Salary Council members make official case for comprehensive federal pay changes

Three members of the Federal Salary Council have made their official recommendations to the President's pay agent suggesting how to improve the way government...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Three members of an advisory council appointed by President Donald Trump have quietly proposed a series of comprehensive recommendations that could change the way government evaluates and then compensates federal employees.

The Federal Salary Council first unveiled five recommendations at a public meeting back in November. But in its latest report, dated May 2, the council provides more detail on these five suggestions.

The recommendations are meant to serve as a series of official recommendations to the President’s pay agent, a body comprised of the directors of the Office of Personnel Management and Office of Management and Budget and the Labor secretary.

It’s perhaps one of the first times the Federal Salary Council — a relatively unknown governmental body meant to help the President ultimately make decisions about employees’ annual locality pay adjustments — has suggested such comprehensive changes to the way the federal workforce is compensated.

The report also shows just how polarizing the issue of federal employee compensation has become.

To be clear, the members’ eight-page argument represents a minority of the opinions of the council. Five of the salary council’s members, which include individuals representing the American Federation of Government Employees, National Treasury Employees Union and National Federation of Federal Employees, strongly disagree with the pay methodology recommendations.

They describe them as a “clear attempt to politicize” what has traditionally been a highly technical and complex process by the council, OPM and Bureau of Labor Statistics to set locality pay rates. The unions’ views are also included in the salary council’s report.

But three of the council’s members, including Chairman Ron Sanders and members Jill Nelson and Katja Bullock, made a detailed argument for change.

“We are advocating changes, looking first within the law, and then to changes in the law itself. Working within the law, that is [the Federal Employees Pay Comparability Act], we believe that there is an opportunity to revise and/or augment the current methodology to improve its accuracy and credibility,” the members wrote.

Current methodology diluted by budget constraints

The methodology the council currently uses, members said, doesn’t paint a complete picture of what it’s supposed to demonstrate — the gap between federal employee salaries and their counterparts in state and local government and the private sector.

That gap, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics has said sits at about 31%, ultimately informs pay raises in the form of locality adjustments for federal employees during most years.

Related Stories

Gov’t spends 17 percent more on feds’ compensation than private sector, CBO says

“Over the years, that methodology has been diluted because of budget cuts,” he said in an interview. “As we say… BLS and OPM have the best methodology that their budgets can buy. But I don’t think anyone is going to argue that the methodology that they currently employ, because of budget constraints, is ideal to determine pay comparability.”

Council members argued that a single number is too simplistic, a “mathematically derived average of averages” that doesn’t tell the complete story.

Specifically, the current methodology isn’t sensitive to certain occupations that are unique to the federal government or the complexities of the 70-year-old General Schedule, council members said.

They reference their interactions with federal employees, managers, unions and the local Chamber of Commerce in Charleston, South Carolina, who have described agencies’ challenges to recruit, retain and talent in the area.

Despite these anecdotal challenges, Charleston has, year after year, failed to meet the statistical requirements needed to secure its own locality pay.

“We find that some occupations (especially those requiring STEM or medical/healthcare skills) are likely substantially underpaid, particularly at entry-level and upper grade levels, and would warrant some sort of pay differential, while other occupations are just the opposite,” the three members wrote. “But the single-number ‘pay gap’ for Charleston is supposed to indicate that all is well, when those who have to live with that number tell us otherwise.”

Instead, the three council members said, highly skilled but underpaid federal employees leave government, while overpaid workers stay.

The council members, however, tread carefully around the unions’ views and actively disputed them.

“While some may suggest otherwise, this is not about reducing the pay and/or benefits of federal employees,” they wrote. “Indeed, the work they do is to be honored and valued, and they should be compensated accordingly — no more but no less. We may disagree with our colleagues over how to best achieve that goal, but it is one we share with our colleagues.

It’s now up to the pay agent to accept and move forward with any or some the recommendations.

Pay methodology recommendations

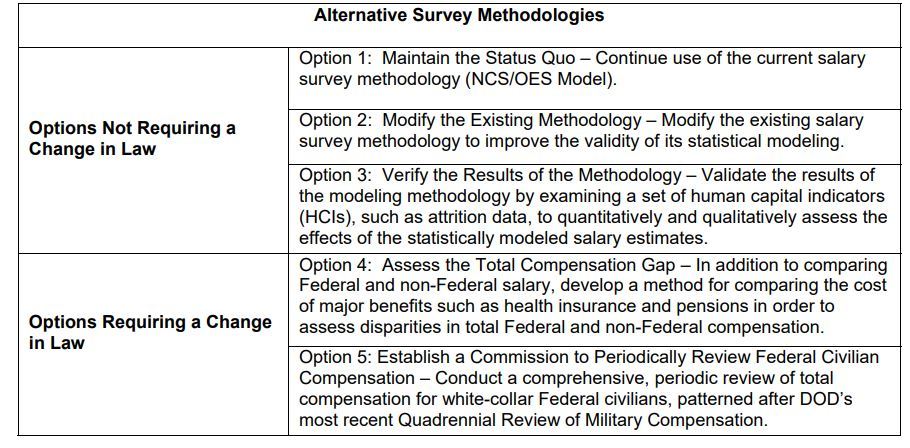

The three members’ recommendations range in scope and ambition.

Three recommendations are ones the President’s pay agent could implement administratively.

The council, for example, urged the President’s pay agent to approve and fund changes to the existing pay methodology to allow OPM and BLS to revert back to “previous and proven and more accurate approaches to salary surveys.”

They suggest enhancing the current statistical formula to benchmark more specific federal jobs against others, a method that the council said BLS initially used back in 1996.

“The costs of studying those methodologies in more detail and then the cost of implementing one or more of those alternatives, frankly, pale in comparison to the size of the federal payroll,” Sanders said. “This is not, I repeat not, a criticism of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or OPM. They’re doing the very best they can with what they have. But we know they can do better, because they did. When they had more resources, they were able to employ a much more robust methodology that, in my view, brought with it a much better credibility when it came to either locality pay adjustments or an overall schedule adjustment.”

The council could also use a methodology and a series of other data, including agency attrition rates, employee engagement scores, job acceptance rates and other statistics, to inform their decisions about which areas are eligible to secure their own locality pay designations.

Members said whether agencies have — in certain locations — used pay flexibilities to combat recruitment, retention and attrition challenges, should also be another consideration.

“Organizations and areas seeking locality pay often come to the council as a first resort, rather than as a last one, in many cases because their parent agency has refused to approve the use of more targeted pay flexibilities that could very well solve their problem,” members said. “Note that there is no requirement to try those flexibilities first, nor is there even a requirement that organizations in a particular area even tell us one way or another. We think there should be.”

In addition, the three council members made two recommendations that would require help from Congress.

One option suggests the government compare federal employee pay, along with pensions, health and life insurance, to those benefits in the private sector. This recommendation represents a “total compensation” approach.

“If comparability is all about competing in the labor market, and the federal government’s benefit package is one of the things that make it most competitive, how can we ignore it?” the three members wrote. “Indeed, the public and private sector employers we talk to are aghast that we do.”

The final option recommends the commissioning of an official review of the federal compensation system. The three members reference the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission as a potential model.

The council members reference potential costs of these studying and then implementing any one of these five recommendations but argued the expenses would be worth it given the size and importance of the federal civil service.

Council recommends another new locality pay area

The salary council, according to the most recent report, has in fact recommended a new locality pay area for 2020. It suggested the pay agent establish Des Moines, Iowa, as a new locality pay area.

The pay agent must first approve the addition of a new locality pay before the President finalizes the move. In the past the establishment of a new locality pay area, at least in recent memory, has taken years for employees in some locations.

The President most recently approved the creation of six new locality pay areas, bringing the total number of distinct areas to 53. This total includes the “rest of U.S.,” a term used to describe the federal employees who don’t work within the 52 separate areas.

Employees in these six new areas saw relatively small locality pay bumps in 2019 compared to the adjustments they previously received under “rest of U.S.,” a phenomenon that could occur more often as OPM and the President add more and more distinct areas.

“The ‘rest of U.S.’ is becoming smaller and smaller and smaller, and when you have a limited amount of dollars to go around — particularly in dividing up the dollars against an across-the-board pay increase versus locality increases — eventually you’re spreading that peanut butter very, very thin,” Sanders said.

The May report from Sanders and the rest of the council was delayed, in part, due to the 35-day government shutdown that furloughed OPM employees who provide technical and administrative support to the council.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED