 more federal employees than the agency let go in 2016.

VA recently clarified its disciplinary data, which the department posts publicly on its website every two weeks. The latest statistics now include the number of employees who have been removed during their one-year probationary periods.

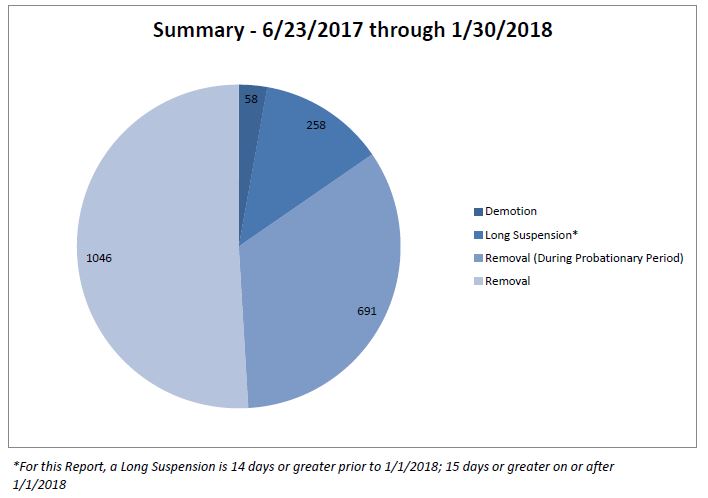

Since President Donald Trump signed the VA Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act into law at the end of last June, the department has fired 1,737 people, including 1,046 removals and another 691 employees who didn’t make the cut during their one-year probationary period, VA spokesman Curt Cashour said in an email last week.

It fired 2,001 people in 2016, which included 983 removals and another 1,018 probationary removals, Cashour said.

The president touted the success of the VA Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act in his State of the Union address last week and called on Congress to extend the law’s authorities to every cabinet secretary.

During calendar year 2017, VA fired 1,443 people and removed 1,094 probationary employees, Cashour said.

Among the department’s removals for calendar year 2017 are:

- 177 housekeeping aides, leads or supervisors,

- 84 food service workers,

- 40 physicians,

- 116 nurses,

- 28 veterans service representatives,

- 9 contract specialists,

- 9 human resource specialists and assistants,

- 8 senior leaders, and

- 12 supervisors.

Housekeeping aides, custodians and cafeteria workers still made up the bulk of the department’s removals in 2017, but federal employment lawyers say they’re seeing more GS-11s and 12s, or others with the means to hire an attorney, request their services in recent months.

“There’s definitely been a shift. I see it every day,” said Debra D’Agostino, a federal employment attorney with the Federal Practice Group. “We have gotten bombarded with VA removal cases, and I don’t think we’re alone. I’ve heard from some of my opposing counsels who work at the VA that they’re completely swamped with these cases. It does seem like there’s been a big uptick and at higher levels where people are filing appeals and hiring lawyers to challenge the removals.”

Michael Macomber, a partner with Tully Rinckey, said his law firm has also seen more matters from VA employees since the accountability act became law but acknowledged he’d started to see a growing number of VA cases before then as well.

But VA Secretary David Shulkin’s decision to require senior level approval for employee settlements of $5,000 and above has perhaps sparked the most noticeable difference.

“Settlements have completely [ground] to a halt, which means more cases are being litigated at the taxpayer’s expense,” D’Agostino said.

Macomber agreed, adding that the decision has put a “kibosh on settlement discussions” at the department.

“It’s posed some unique problems on cases that really should come to some sort of resolution but can’t,” he said. “I have a fee petition out there right now, which for all purposes, the agency’s dead to rights on, but I can’t get any discussions on it. We had to file a whole fee petition [and] everything else, costing more and more money, which the agency’s going to be responsible for on the back end because we couldn’t resolve it, and we tried.”

Federal employee groups blasted the president’s call to expand the firing authorities to all cabinet secretaries.

“Current law and regulations that govern the federal workforce allow for ample options to reward good performers and discipline or remove employees for poor performance and misconduct,” Randy Erwin, president of the National Federation of Federal Employees, said in a statement. “On average, several thousand employees are removed from service every year and tens of thousands are disciplined for performance or misconduct. The law itself is not the problem, and this is proven each year through thousands of successful adverse personnel actions by managers who are properly trained.”

Rather than expand the VA Accountability Act or create a new law, Congress should help agency leaders better understand the authorities they already have to fire and discipline poor performers, said Bill Valdez, president of the Senior Executives Association.

“Every cabinet agency head has ample authority on the books to ensure accountability, but they are not fully utilized for a variety of reasons, including culture and political climate,” he said in an email. “Managers don’t feel supported by their senior management when taking actions against poor performers or those who exhibit misconduct. Employees have too many avenues for appeal and ways to throw sand in the gears of the accountability system.”

A Merit Systems Protection Board 2016 survey of agency supervisors suggested a similar sentiment. According to MSPB’s survey, half of agency supervisors and managers said they were confident they could fire an employee for misconduct.

About 80 percent of supervisors said their agency’s culture on removing employees for misconduct posed the biggest challenge in firing “bad actors.”

Roughly 60 percent acknowledged one barrier to the disciplinary process was their understanding of that process itself. MSPB, however, argued more supervisors may not understand the removal process or the law behind it. According to statute, agencies must find that a “preponderance of evidence” supports their decisions to fire an employee.

“When we surveyed proposing and deciding officials for removal actions that occurred, 90 percent of proposing officials and 84 percent of deciding officials reported that the standard they used was ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ — the level of proof our legal system requires in order to send a person to prison or even give them the death penalty,” MSPB wrote.

Under the VA Accountability Act, the department must show “substantial evidence” that an employee or senior executive committed misconduct or performed poorly — a lower standard than the current “preponderance of evidence” that most other agencies must demonstrate when faced with a similar disciplinary case.

Macomber noted that VA human resources specialists and managers still seem to be confused by the evidentiary burden.

“For the most part, it is a lower evidentiary burden,” he said. “The agencies are equally confused by that at times. When this first came out, I don’t think they knew how this was going to shake out. I still think there’s a fair level of uncertainty to it, as there’s very little case law to support that — what process is due, what does the agency need to consider, do they still need to consider mitigating evidence or not even if it is at the administrative level? There’s a lot of uncertainty even through the local HR offices and things of that nature.”

Earning their managers’ support to remove employees, as well as the services they received from their agency’s human resources office, were among the other challenges supervisors mentioned in MSPB’s survey.

“The perceptions reported by supervisors indicate that there is not just one barrier that poses a challenge to removing employees, but it also shows that many of the strongest barriers that potential and proposing and deciding officials face come from within their own agencies,” MSPB wrote. “The good news for agencies is that if agencies are the source of the problem, then they can be the source of the solution.”

Better training could help career leaders better understand the authorities they already have to hold their employees accountable, but improved education could also help political appointees understand why career executives struggle to fully use those authorities, Valdez said.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED