Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Growth of bases means more creature comforts for feds

For military bases in the national capital region, forget the \"closure\" part of Base Realignment and Closure. The 2005 BRAC round means huge growth at bases a...

By Jared Serbu

Reporter

Federal News Radio

In prior years, the Defense Base Realignment and Closure process has come to be known for shutting down military bases for good. Indeed, that held true in the current BRAC round for many parts of the nation.

But for bases in the national capital region and a handful of others around the country, the 2005 BRAC round meant huge growth, not closure, and along with it, a need for new infrastructure and workforce support services on those installations.

To say Fort Belvoir in northern Virginia is growing would be an understatement. It is the largest net-gainer in terms of new personnel from the 2005 round of BRAC decisions. By the time all the moves are finished, its workforce will have nearly doubled in size. Army officials say it will soon be the fourth largest base in the continental U.S.

At Fort Meade in Maryland, the growth numbers are smaller, but BRAC has brought 5,400 new people to the base. And moves that have nothing to do with BRAC but just happen to be occurring at around the same time are adding another 7,000 personnel to Meade.

By far, the largest new inflow of personnel into Fort Meade as a result of BRAC decisions comes from the construction of a new headquarters for the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA). But to support its workforce of 4,600 and encourage them to make the move from the agency’s various locations in northern Virginia, DISA also built a number of creature comforts into its new 1.1 million square foot facility. David Bullock, DISA’s senior executive in charge of BRAC issues, said considerations relating to the comfort of the workforce went right down to the design of employee’s desks.

The agency’s old workplaces were filled with cubicles that employees referred to as “bunkers,” Bullock said during a tour the agency provided to Federal News Radio. He said the new desk walls are high enough to allow privacy, but low enough that employees aren’t cut off from their co-workers. Additionally, each workspace includes areas set aside for informal, impromptu meetings and discussions, allowing colleagues to meet and discuss issues without ducking into a conference room for hours.

“We were very concerned about reconstituting the workforce at Fort Meade, so we wanted to create a facility that would be appealing to our workers, that would be attractive, that would provide a great deal of openness, a great deal of natural lighting, and would provide a collaborative environment where people getting together to do extremely technical functions could operate with other employees,” he said. “That was one of the goals we laid out for our design-build team in designing the overall building.”

DISA builds in comforts

Outside the workspaces themselves, DISA built its own conference center and training center for more formal gatherings. It also has a 750-seat dining facility and its own fitness center with three fitness specialists and five full-time instructors, with classes on everything from Pilates to yoga to spinning to kickboxing. Employees are given three paid hours per week that they can use to exercise in the facility.

DISA also built a dedicated power supply system to provide energy to the large campus, which covers an area the size of 24 football fields. Two separate lines connect not to the rest of the Fort Meade grid, but to independent substations off-base. The agency also has backup generator and battery power systems, as well as its own backup water supply.

For the base’s management, having DISA bring its own infrastructure took pressure off of existing facilities that are feeling the strain of other tenants moving to Fort Meade under BRAC, including the Defense Media Activity, a new consolidated DoD security clearance adjudication center and other Defense components moving to the base for non-BRAC reasons.

“It’s not actually common for organizations to come in and build a fitness center inside of their facility,” Col. Dan Thomas, Fort Meade’s garrison commander told Federal News Radio’s The Federal Drive in an interview. “For instance, we’re finishing a new brigade headquarters here on the base, which has nothing to do with BRAC, but there’s no fitness center there because we as a garrison are supposed to provide those underlying service provisions.

Fort Belvoir growing by leaps and bounds.

Forty miles to the south, the growth at Fort Belvoir in northern Virginia is even more pronounced, though it’s not primarily driven by the move of any one DoD organization. Belvoir’s main post and three satellite locations will have taken in an additional 19,300 personnel by the time this year’s BRAC moves are complete. Mostly administrative, logistics and intelligence personnel are arriving from primarily leased office space around the national capital region.

Don Carr, Belvoir’s director of public affairs, said the consolidation had been a vision for the Washington area for the past 20 years, but it took BRAC to generate the budget dollars necessary to construct the buildings and the underlying infrastructure the moves would require.

“Our main drag here, Belvoir Road, has always been a two lane road,” he said. “We just recently widened it to four lanes. It’s one of three main arteries that we’re taking from two lanes to four lanes. That costs money. Our new hospital costs money. BRAC is investing $4 billion in the construction of new facilities to accommodate the jobs moving in here.”

Off-base roads are another concern. Congress only last month appropriated federal funding to widen U.S. Route 1, the main access point to the base, and construction will not begin until the BRAC moves are complete.

The new hospital, Fort Belvoir Community Medical Center, is a 1.2 million square foot health care complex that will partially absorb the functions of Walter Reed Army Medical Center, which is closing and merging with Bethesda Naval Medical Center as part of BRAC. It is slated to be ready for patients this August.

At certain points, BRAC construction activity has involved up to 150 separate projects at any given time. The work includes 6.3 million square feet of new building space, 7 million square feet of parking, and the construction of several large new buildings. The project is so large that the Army Corps of Engineers had to bring together project officers from three of its national districts to oversee and manage all of Belvoir’s construction.

Besides the hospital, large BRAC projects have included a new headquarters for the Missile Defense Agency on the main post, a 2.4 million square foot complex for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency on a satellite campus known as Belvoir North, and a 1.8 million square foot DoD office complex at another off-site property known as the Mark Center in Alexandria, Va.

As at Fort Meade, the majority of the workforce moving into Fort Belvoir is made up of civilian federal employees, not uniformed military personnel. Travis Edwards, a spokesman for BRAC issues at Belvoir, said that in addition to building new housing, commissary and exchange services for military personnel, the post was trying to improve access to quality of life services for civilians.

“When you add personnel to a military installation, the need for certain services increases,” he said. “One, specifically, is child care. This BRAC will bring five more child development centers to the post, which will really help the workforce. They’ve been spread all across the post and they’ll be opening as we get them completed.”

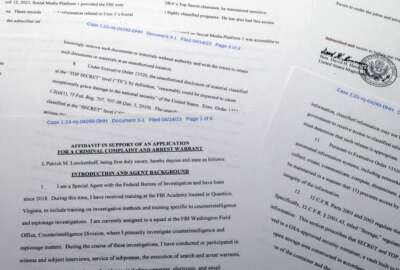

(Editor’s Note: No photos were allowed inside the Ft. Meade complex for security reasons.)

RELATED STORIES:

DISA explores options to BRAC traffic

DoD benefitting from BRAC-inspired IT upgrades

(Copyright 2011 by FederalNewsRadio.com. All Rights Reserved.)

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.