Correa on innovation: ‘You support it, you nurture it, you invite it, but you don’t force it’

Soraya Correa, the former chief procurement officer at the Homeland Security Department, sought to nurture and promote innovation throughout her career.

The Procurement Innovation Lab (PIL) at the Department of Homeland Security saw the number of projects they worked on last year increase by 117%.

These 37 projects, which were worth a total of almost $3 billion, included everything from a deployment tracking system for FEMA to external parking garage services for the Secret Service.

Soraya Correa, who recently retired after 40 years in government, including the last six as Homeland Security’s chief procurement officer, said six years into the PIL’s existence, the benefits to her former agency’s acquisition process is clear.

“What the PIL has done really well is the whole testing and sharing framework. We invite the procurement teams in to tell us what they want to try or how they want to try something. Sometimes we guide them, and we say to them, ‘Hey, what you think about this? Would you like to try that?’ Then we spend our time following up with them, checking in with them to make sure that they’re going down the right path, answering any questions that they might have. Once they try the technique, whatever that technique may be or new approach, what we do is we invite them, especially if they were successful, but even if they weren’t successful, to host the PIL webinar and tell us about their experience,” Correa said on Ask the CIO before she retired on July 31. “When I say tell us, tell the acquisition community of the Department of Homeland Security so others hear what you tried. I believe that when people hear about the experience, about how it went and what they did, and what they learned, it starts to make people feel a little bit more comfortable that we can take some of these risks, and we can try that.”

That culture of trying something, even if it doesn’t succeed — or as Correa likes to say, failure shouldn’t be a dirty word in government — is the basis of the PIL’s education and sharing of best practices.

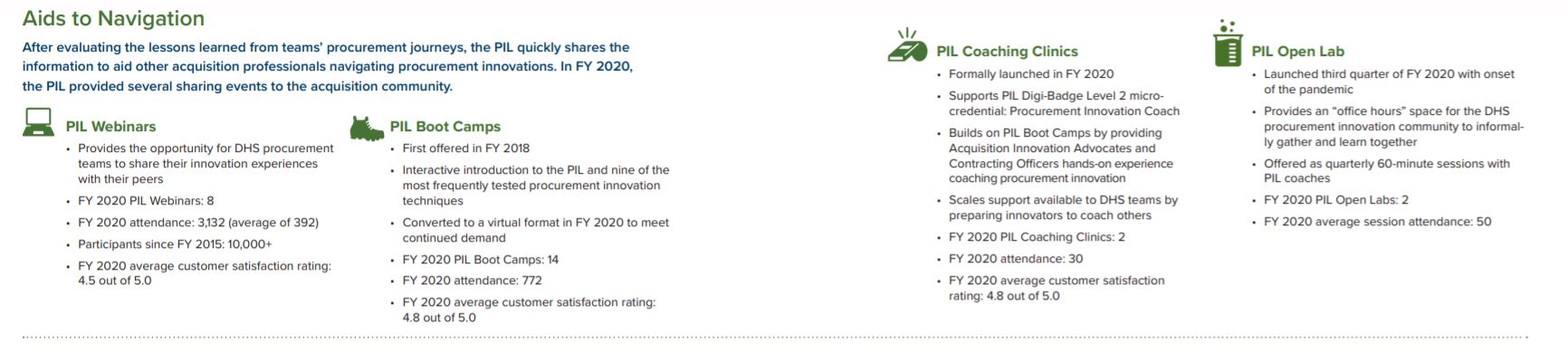

In 2020, the lab said in its annual report that it held 13 boot camps to train acquisition professionals and conducted its 49th webinar in the last five years, attracting, on average, more than 300 people per webinar in 2020.

Correa said the boot camps grew out of requests from other agency acquisition personnel to learn more about how to innovate.

The one-day sessions are part coaching and part educational.

“When I stood up the PIL, I said to the team, and they take this to heart, the best thing you can do is work your way out of job. We’ve got everybody out here innovating, they’re not going to need our Procurement Innovation Lab. My goal is to see procurement innovation labs across. I don’t care if you call them PILs or not. I just want innovative people trying new things, taking risks because here’s the deal, the missions that we serve deserve us trying to do things better, more efficiently and more effectively,” she said. “Today, I have about eight people in the PIL, and then I have pool coaches across our heads of contracting because we’re trying to push this out to everybody. We want them to be the innovators.”

Another way the PIL spreads the message is through acquisition professionals who are on detail from DHS component agencies. Correa said this is another way to expand the number of coaches across DHS.

The PIL created a Digi-badge program in 2017 as a micro-credential that recognizes members of the DHS acquisition workforce for their innovative achievements. The PIL says in 2020 187 acquisition professionals — 49% of whom were GS-1102 contract specialists — earned their first PIL Digi-Badge. Since 2017, DHS acquisition employees earned 1,340 Digi-badges, with employees from the Coast Guard, FEMA and the Customs and Border Protection directorate earning the most.

“These change agents at the operational level are steering improvements across the procurement process,” the annual report stated.

Some of those innovations the PIL has pushed forward are more pragmatic than groundbreaking like reverse industry days or applying a downselect process to procurements.

“The downselect process is part of the Federal Acquisition Regulations. It’s been there and you could do a voluntary or you could do a mandatory downselect, or what people like to call it, ‘go/no-go factor.’ What we’ve done is taken it to the next level so that you get the vendors that are not qualified or not likely to receive award out of the process early so they can go off and do other things,” Correa said. “It costs industry money to bid on contracts, so let’s not make them waste their time, because that’s what leads to frustration and that leads to protests.”

She said the other innovation is around how the PIL communicate with vendors both before the release of a solicitation and during the bidding phase of a solicitation, including proposal evaluation.

“We also looked at how we evaluate proposals. Whether you saw a sign or a color ratings or other ratings, we talked about confidence levels like high, medium and low,” Correa said. “What we did was really focus on doing things differently, taking certain risks, and working in conjunction with, not only with the contracting officer, but also the legal counsel and the program officials and industry.”

Correa said she has heard industry and other critics about some of the efforts by the PIL, most specifically about the use of reverse industry days.

Some have said DHS just uses these events for show, but not enough changes.

Correa pushed back against those criticisms.

“If we weren’t listening, we probably wouldn’t have as many industry engagements pre-solicitation as we do today. We’d have quite a few because we’ve been listening to the industry. We wouldn’t be publishing our procurement schedules and updating them to industry if we weren’t listening,” she said. “What you hear from some of these folks is about their particular area, if they’re dealing with a particular segment or group of offices, and maybe that group doesn’t feel comfortable taking those risks. But here’s the thing, I’m not going to force it down people’s throat, you do not force innovation, you invite innovation. You support it, you nurture it. You invite it, but you don’t force it. The moment you force it, it’s not innovation anymore.”

In 2021 and beyond, the PIL plans to continue to support and nurture innovation. It says its goals include adding more employees to keep up with demand, developing a knowledge management system, creating government-industry boot camps and launching a coach-the-coach program for acquisition experts across the government.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED