DoD spending doesn’t align with push for innovation and near-peer competition, analysts say

The Defense Department is talking the talk, but there is no walk in the spending numbers.

It’s been four years since the Defense Department announced its intention to focus more on innovation to outmaneuver potential adversaries and keep its technological edge through the “third offset” strategy.

The push — reinforced in Defense Secretary James Mattis’ national defense strategy — has been publicized as an effort to increase the Pentagon’s outreach to companies that don’t traditionally work with the agency in order to harness technologies like man-machine learning, artificial intelligence and big data analytics.

However, a new study of recent DoD contract trends by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) showed that while the Pentagon is spending more money, it’s still going to the same firms: Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Raytheon, Boeing and Northrop Grumman.

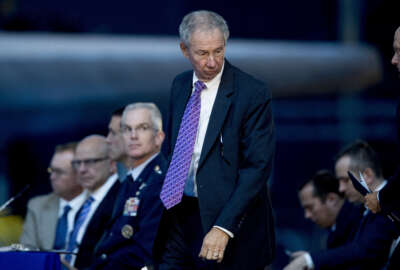

This spending is “not consistent with the idea that we have embarked on a vast strategic undertaking to focus on peer competition and that’s why we are spending more money on contract obligations,” Andrew Hunter, the report’s lead author told reporters Nov. 27.

Hunter said it seems that DoD is investing in places where it can reliably spend money, like existing production lines, instead of directing funds toward new companies and next-generation technologies like the current National Defense Strategy and the Third Offset Strategy direct.

According to the CSIS data, DoD contract obligations increased by 13 percent from fiscal 2015 to 2017. The lion’s share of the growth went toward spending on products, which increased by 22 percent. Services contracting grew by 5 percent, and research and development grew by 6 percent.

“The big bounce back has really been led by spending on ‘stuff,’” Hunter said. “I think that makes sense if you look at how the new money came about. The impetus was really coming from Congress. Congress likes to add money to existing production lines, F-22s, F-35s, B-21s, KC-46s, C-130Js, all the things that Congress likes to add because it’s very concrete and members can get their mind around it.”

Hunter added it’s not all Congress’ fault, though. He said in his talks with the Army, the service put extra money in things like Black Hawk helicopters instead of in next-generation research.

“When the National Defense Strategy says what we need to invest in is artificial intelligence and human-machine teaming, then why is all the new money going into aircraft?” Hunter said. “I don’t look at this and see how the defense strategy has clearly shaped this spending.

He said when the military got a $15 billion supplemental boost in funding in 2017, the Army knew it needed to invest in modernization. But the reasoned that it it would be unwise to ask appropriators to spend a “wedge” of those funds on next-generation technologies, because Congress would simply redirect them elsewhere.

“We are going to put it in helicopter programs where there is production in well-known congressional districts with people who serve on committees for an F-35, so that money is going to be approved and we can execute it.” Hunter said. “That way it’s not going to sit there as unspent money that goes away at the end of the year. There’s powerful incentives on both sides.”

Research and development funding stayed relatively stagnant for the past 20 years. However, many of the small and innovative businesses DoD wants to court can make their name in the R&D area.

While DoD and the services screaming for the attention of these companies through initiatives like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), the Strategic Capabilities Office, rapid capabilities offices and initiatives aimed at startups, the number of new entrants to the defense industry marketplace has been declining since 2005. About 5,700 new companies worked with DoD in 2016, about 4,200 were small businesses. That’s compared to more than 22,000 in 2005.

The companies don’t stick around for long either.

“The survival rates show around 40 percent of new entrants exit the market for federal contracts after three years, around 60 percent after five and only about one-fifth of entrants remain in the federal contracting arena after 10 years,” the study stated.

Hunter said the work programs like DIU and others are doing is important, considering how defense corporations continue to consolidate into larger conglomerates, for example, Lockheed Martin buying Sikorsky and L3 and Harris Corporation merging last month.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED

Related Stories