The agency for much of this year has balanced conducting an extended tax filing season with sending more than 160 million payments worth $270 billion in pandemic...

The IRS, over a decade of budget cuts, has become accustomed to doing more with less. But the unprecedented workload put on the agency during the COVID-19 pandemic has shined a spotlight on an agency stretched beyond its limits.

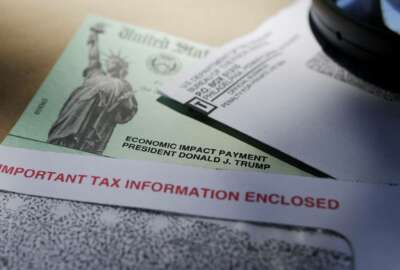

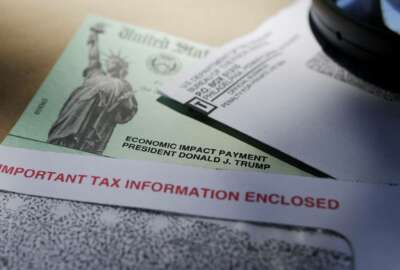

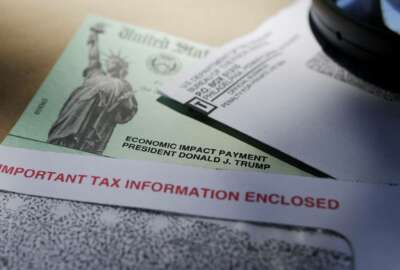

The agency for much of this year has balanced conducting an extended tax filing season with sending more than 160 million payments worth $270 billion in pandemic stimulus funding across the country.

The IRS issued about half of its Economic Impact Payments within the first two weeks of Congress passing the CARES Act, with little guidance from lawmakers or an agency playbook to carry out its obligations.

To pull this off, IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig said much of the agency’s IT staff worked 15-17 hours days, seven days a week between March and July. The same IT workforce that handled the tax-filing season was also responsible for implementing the Economic Impact Payments.

The agency also broke its own record for timely processing of tax returns, processing more than 2 million returns per hour, or more than 600 returns per second without any technological errors.

The earliest waves of pandemic stimulus payments went to households that filed 2018 or 2019 tax returns, but to reach many of the individuals in most need of an emergency check from the federal government, the IRS had to stand up an online portal for households that don’t ordinarily file federal tax returns.

Rettig said more than 14 million people so have signed up for stimulus payments through that portal.

“Our same IT folks took care of all of that. At the same time, we did not have the luxury of onboarding hundreds or thousands of folks to help us in that situation. We had people who had to multitask,” Rettig told members of the House Oversight and Reform Committee’s subcommittee on government operations on Wednesday.

For context, the IRS has done all of this with a budget that, according to the Congressional Budget Office, is about 20% less than what it had in 2010, and has lost about 20% of its workforce to attrition. Nearly a third of that staffing loss has come from the agency’s enforcement branch.

The agency’s diminished resources have been a point of contention for years, but citing lavish conference spending and the agency’s review process for tax-exempt groups under the Obama administration, Republicans in Congress remain skeptical of restoring the billions of dollars that the IRS has lost throughout the years.

While those pleas for additional funding went unheeded by the previous IRS Commissioner John Koskinen, Rettig, President Donald Trump’s pick to lead the agency, has also faced an uphill battle convincing lawmakers to restore the agency’s budget levels seen a decade ago.

The agency’s response to the pandemic, Rettig told lawmakers, “serves to illustrate how critical it is for the agency to receive consistent, timely, and adequate multi-year funding such that we can succeed in providing the services that our country so rightly deserves.”

Subcommittee Chairman Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) agreed with that assessment and warned that the IRS’s capacity to meet its mission has been undercut for years because of its gutted budget.

“Today, when the American people are relying on the IRS the most, the agency is gasping for air,” Connolly said.

Beyond cuts to its enforcement operations, the IRS has deferred updating and replacing its legacy IT systems, and continues to operate on legacy programming languages like COBOL that are unfamiliar to incoming hires. The agency’s IT budget has been flat for about 10 years.

“It’s hard to find staff that know these skills,” said Vijay D’Souza, the Government Accountability Office’s director of IT and Cybersecurity. “Programmers today aren’t coming out of school learning how to do programming languages that are 50 years old.”

Those deferred IT investments have led to years of the IRS getting low marks from the National Taxpayer Advocate for things such as poor levels of service on tax-help hotlines or the agency’s fragmented view of a taxpayer’s history of asking for assistance.

“The IRS desperately needs more resources to do its job of helping taxpayers and collecting revenue,” National Taxpayer Advocate Erin Collins said. “If the IRS continues to be starved its resources, it will continue to struggle.”

While the IRS struggles with its correspondence during a normal filing season, this year it also had to juggle messaging with Capitol Hill about its rollout of the CARES Act.

To facilitate this commination, the IRS this spring stood up a phone line for Congress that quickly became overrun with calls from House and Senate staffers.

That prompted Rettig to suggest standing up a dedicated email inbox for congressional inquires that that agency would check around-the-clock, but soon that also became untenable, with more than 100,000 incoming inquiries.

“My bright idea really overran us as well,” Rettig told the subcommittee about his email inbox plan.

As of the end of September, the IRS has received nearly 13 million paper tax returns, but has an overall mail backlog of more than 5 million pieces.

The agency estimates that about half of that mail is tax returns. At the peak of its backlog between March and April, Rettig said the agency had about 23 million pieces of unopened mail, but the agency is running two shifts a day and has offered overtime to process about 1.3 million pieces of mail a week.

The IRS and Treasury Department made speed a top priority for pandemic payments in the weeks after Congress passed the CARES Act, and in doing so sent more than a million payments to the deceased.

While the IRS garnered plenty of notoriety for a GAO report that found more than $1 billion in pandemic stimulus payments went to deceased or incarcerated recipients, the agency and its partners have gone to great lengths to claw back those funds. Rettig said the agency has seen a net total of $300 million in improper payments from the EIP program.

While the president has put a hold on his administration negotiating new rounds of pandemic spending before Election Day, Rettig said the IRS, having gone through “substantial programming” for the last round of getting payments out the door, would be in a much better place to disburse another round of funds to the public.

“We’re as prepared as we could be, but we are better prepared than we were the last time, and I think we did admirably the last time,” he said.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jory Heckman is a reporter at Federal News Network covering U.S. Postal Service, IRS, big data and technology issues.

Follow @jheckmanWFED