Congress not yet convinced of Trump administration’s proposed OPM-GSA merger

Margaret Weichert, acting director of the Office of Personnel Management, acknowledged Tuesday the administration may need more time to carry out the proposed...

Lawmakers on Tuesday afternoon expressed bipartisan concern and skepticism for the Trump administration’s proposed merger of the Office of Personnel Management with the General Services Administration.

And they weren’t alone.

The Government Accountability Office, OPM’s inspector general and a former agency director said the administration hasn’t demonstrated enough evidence to date to show the proposed OPM-GSA merger makes sense. They, along with federal employee groups and unions, largely disputed the Trump administration’s stated reasons for the merger — questioning whether GSA was up to the task of inheriting OPM’s beleaguered IT systems.

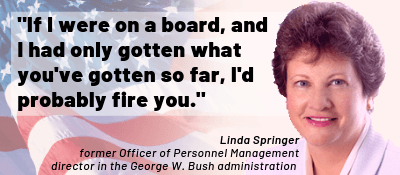

A corporate board of a business involved in a private sector merger such as this one would demand a vast variety of research, analysis and data from its CEO, Linda Springer, a former OPM director during the George W. Bush administration, told the House Oversight and Reform Government Operations Subcommittee.

Ideally, a corporate board looking at a reorganization like this proposed OPM-GSA merger would look for a cost-benefit analysis, financial implications, an inventory of statutory and regulatory impact and how those impact both GSA and OPM and any other entities, as well as labor-management agreements, integration risks and challenges and detailed migration and communication plans, Springer said.

“If I were on a board and I had only gotten what you’ve gotten so far, I’d probably fire you,” she said.

No member suggested Congress should go that far. But no one seemed satisfied by the 387 pages of documents the Trump administration provided the committee in advance of Tuesday’s hearing.

Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), chairman of the House Oversight and Reform Government Operations Subcommittee, had requested a long list of documents that detailed the administration’s plans for the OPM-GSA merger.

Of the documents the subcommittee had received, 300 covered the upcoming move of OPM’s National Background Investigations Bureau and security clearance business to the Pentagon.

Roughly 30 pages were cover letters for documents given to OPM’s inspector general but not the actual documents themselves, Connolly said. About seven pages contained copies of emails Weichert had sent to OPM employees, but none were about the proposed merger, according to Connolly.

The subcommittee also received a cost savings analysis for the OPM-GSA merger at 12:29 p.m., an hour-and-a-half before Tuesday’s 2 p.m. hearing, Connolly said.

He also described a page that was supposed to show a timeline of the administration’s engagement with Congress and other stakeholders about the OPM-GSA merger. But the page was blank, Connolly said.

“So that’s a printer problem,” Margaret Weichert, OPM’s acting director and deputy director for management at the Office of Management and Budget, said.

“A lot of that going around,” Connolly said.

“Old technology,” Weichert quipped.

“If your purpose was to demonstrate to Congress that your technology is not working well, you have succeeded,” he said.

OPM claims lack of resources spurring merger

Weichert outlined many of the same financial, structural and strategic reasons for the OPM-GSA merger the Trump administration began circulating last week.

OPM simply doesn’t have the resources or people to properly handle the mission the Carter administration originally envisioned for the agency back in 1978, she said.

“Policy headcount has been crowded over the years by competing priorities and structural issues. OPM supports $2.4 trillion in its balance sheet covering retirement, healthcare and insurance liabilities, but is supported by 6,000 employees, more than half of whom work on background investigations. Companies like Fidelity Investments with comparable balance sheets have 50,000 employees, many in IT. Notably, only 281 OPM employees do core merit systems policy work. Currently fewer than 200 feds are dedicated to the technology that supports this massive balance sheet.”

OPM is actually budgeted for nearly 300 IT employees, Weichert said, but the agency hasn’t been able to attract top talent to the positions.

Related Stories

‘Greatest risk we have is doing nothing:’ Trump administration details case for OPM reorg

“Central to a successful reform is transparency and engagement with stakeholders,” said Triana McNeil, acting director of strategic issues at GAO. “Questions like what [does] success look like? What management challenges will the reform resolve? How have Congress, employees and other key stakeholders participated in this solution? These are basic questions that GAO would have expected to be answered by this time. As of now, GAO has little to no evidence from the agencies to answer any of these.”

OPM’s acting inspector general agreed.

“I do have concerns,” Norbert Vint, the agency’s acting IG, said. “The very basic concern is the fact that we have not been given any analysis of any sort, either alternative or quantitative data that would support some of these decisions.”

Despite the criticism, no member refused to engage with the Trump administration to resolve OPM’s current challenges. Connolly said he met with Weichert earlier this week and was willing to work with her on a solution.

“I’m certainly convinced of her sincerity,” he said of Weichert. “I don’t think she has some hidden agenda. We disagree on the analysis and on the proposed solution. Hopefully [Monday’s] meeting and this hearing is the beginning of a dialogue, but our concerns are very real. This hearing, I hope, will be a wake up call. Our federal workforce is our greatest asset. Improving OPM ought to be a bipartisan goal, but revitalizing OPM requires careful planning and a clear understanding of its problems.”

Republicans also want better plan

Republican members expressed a similar desire to chart a better path forward for OPM — or whatever organization will manage the federal workforce in the future.

“This whole situation affords this committee to work together in a bipartisan way,” Rep. Jody Hice (R-Ga.) said. “We have to find a path forward that both protects the merit system [principles], while at the same time moves forward on an efficient and effective future.”

Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.), ranking member of the subcommittee, suggested the administration could be more communicative with OPM employees. He said he wanted to be sure federal employees understood the OPM-GSA merger isn’t about cutting the workforce but achieving a more effective and efficient organization.

Weichert said she and the administration have held meetings with OPM employees about the proposed OPM-GSA merger. The administration is also posting information about the plan on OPM’s internal website for employees, she added.

Weichert said she and the administration have held meetings with OPM employees about the proposed OPM-GSA merger. The administration is also posting information about the plan on OPM’s internal website for employees, she added.

Yet J. David Cox, national president of the American Federation of Government Employees, said it was leadership of AFGE’s OPM local that had called a town hall meeting with employees earlier May, not Weichert.

“Reading the body language of people in the audience, what I would ask you to do is maybe redouble that outreach in terms of stakeholders, how about that?” Meadows said.

More time needed to plot merger details

Yet what that path will look like in the short and long term is still unclear. Weichert reiterated her argument that Congress has practically no choice but to merge OPM’s remaining functions to GSA. OPM will face a $70 million shortfall when the National Background Investigations Bureau and its security clearance business transfers to the Pentagon by Oct. 1.

Weichert said she’s hopeful Congress will help resolve this challenge. It’s why the administration last week submitted a legislative proposal to lawmakers, outlining the plan to move most roles, responsibilities and authorities of the OPM director to the GSA administrator.

Weichert is banking on Congress to move with urgency, but some members suggested the administration simply needs more time to plot out the details for the OPM-GSA merger — or find another alternative altogether.

“I can understand that you’re trying to do something very difficult,” Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.) said. “You yourself are saying that many of the documents that we’ve asked for [and] that we’d have to rely on haven’t been provided to us. That means that zeroing out OPM at the end of this fiscal year would just be impossible, wouldn’t it? You need more time, at the very least.”

More Workforce News

In the meantime, members on both sides of the aisle asked Weichert to work with Congress and GAO to develop more plans and analysis for the OPM-GSA merger, and she agreed.

Springer, however, suggested at least one other organization should be a part of the conversation.

“We haven’t heard a lot about this today, but we should be looking at GSA as much as we’re looking at OPM,” she said. “What does this do to GSA? What does it do to their ability to deal with their own challenges, let alone take on an entirely new set of responsibilities?”

Connolly, meanwhile, said he and others members were prepared to work with the Trump administration to work through OPM’s challenges.

“You’ve heard a lot of skepticism, and that’s very real,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we’re not willing to be engaged. We are. Consider this the first big step in the dialogue.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED