5 years later, MSPB releases results of federal sexual harassment study

Close to a quarter of women employees at federal agencies have experienced sexual harassment, according to a report from the Merit Systems Protection Board. But the...

When the Merit Systems Protection Board had to pause many of its statutory responsibilities during five years without quorum, agencies saw a long absence of the board’s comprehensive studies on the implementation of federal merit system principles.

Now, after regaining quorum, MSPB has published the first of many of these long-awaited, nonpartisan reports. Specifically, the board’s December publication dove into the prevalence of sexual harassment in the federal workforce. But MSPB collected the data for the report about six years ago.

MSPB was in the middle of putting together the sexual harassment study back in 2017, when the board first lost quorum — and therefore the board was statutorily prohibited from publishing it, as well as from issuing decisions on federal employee appeals cases.

MSPB Chairwoman Cathy Harris said although the sexual harassment report is several years old, the information within it is still highly significant for agencies and federal employees to have.

“This represents a very long-term perspective, and we thought we should continue to provide that historical perspective — that’s why we wanted to release the survey,” Harris said in an interview with Federal News Network. “It also captures employees’ opinions at a particular point in time.”

According to the report, federal employees are now less likely to experience sexual harassment compared with 20 years ago, and even more so since the board’s first-ever report on sexual harassment, dating back to 1980. Although cases of sexual harassment have scaled back, the numbers are still “unacceptable” — agencies need to do more to both prevent it, and handle it when it occurs, the report said.

The findings came from a survey that MSPB conducted in 2016, making the data now more than six years old. But according to the findings of the report, approximately 14% of federal employees experienced at least one form of sexual harassment between 2014 and 2016.

The gender disparity is greater, though, with women being more than twice as likely to experience sexual harassment. Notably, 21% of women and 9% of men have experienced sexual harassment in a federal workplace.

“The single greatest risk factor for experiencing harassment is being a female,” the report said.

“Other risk factors include the gender composition of the work unit being heavily skewed — especially for women — being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) — especially for men — and being young,” the report added.

Sexual harassment can take many forms. But for the federal workforce, the two most common, according to the report, were exposure to sexually oriented conversations and unwelcome invasion of personal space.

The exact percentages also depended on the individual agency. Agencies above the average governmentwide percentage of women who have experienced sexual harassment, which is 21%, were the Department of the Navy (27%), the Department of Veterans Affairs (26%), the Department of Homeland Security (25%) and the Office of Personnel Management (22%).

Additionally, agencies more than 2% above the average governmentwide percentage of men who have experienced sexual harassment, about 9%, were DHS (15%), VA (14%) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (13%).

“Agencies should be carefully examining what is going on in their agency,” Harris said. “Compare that to other agencies, compare that to other components of their own agency, and try to drill down and see, ‘Do we have a problem? Is the problem on our policy end? Is the problem people’s lack of knowledge about how to report? Is our problem that once people report, they’re not getting effective results?’”

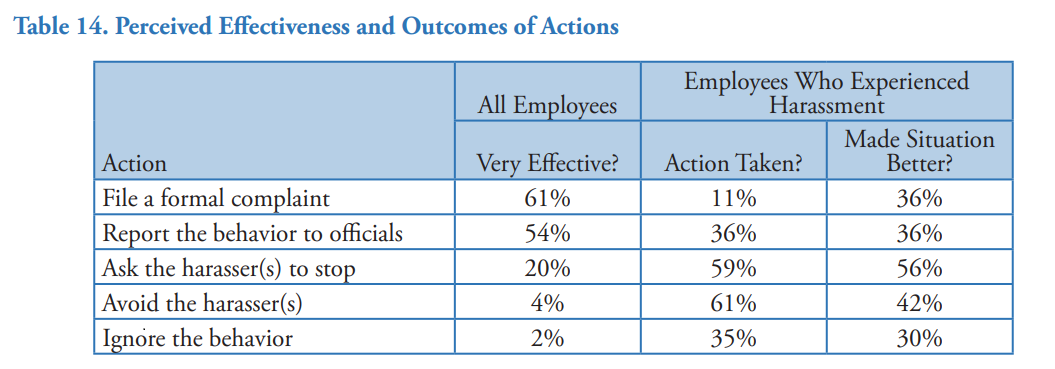

According to the report, many federal employees who experience sexual harassment often don’t take action because they don’t think it would change the situation, or in some cases, think it could make things worse. If they do decide to act, federal employees more commonly take informal routes of addressing the situation, such as asking the harasser to stop, rather than filing a formal complaint.

“To me, that means that the avenues of reporting are not resulting in effective corrective action,” Harris said.

To give employees more confidence in the process, Harris said agencies should ensure they have adequate funding set aside for dealing with these cases, and they should take corrective action promptly once an employee files a report.

The formal governmentwide process for resolving a sexual harassment case is also quite extensive. The average time it takes — from the first day of an employee filing a case, to fully implementing the orders from a decision made by an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission administrative judge — is 1,336 days, or about three and a half years.

“No one should have to wait three and a half years, or anywhere near that time, to get relief from sexual harassment,” Harris said. “That’s not what the statute anticipates, and that’s just not good business. That’s not the way to retain good employees, and that’s not the way to manage your workforce.”

Harris said the lengthy process is largely an issue of the resources that are available to handle the cases. Agencies need an adequate number of people who are conducting investigations on these cases.

“They need to be thinking about the length of time it takes and doing everything they can to expedite it,” she said.

Harris added that resolving sexual harassment issues at earlier, informal stages will help agencies better manage their often limited resources.

Agencies should “provide adequate, early, thorough, complete investigations, so that they can do the right thing as quickly and promptly as possible, which is what the law requires — prompt and corrective action,” Harris said.

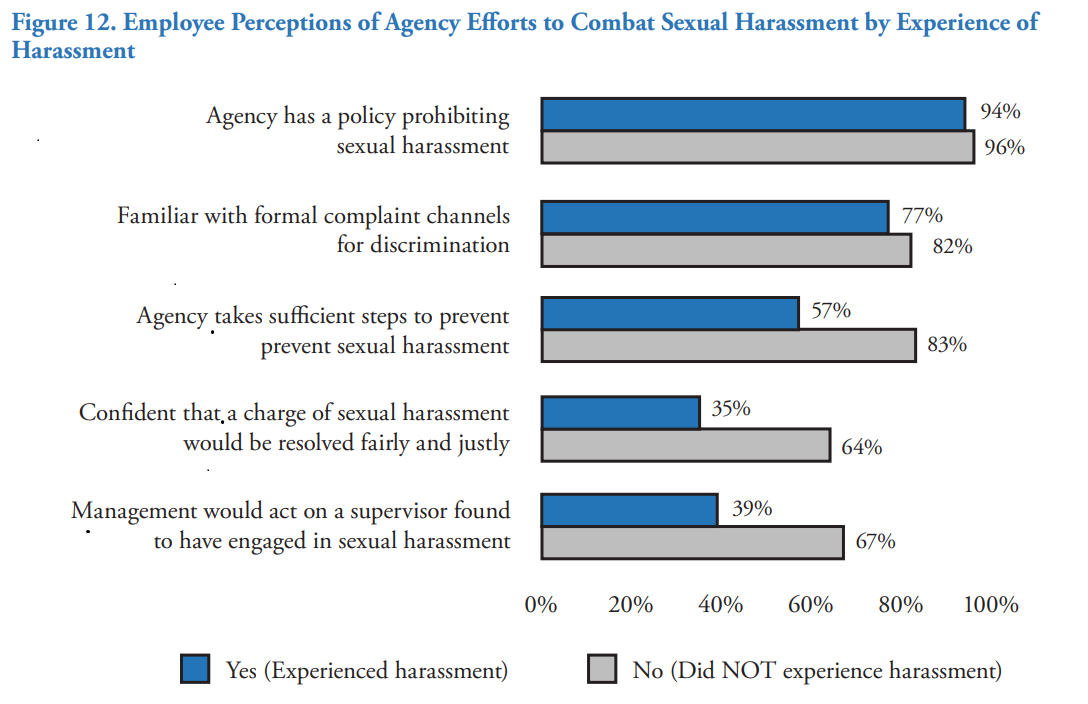

Additionally, there’s a contrast between how employees view their agencies when broken down between those who have actually experienced harassment, and those who have not. Federal employees who have been through the process are typically less confident in it, according to the report.

For example, 64% of those who had not experienced sexual harassment said they were confident that a charge would be resolved fairly and justly. In contrast, just 35% of those who had experienced sexual harassment agreed with that statement.

“When federal agencies do a good job of investigating matters fairly, and then that’s followed up by agency leaders actually taking the appropriate action, that is hugely effective,” Harris said. “I think there are breakdowns in the processes, both at the investigative stage and at the corrective action stage. Employees need to feel more confident that the agencies will be following through.”

Will the numbers change?

This MSPB report was the fourth sexual harassment report that the board has conducted and published on the topic. The first report on the topic dates back to 1980.

Notably, the MSPB collected all the data contained in the report prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the workplace has largely changed since then, with many agencies now operating with hybrid workforces — a mixture of in-office, teleworking and remote employees — sexual harassment has remained largely prevalent, Harris said.

“We know from our research that the phenomenon of sexual harassment is still being perceived by federal employees at work,” she said. “The impacts of sexual harassment on employees, the organization and mission accomplishment are persistently negative.”

The board plans to release a sexual harassment report with more recent survey data from 2021 in the coming months.

Harris noted that it may not be surprising to find that these upcoming results will be largely similar to data in the current report, with data going back to 2014.

What agencies can do

The report gives several recommendations to agencies to try to reduce, and ideally eliminate occurrences of sexual harassment.

“Frankly, [the recommendations are] pretty obvious, but it’s worth reminding,” Harris said. “We feel that they would be effective.”

For instance, agencies should communicate fair and effective policies, and codify anti-harassment language in their policy documents, the report said. There should also be clear, comprehensive and ongoing training for employees about preventing sexual harassment.

Beyond that, agency leaders must also act as exemplars of a workplace culture that doesn’t tolerate sexual harassment, including in virtual workspaces. Modeling good behavior from the top down, Harris said, is “hugely important.”

“[Leaders should] show employees, ‘we don’t just care, we’re not just giving you training, we’re actually following through when there are violations of our policy, we’re doing the right thing,’” Harris said. “That says a lot and that helps the next employee who comes along with a complaint.”

Beyond this sexual harassment report, MSPB has published a research agenda detailing its publication plans going through 2026. One of the reports coming up first will be an update on the prevalence of prohibited personnel practices at agencies, a long-standing area of focus for the board.

MSPB making headway through backlog

Restoring quorum for the MSPB meant more than just being able to issue these types of reports. It has also meant MSPB members can resume work to reduce a large backlog of federal employee appeals cases by issuing decisions.

At its peak, the case backlog was around 3,500 last March, just before MSPB restored quorum. Since then, the board has issued decisions on more than 800 cases so far. Of those cases, 48 have been precedential cases, including cases involving whistleblower reprisal, discrimination and backpay.

“The hope is by trying to get our precedential decisions out, that will help filter down and make other decisions more simply easier to decide,” Harris said.

Additionally, the board has issued 70 cases that involve a settlement agreement.

“[It’s often said that the] best settlement is one where both sides walk away miserable. I don’t believe that. I think there are ways for people to create settlements in a positive manner, and for both sides to be happy. That’s what we’re looking for,” Harris said.

The board also just launched a pilot program in October to more efficiently issue decisions on petitions for review (PFRs). The program, called PFR RAMP (Rapid Assessment Mediation Program) targets particular categories of appeals cases that are well-suited for rapid mediation. The pilot will target, for example, performance removal cases.

“The mediators assigned to that program have been actively identifying cases that are candidates for the program, and have already held or scheduled mediation in more than 100 cases,” Harris said.

MSPB’s goal for fiscal 2023 is to issue decisions on at least 1,000 cases, including at least 750 of the oldest cases that are pending before the board. If the board stays on track, it will take about three years to clear the backlog.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED

Related Stories