Biden’s nominees requiring Senate confirmation take 127 days, on average, to get through the process, the Partnership for Public Service said.

President Joe Biden has yet to name nominees for the Social Security Administration’s top two leadership positions. The Office of Personnel Management hasn’t had a deputy director in nearly two years. And Biden just withdrew his nominee for controller at the Office of Management and Budget.

This handful of vacancies points to a much larger problem: the White House is struggling to nominate and get federal leaders confirmed by the Senate. It’s an issue that’s existed for at least the past few administrations, and it’s getting worse.

So far under Biden, it has taken nominees 127 days on average to reach Senate confirmation, according to the Partnership for Public Service. That’s including all full-time positions, except for judges, U.S. marshals and attorneys. In comparison, the average length of the Senate confirmation process was 115 days during the Trump administration and 112 days during the Obama administration.

Beyond the actual length of the process, there are also proportionally fewer confirmations for this administration. In Biden’s first year in office, the Senate confirmed 55% of his nominations. That’s compared with 75% for George W. Bush, 69% for Barack Obama and 57% for Donald Trump in their first years on the job.

It’s not just the lengthening Senate process that’s leading to fewer confirmations, but rather a perfect storm of three separate components — the administration, the Senate and the nominees themselves.

“The White House is oftentimes slow in submitting nominations to the Senate and the paperwork submitted on behalf of the nominee has been incomplete. Even when the nominee’s submission is fully complete, he or she often faces a Senate process whose pace at moving nominations has been described as ‘glacial,’” former OPM Deputy Director Dan Blair said in an interview.

Approximately 4,000 federal positions require a presidential appointee or nominee, and roughly 1,200 of those civilian positions need Senate confirmation. Of the some 800 full-time positions that the Partnership for Public Service and The Washington Post track, Biden has so far nominated 593 candidates, and the Senate has confirmed 465 of those. The Senate is still considering another 125 of Biden’s nominees, while 77 positions don’t have nominees at all.

The number of positions requiring a presidential appointment is also increasing. Between 1960 and 2016, the number of positions needing Senate confirmation increased from 779 to 1,237 — a growth of nearly 60%. In the last 11 years alone, there were another 60 Senate-confirmed positions added to the list, said the Partnership’s Vice President of Government Affairs Kristine Simmons.

“The Senate confirmation process has become longer and resulted in a lower confirmation rate of first-year nominations for each successive administration since President George W. Bush,” Simmons wrote in testimony from March. “The average time to confirm a nominee has nearly tripled since the Reagan administration.”

The departments of Defense and Justice, as well as the Executive Office of the President, which houses OMB, all have relatively high numbers of vacancies compared with other agencies. Notably, the State Department currently has 46 vacancies — the most of any executive branch agency. The Biden administration, though, has picked nominees for many of the currently unfilled positions.

A vacancy doesn’t always mean that no one is working in the position. In most cases, an acting official will work in a vacant position until the Senate confirmation process is complete. Acting position-holders are a temporary solution to the worsening vacancy challenge, but that approach has its own host of problems.

“Temporary acting officials – as talented as they may be – often are reluctant to make long-term decisions that will bind their successors, thus kicking important policy, strategy or operational decisions down the road,” the Partnership’s Director of Policy Troy Cribb wrote in an email to Federal News Network.

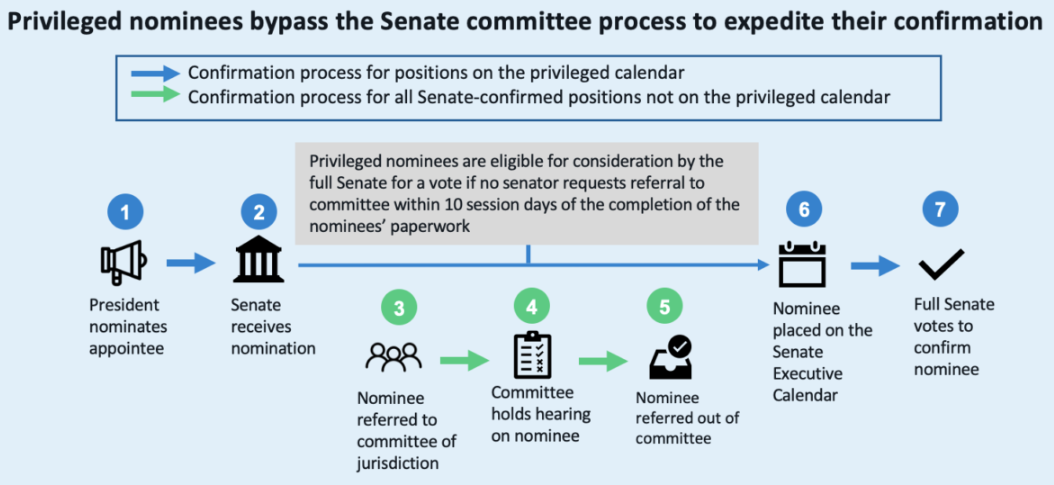

Another workaround aiming to partially expedite the confirmation process is the “privileged calendar,” which in theory speeds up the process for about 280 typically non-controversial, presidentially appointed positions. The privileged calendar, which the Senate created about 10 years ago, lets candidates bypass the typical committee hearing process and move straight to a floor vote for full Senate approval.

Although it has good intentions, that process can often hit a snag, said Carter Hirschhorn, an associate manager at the Partnership for Public Service.

“While the process allows nominees to bypass committee review, it does not provide for an expedited procedure once it reaches the full Senate. As a result, once privileged nominees are placed on the executive calendar, they wait alongside all other nominees for the final step of the process – a vote by the Senate. The data shows that positions on the privileged calendar are taking longer to confirm now than before its creation,” Hirschhorn wrote in an Aug. 1 report.

The exact time it takes to complete the Senate confirmation process also depends on the type of position. Inspector general roles, for example, are notoriously difficult to fill — in part because there is no set length of time for the appointments. The IG position has one of the longest wait times between nomination and confirmation, Simmons from the Partnership said. Between 1990 and 2020, it has taken 121 days on average for the Senate to confirm IGs. That creates some lasting consequences. OPM, for example, just got its first permanent IG in six years in April.

And the road to confirmation isn’t easy, either — the challenges pile up even before the nomination takes place. Most presidential nominees have to fill out piles of paperwork — forms for financial and ethics screenings, a questionnaire on either national security or public trust, a public financial disclosure report, and an FBI background check, to name a few. Nominees for Senate-confirmed positions are also required to fill out separate committee questionnaires, according to the Partnership’s Center for Presidential Transition. Then, nominees field questions from the Senate, another not-so-easy process.

“Putting yourself out there for a presidential nomination requires someone who has stamina and who isn’t shy about handling criticism,” Blair said.

Leadership vacancies can negatively affect not only agencies’ day-to-day operations, but also federal employees’ morale. Without senior leaders in place to carry out an administration’s policies, the lack of permanent position-holders may make employees feel uncertain about the future direction of their agency, Cribb said.

“Long-term vacancies in top leadership positions in the federal government create numerous pain points that erode organizational health,” Cribb said. “Vacancies create ripple effects of stress, with other senior officials becoming dual-hatted or triple-hatted as they perform their own jobs while also stepping in to perform duties of vacant positions.”

The effect on the federal workforce especially comes down to operations at OPM. That agency has its own internal challenges, too, including a deputy director seat that’s been empty now for nearly two years.

The tasks of the OPM deputy director fall largely to the director’s discretion — which projects to focus on, and what the biggest priorities are. The deputy can also stand in for the director to support initiatives the director considers most important. Biden nominated Rob Shriver for the position, but the Senate has so far not confirmed him.

“When you have that vacancy, you don’t have an individual to fall back on and rely upon that would have the title and the gravitas to stand in for the director,” Blair said.

Regardless of the actual policy agenda, having both a director and deputy director in place will significantly improve day-to-day work and an agency’s ability to move an administration’s agenda forward, Blair added.

“People may disagree with that agenda, but at least you have a good team in place that opponents, proponents and stakeholders can talk to, listen to and have access to, in order to address these really important issues that are coming up on the federal workforce,” he said.

OPM Director Kiran Ahuja has lauded Shriver’s work as well.

“He has been a key strategic advisor to me during my tenure as director and a leader at this agency since day one of this administration,” Ahuja said in a statement.

The White House is also feeling the pressure building from Congress to nominate position holders specifically for the Social Security Administration. SSA has yet to get its picks from Biden for commissioner and deputy commissioner, the agency’s top two positions. Acting Commissioner Kilolo Kijakazi is SSA’s stand-in for the time being, but Senate lawmakers said that’s far from a long-lasting solution.

“Nominating and confirming a permanent commissioner and deputy commissioner would provide accountable leadership to the agency and reassure the public of SSA’s commitment to supporting the vulnerable populations that rely on its programs,” a group of Senate Democrats wrote in a Sept. 27 letter to the White House, urging Biden to make the nominations.

SSA’s lack of permanent leadership dovetails with ongoing agency workforce challenges. The agency’s employees have some of the lowest scores across government for employee engagement and satisfaction. Pulse survey respondents at SSA reported poor work-life balance and high exhaustion.

“Permanent, Senate-confirmed leadership at the agency will help improve this longstanding challenge for the agency and its employees,” the lawmakers wrote.

SSA has also been working to rebuild its relationship with its union, the American Federation of Government Employees. The two parties have been renegotiating their national contract, most recently restoring previous levels of official time for employees.

Beyond Biden withdrawing his nominee for controller — a role that hasn’t had a permanent position-holder since 2017 — OMB has several other politically appointed positions that remain unfilled.

There are vacancies for the leadership roles at both OMB’s Office of Federal Procurement Policy and Office of Federal Financial Management. The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs has a nominee, but the Senate has yet to confirm him. Though not a position requiring Senate confirmation, OMB also lost one of its top federal workforce leaders, Pam Coleman, after she stepped down in August from her position as associate director of performance and personnel management.

Dave Mader, former OMB controller from the Obama administration, said it’s been a significant challenge getting nominations through the Senate confirmation process. It’s compounded by other legislative priorities, too, like working to pass the budget, and focusing on COVID-19 and infrastructure spending legislation.

“I think that’s a good conversation to have, because it’s important for any administration to be able to quickly fill critical positions,” Mader said in an interview. “I think it’s something that should be examined more thoroughly.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED