Reforming federal hiring: Does the Chance to Compete Act promise more than the government can deliver?

The massively bipartisan Chance to Compete Act aims to modernize federal hiring — but experts say limitations in HR offices could stunt its potential, while...

Long considered complicated and time-consuming, and with well over 100 different hiring authorities, the federal recruitment process is finally positioned for a much-needed transformation.

But without the right investments in time, resources and staffing, agencies will struggle to expand small-scale successes from the last few years.

For years, if not decades, presidential administrations and Congress have tried to get creative, finding loopholes and other piecemeal ways to weave through the government’s convoluted, red-taped process for hiring new employees — the reason agencies have so many hiring authorities in the first place.

Recently, shared certificates have become a favorite in federal HR shops because they let staffs quickly get their hands on a list of qualified applicants. Others have focused on involving subject matter experts (SMEs) to help get the right person in the door. And still others have tried to broaden applicant pools by focusing on candidates’ skills rather than their education.

They’re all strategies agencies have used time and again — and in many cases, they work well. The efforts have transcended administrations and become successful pilots at the State Department and General Services Administration.

On Capitol Hill, a bill that’s been floating in Congress for a few years — the Chance to Compete Act — seems to encompass all of it. Under the legislation, subject matter experts would have to conduct resume reviews. Agencies would no longer rely on self-assessments to decide if an applicant is qualified. More emphasis would go toward hands-on skills.

The bill merges several modern recruitment strategies — and it’ll take a congressional push to scale the hiring practices quickly, said Rob Seidner, a former Hill staffer who first drafted the Chance to Compete Act and former senior career leader in federal human capital policy at the Office of Management and Budget. Good ideas can happen without a law, he said, but as many agencies struggle just to stay afloat with hiring, the Chance to Compete Act would propel them to have to change.

“What this will do is give notice to agencies that they must start doing this now,” Seidner said in an interview. “You have permission to use skills-based hiring, start training your HR, start training your managers, start looking into different options. Without this level of explicit congressional mandate, it’s not going to happen, because there’s so much confusion in the field.”

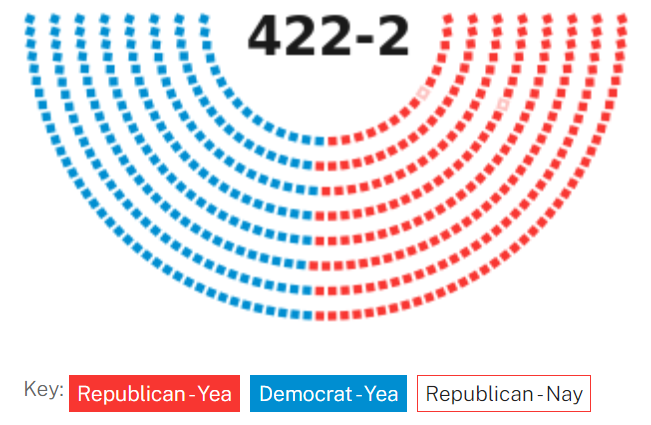

Last Congress, the Chance to Compete Act made significant progress, clearing the House and advancing out of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee (HSGAC). Although it gained bipartisan support in both chambers, the legislation did not pass by the end of 2022.

Lawmakers quickly threw their weight behind this year’s version of Chance to Compete, first introduced in both chambers in January. The House, frequently mired in partisan politics, passed the bill in a vote of 422 to 2 near the start of 2023. HSGAC is expected to mark up the Senate’s version this fall.

And it’s not surprising that groups including the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association (NARFE), the Senior Executives Association, the Partnership for Public Service and more have lauded the Chance to Compete Act’s promise to provide common-sense steps to improve practices and increase efficiency.

“Current federal hiring processes are stifling the government’s ability to bring in the talent necessary for it to effectively serve the American people,” NARFE National President William Shackelford said in a letter earlier this year. “The changes laid out in this bill work toward improving federal hiring.”

All told, the Chance to Compete Act sounds like a solid solution to decades-long complications in federal hiring — and no one really seems to disagree with the legislation’s goals.

But at the same time, the executive branch is already implementing many of the bill’s provisions. An executive order from the Trump administration urged agencies to focus on skills over education. After the Biden administration upheld the order, OPM issued guidance to agencies on how to implement it. Many agencies already use shared certificates and have repeatedly piloted the involvement of subject matter experts.

So, if agencies are already doing the work, what’s the point of putting it through Congress, too?

Jason Briefel, director of policy and outreach at the Senior Executives Association, said the Chance to Compete Act sends a bigger message about the future of federal recruitment.

“While it’s great that it’s in the executive order, this provides a lot more stability,” Briefel said in an interview. “If it’s in the law, it can prevent backsliding and it can give the sense that Congress wants to position the federal government as relevant in the broader economy.”

A bigger emphasis on skills-based hiring

Skills-based hiring has received a lot of recent attention and it’s a pillar of the Chance to Compete Act. If the bill is enacted, agencies would have to review federal positions that have educational requirements to ensure those requirements are necessary. In some cases, like certain scientific and technical positions, a degree is certainly critical, but there is a larger push in the bill toward skills-based hiring for other roles.

It’s something that could be especially useful for mission-critical or difficult-to-fill positions, including in cybersecurity, where many experts learn crucial job skills outside the classroom.

Under the bill, OPM would also be tasked with creating and maintaining an online tool listing job duties that necessitate minimum educational requirements, along with evidence to back up the need for those requirements.

But the concept of focusing on skills rather than education isn’t new. The Trump administration’s executive order created a stronger focus on skills-based hiring, aiming to broaden the applicant pools and bringing in more qualified candidates.

Still, former Hill staffer and OMB official Seidner said, the language of the Chance to Compete Act doesn’t go far enough to promote skills-based hiring.

“The Chance to Compete Act doesn’t change the minimum qualifications or classification standards,” Seidner said. “Even if assessments change, there will still be OPM requirements that disqualify applicants who lack traditional education or years of experience but can demonstrate they have the specific skills to do the job.”

Take state governments for example. At least 10 have already fully adopted skills-based hiring for their civil services. Most recently, Connecticut passed a law in July requiring the state government to broaden the definition of qualified applicants to include those without college degrees.

But in the federal government, that’s not always the case. The Air Force, for one, is looking to hire more IT specialists, but the position descriptions don’t fully embrace the idea.

“If you look at the job announcement, it still mentions 24 semester hours in specific IT courses from accredited colleges,” Seidner said. “It doesn’t allow certification from places like Google or Amazon, let alone just basing the hire on an actual IT test.”

Using subject matter experts in federal recruitment

Subject matter experts are central to the Chance to Compete Act. The bill focuses on bringing in SMEs early to better assess the quality and fit of candidates. The idea is to create a partnership between SMEs and HR staffs to select skills and how to assess them — and then use that in structured resume reviews, interviews and other assessments.

It’s not a revolutionary idea. Many agencies have already tried it through Subject Matter Expert Qualification Assessment (SMEQA) pilots, for instance, at the State Department, the U.S. Digital Service and the Department of Health and Human Services.

The goal of the Chance to Compete Act is to make SMEs an integral part of the hiring process. It pushes agencies toward using SMEs for technical reviews to determine what the department needs, what skills they’ll be able to develop and which candidates best fit those goals, said Jenny Mattingley, vice president of government affairs at the Partnership for Public Service.

SMEs have always been allowed to be a part of the hiring process, but without requirements, it doesn’t always happen.

“Congress has said, ‘we want agencies to look into doing this as more of a general rule, versus just these one-off times in hiring,” Mattingley said in an interview. “It shifts the focus to really thinking about this as a standard way of hiring versus either a pilot or just because somebody’s done it before.”

It’s additionally important to bring in SMEs before the HR office gets to its final list of candidates, Mattingley added. SMEs should help HR create that list.

At HHS, the SMEQA pilot was an “incredible” learning experience, said Bob Leavitt, the department’s chief human capital officer.

“It’s really to our shared benefit to involve more subject matter experts into the process,” Leavitt said in an interview. “And as we have done that increasingly so, we also start to see the advantages of that process.”

HHS has 10 HR centers supporting a total workforce of about 90,000 employees. At headquarters, the department’s HR Shared Service Center is experimenting with how to increasingly involve SMEs in hiring. Currently, there are three pilots at HHS using SMEs to hire IT specialists, IT program managers and data scientists. For HHS, size is an advantage.

“We can actually work across the department, across its many operating divisions, to leverage SMEs,” Leavitt said.

Most notably, Leavitt said, using SMEs helps ensure the agency gets the right candidate in the door in the first place — someone who has the right skills and is more likely to stay with the agency for a longer time.

But despite the benefits, SME pilots have revealed challenges with sustainability.

“To be brutally blunt, it’s the availability of time,” Leavitt said. “Subject matter experts are also fulfilling their mission and advancing mission. It is honestly challenging to balance those time requirements … We still have that fundamental challenge of ensuring that we are postured such that we do have the SMEs available for hiring, given the balance and workload that is required to do that.”

Using SMEs also works better for some components than others. At HHS’ Administration for Children and Families (ACF), for example, there’s often a pressing need to hire between 100 and 200 people on very short notice. The SMEQA process is helpful, Leavitt said, but more difficult for ACF because of the quick turnaround.

Beyond SMEs simply having time to participate, there’s also work on the front end to ensure they understand the guardrails of recruitment.

“It requires us to take time to sit back down with the hiring managers and the SMEs to provide the necessary training and context about the hiring process, the basic procedures and rules associated with the hiring process, as well as broader types of contextual information — everything from understanding implicit bias, to really honing in on the skills and experience of the individual,” Leavitt said.

Still, federal HR experts have said using SMEs will prove useful in the long run, especially for highly critical roles.

“With cybersecurity professionals and data scientists, your human resources staff might not know the ins and outs of whether a certain experience is relevant for the job,” SEA’s Briefel said. “It is added work. But if we don’t get it right on the front end, then you have an employee who’s not being set up for success.”

One way agencies could address that challenge is through pooled hiring actions. Pooling hiring and using shared certificates can help agencies pull from a broader number of SMEs and therefore have a greater chance of finding experts who have time to help with hiring.

“It is that partnership that is absolutely key to identifying what the hiring requirements are, but also which subject matter experts are going to be available to participate in this process,” Leavitt said.

Also, larger agencies generally have more resources to leverage SMEs. As a requirement for every agency under the Chance to Compete Act, it’s possible smaller agencies would run into trouble.

One agency CHCO, speaking anonymously to be able to comment candidly on pending legislation, said that after seeing all those requirements, subject matter experts don’t always want to get involved, either.

“Once they realize how labor intensive it is, they don’t want to participate,” the CHCO said in an interview.

It makes the lift especially heavy for HR offices, who already struggle with governmentwide skills gaps, outdated technology and limited funding.

“The other thing people need to remember is, while all this is going on, HR is not only coordinating the activity between the hiring managers and subject matter experts, they’re answering questions that are coming in from candidates,” the CHCO said. “We’re just throwing all these solutions out without saying, ‘Let’s take a pause here and figure out what the problem really is.’”

And what is that problem exactly? Strategic human capital management — an item that has remained on the Government Accountability Office’s high-risk list for more than 20 years. Looking more fundamentally at strategic human capital management, more stable funding for HR offices and strategies to fill in skills gaps with qualified employees or training are key, the CHCO said.

Using more shared certificates, pooled hiring actions

Sharing certificates, an increasingly popular tactic in agency HR offices, is another way to modernize recruitment. With shared certificates, agencies that make a hire can then give their list of un-hired candidates, already determined to be qualified for a position, to another agency. By skipping some early steps in recruitment, that second agency in theory has an easier time finding a high-quality match for a similar position. Removing some of that work from the process can give HR more time to dedicate to other areas and speed up the process, which on average takes close to 100 days governmentwide.

Of course, some positions are specific to an agency, but many do have significant overlap. For agencies, it’s an “economy of scale,” former Hill staffer and OMB official Seidner said.

“There are about 40,000 HR positions, tens of thousands of contracting positions, IT positions, inspectors and facility management,” Seidner said. “The number of positions that are truly super unique, that only one agency has — it’s pretty few.”

And that’s not all — shared certificates can benefit applicants, too. It saves time on applications and can create more opportunities they may not have had otherwise. From the applicant’s perspective, they are put on the table for multiple openings across agencies, even though they filled out just one application. That can also diversify applicant pools.

“If you’re talking about someone who’s already a low-income parent, trying to raise kids, help your parents or work a manual labor job, you may not be at a computer or may not even own a computer or have much access to one. If you have to go to the library, or borrow someone’s computer to apply for each job, you’re not going to have the ability to keep hitting apply,” Seidner said.

Agencies have been able to share certificates for years. The 2015 Competitive Service Act gave agencies the authority to share their lists of candidates.

“That was really the first step to enabling agencies to be able to share certificates,” the Partnership’s Mattingley said.

OPM published regulations on how the process would work in 2017 — along with guidance in 2018. Under the regulations, OPM determined the initial job posting had to specify that candidates would be shared later on, and applicants had to opt in to be able to have their resume shared if they didn’t get an initial offer. OPM also said each agency interested in receiving a list of candidates would get the list independently of other agencies.

Even though Congress passed the law to make it an option for agencies, it wasn’t a way that agencies were actually hiring. The practice slipped through the cracks for years.

“Nobody was thinking about it,” Mattingley said. “I don’t think it was on people’s radars.”

More recently, shared certificates have gained at least some traction. In 2022, GSA piloted the use of shared certificates in collaboration with HHS for acquisition positions. The practice is useful, HHS’ Leavitt said, but still involves a lot of work and sifting through sometimes tens of thousands of resumes.

The workload can be challenging for HR offices, many of which have small staffs and are under-resourced.

“You need to have enough people that are dedicated to doing the certificate that way, making sure the job announcements are written — and you also are reaching out to other agencies,” one CHCO said. “That gets back to the idea that offices are small, they’re just trying to take care of their own, let alone have enough bandwidth to work with other agencies. Then the other agencies have to be secure enough and interested enough to trust that another agency is running the competition the right way.”

Still, there’s room to scale usage governmentwide, and the Chance to Compete Act aims to set the use of shared certificates as a precedent. The legislation would, in theory, make it easier to share certificates and make it more of a baseline. It’s a show of congressional intent that agencies must recruit together.

The Chance to Compete Act requires OPM to create and manage an online platform for sharing certificates, as agencies request them. OPM would have to work directly with the CHCO Council to develop a plan for establishing that online tool. The legislation also tells the OPM director to “maximize” the sharing of applicants among agencies.

OPM can also initiate governmentwide pooled hiring actions. Distinct from sharing certificates, pooled hiring efforts use one job announcement to recruit for similar positions across multiple agencies.

Some recent successful examples of pooled hiring came from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, known commonly as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL). Under the BIL, OPM partnered with CHCOs from seven different agencies and hired roughly 5,000 federal employees nationwide. The new hires have gone into over 90 different positions with many using shared certificates. In one example, the Agriculture Department hired 39 HR specialists off a single certificate.

“We’ve seen more pooled hiring actions, but we haven’t seen a lot of certificate-sharing yet. This bill tries to address some of those issues,” Mattingley said.

Earlier this year, USA Jobs also launched a “talent pool” function to let agencies “quickly see if there are available certificates of eligible candidates from which they can make a selection and share talent across government,” according to a President’s Management Agenda progress update.

Now, Congress wants to make these practices the standard. Under Chance to Compete, OPM would have to host pooled hiring actions “to increase the return on investment on high-quality pooled announcements,” the bill states. There would also be a “federal talent team,” housed within OPM, for facilitating pooled hiring actions across agencies.

Moving away from self-reporting questionnaires

Another Chance to Compete Act provision attempts to move agencies away from using self-assessments — questionnaires on job applications that agencies often rely on to decide who’s qualified for a position. Self-assessments can present problems in the hiring process, such as producing inherent bias.

“Depending on how you answer those self-assessment questions, only the top people are really going to be viewed,” Seidner said. “With that test, which frankly, you can lie on, you can figure out how to game it to be top-ranked. When it comes to self-assessments and resumes, women and minority groups are more likely to under-mark themselves, if they don’t feel that they can do something — and they also don’t want to look too arrogant.”

In contrast, on its website, OPM said self-assessments are “an efficient and effective way to screen and evaluate applicants.”

“This assessment type is firmly grounded in the duties of the position and lets candidates identify their relevant experience,” OPM’s website states. “Self-report questions are carefully developed to identify specific behaviors, education and experience that will separate good candidates from great ones.”

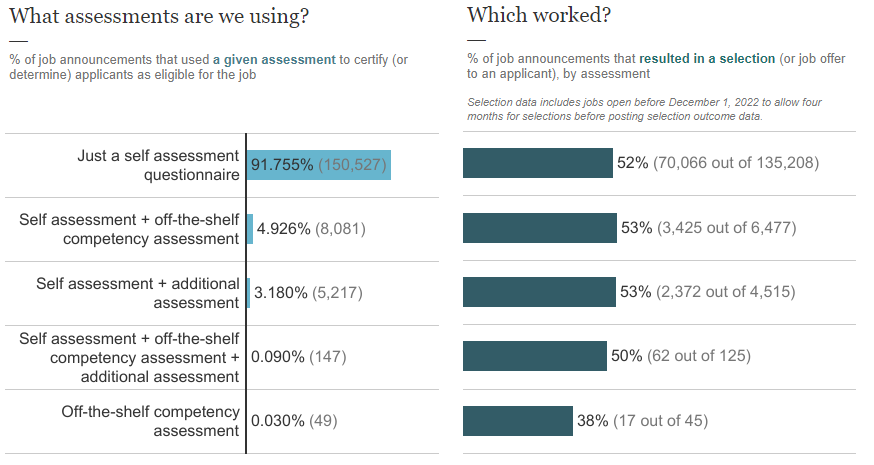

But the value of self-assessments comes into question when looking at how many candidates actually get hired. Across government, 92% of competitive, open-to-the-public job announcements relied solely on applicants’ answers to a self-assessment questionnaire and an HR resume review.

Of those instances, just half actually resulted in a hiring manager moving forward with selecting an applicant, according to a dashboard from GSA and OPM.

“When announcements did not result in a selection, 14% of the time a job offer was made to someone who applied to a ‘twin’ announcement, posted at the same time and often reserved for current and former federal employees,” the dashboard said.

OPM and GSA initially saw the dashboard as a way to help agencies comply with the executive order from the Trump administration, encouraging agencies to remove self-assessments and evaluate job applicants based on skills needed to succeed on the job.

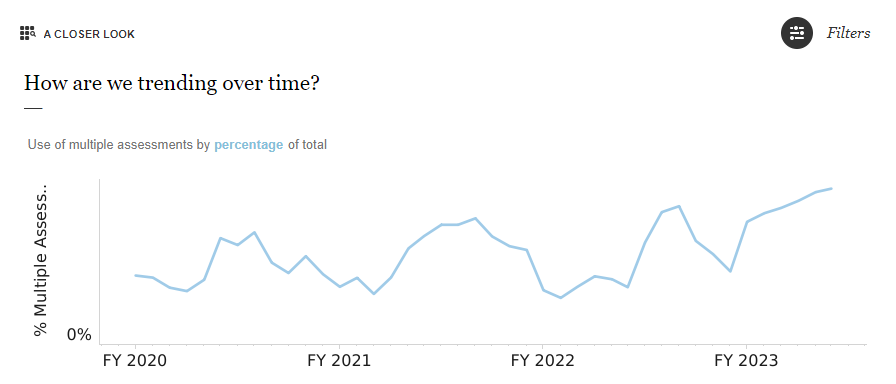

And there has been some momentum over time, with more agencies at least beginning to use multiple assessments for job applicants.

Going beyond encouragement, though, the Chance to Compete Act says agencies should use technical assessments to evaluate job-related skills, determine a candidate’s fit and rank candidates. Agencies would also be able to share their assessments with others and OPM would be responsible for creating a platform to share assessments.

The Chance to Compete Act would also push agencies toward using SMEs for technical reviews, resume reviews and other assessments to determine both what skills the department needs and which candidates best fit those goals.

“It seems hard to justify going back to the old system, which we know does not work,” SEA’s Briefel said.

It’s all aiming to make the hiring process a little smoother and faster, and even bypass a couple of steps in the process, where possible. But of course, it’ll take resources and work to make this massive shift away from self-assessments.

“To fully adopt using an additional assessment, agencies may need to develop and validate new assessments; retrain or hire staff; integrate subject matter experts and update IT systems to better track assessments and assess applicants,” the dashboard said.

Implementing Chance to Compete will require investments

After decades of agencies battling challenges in human capital management, carrying out these ideas will be a massive undertaking. Along with strategic human capital management’s 20-plus-year spot on GAO’s high-risk list, there remains a governmentwide skills gap for HR specialists — meaning agencies are generally struggling with both the number of employees and actual skills in that field.

At the same time, GAO found in a report earlier this year, OPM is at “significant risk” of being unable to help agencies address governmentwide skills gaps if it can’t first do a better job of addressing internal skills gaps. Adding to the issue, OPM doesn’t have a clear action plan to address those specific skills gaps.

Part of the problem also stems from the lack of consistent leadership at OPM. The agency hasn’t had a Senate-confirmed director serve a full four-year term since 2013. Current OPM Director Kiran Ahuja has been in her position for just over two years, but at her one-year mark in office, she became the longest-serving Senate-confirmed director since 2015.

“This leadership void had a ripple effect across government,” Partnership for Public Service Executive Vice President James Christian Blockwood told Federal News Network in March.

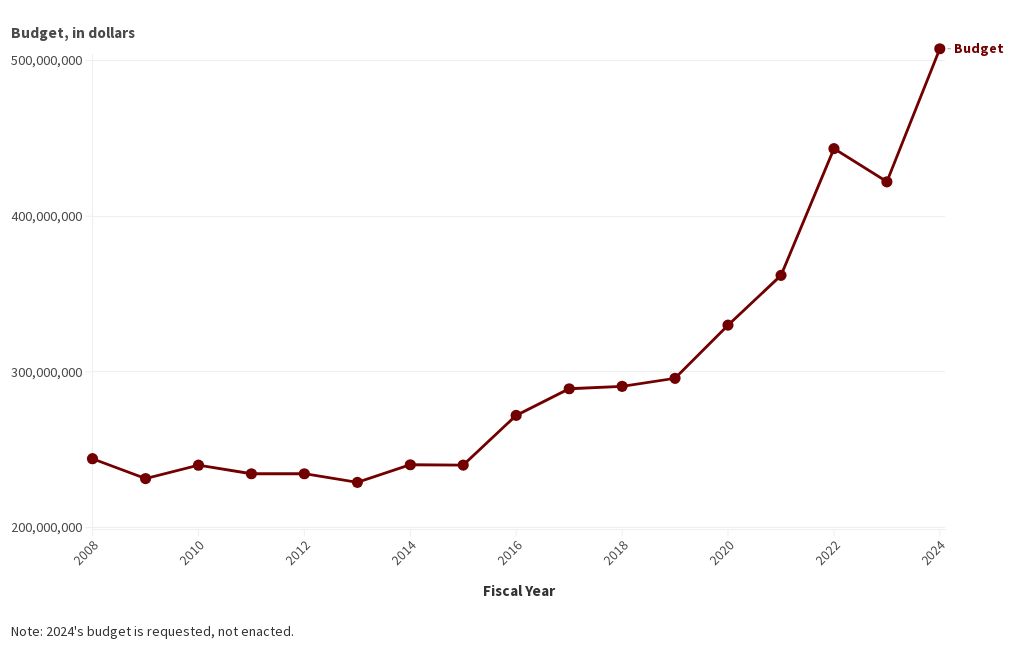

Similar to many agencies, OPM also faces funding challenges that could interfere with its ability to deal with these issues.

In fiscal 2023, OPM received $422 million in congressional appropriations. The year before, Congress appropriated $373 million and OPM got an additional $70.5 million from the Postal Service Reform Act.

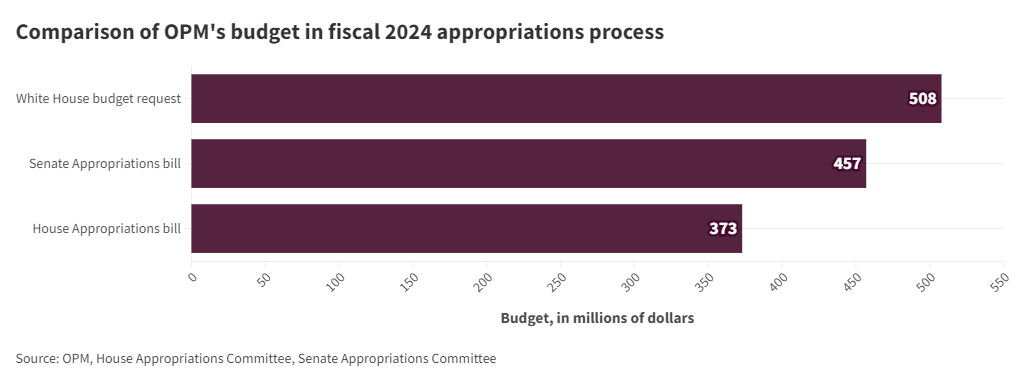

For 2024, the House Appropriations Committee wants to cut OPM’s budget down to 2022 funding levels, $373 million. And that further threatens the agency’s ability to address many of these reforms, leaders at NARFE warned in July.

“OPM needs to have solid funding and appropriated dollars that allow it to be properly staffed and to provide the oversight duties, the policy, everything else that’s related to running a large-scale, human capital operation for the United States’ largest employer,” one CHCO said.

Among the current numbers being tossed around, NARFE Staff Vice President for Policy and Programs John Hatton said the final budgeting number for OPM in 2024 is most likely to lie closest to the Senate’s proposal.

“The Senate bill was approved with a unanimous, bipartisan vote out of the Senate appropriations committee, and as part of a set of appropriations bills with total funding based on the spending caps set by the bipartisan debt limit agreement,” Hatton said in an email. “The Senate’s allocation of the total spending caps under that agreement must still be negotiated with the House — and agreed to by the full Senate — but they at least fall in line with the controlling agreement.”

On the other hand, Hatton added, “the White House budget request was its opening salvo in negotiations, prior to that budget agreement. The House Freedom Caucus continues to demand lower nondefense spending, despite the budget agreement, and has forced the House Republican caucus to pass bills out of the appropriations committee that spend below the negotiated caps. Unfortunately, those demands may threaten a shutdown. But if history is any guide, while the demands may lead to TV appearances and campaign cash for proponents, billions of wasted taxpayer dollars and ruined vacations and interrupted services for American citizens, they are very unlikely to change the ultimate outcome of negotiations.”

For now, OPM’s 2024 funding remains up in the air, but governmentwide, the Chance to Compete Act represents a fundamental mindset shift in federal HR. Still, it’s unlikely to see fruition without better investments.

“Human resources professionals in the federal government have been left behind. We don’t train these people, we don’t invest in them — and yet we keep thinking that it’s a great thing to constantly be pouring flexibilities on their head,” SEA’s Briefel said. “The flexibilities are more of a burden than a benefit if you don’t have the wherewithal to use them. The Chance to Compete Act is great, but we’re going to have to actually be able to implement it, or it’s just going to be another reform that sounded good, but didn’t really deliver because we thought the job was done when we passed the law.”

Federal recruitment is no longer just the responsibility of HR staff to recruit at agencies. Thinking of federal hiring as a team effort will aid the overall process.

“Hiring is part of everybody’s job, but it’s still time-consuming,” the Partnership’s Mattingley said. “If you’re going to bring in subject matter experts, if you’re going to run assessments, and you have this great list of candidates, it’s a shame to leave that talent on the table.”

Leavitt added, “Hiring is a shared responsibility — it is a shared accountability. As leaders in the HR space, and in broader operations, we all must be modeling and practicing the behaviors to support our teams, to advance mission collectively, in support of one another.”

Nearly Useless Factoid

A cough can travel as fast as 50mph, while a sneeze is often faster than 100mph.

Source: American Lung Association

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED