Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom starts with the notion that the federal correctional facility is the basic unit in the Bureau of Prisons. Tom's guest is a corrections consultant, who se...

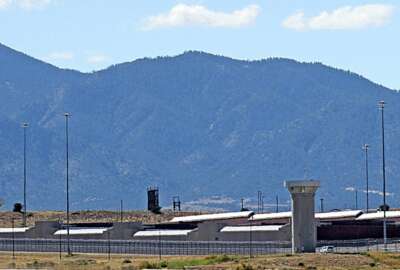

Federal Drive with Tom Temin continues his week-long series, The Worst Place To Work in the Federal Government. Because of its last place in this year’s rankings, that title goes to the Bureau of Prisons, part of the Justice Department. In today’s interview, Tom starts with the notion that the federal correctional facility is the basic unit in the Bureau of Prisons. Tom’s guest is a corrections consultant, who served in the Senior Executive Service and as warden of ADX Florence, the system’s most secure prison. The Colorado facility is also known as Super Max. For lessons learned there and how BOP can regain its footing, we hear from Robert Hood.

Interview Transcript:

Tom Temin And just briefly review your own career with the Bureau of Prisons, because you did rise to that level of warden, which is kind of field captain or field general, you might say.

Robert Hood Sure. Especially with my background, I started out as a prison teacher in the New Jersey system, state system. I went to Texas. So joining the bureau in 1981, moving up, I finally moved into the chief position right there in D.C. as the chief of the Office of Internal Affairs, and then eventually moved to several warden ships in Tucson, Sheridan, Oregon, and finally the Alcatraz of the Rockies, they call it out here in Colorado. And Janet Reno, when she was alive, she provided me my senior executive service level back in 2000 year, somewhere in that area.

Tom Temin What are the challenges in being a prison warden? I don’t think people really understand that job except what they’ve seen with Karl Malden and some old movie a thousand years ago.

Robert Hood But that’s one of the challenges, the media versus the reality. To me, it’s the balancing out of security and treatment, the two different parts of the prison, if you will. But on one hand, you’re holding them, you’re using security or shaking people down and strip searching this and that. But also you’re saying we care about you because 95% of you are coming out. So it’s it’s a balance of security and treatment. It’s holding staff and inmates accountable. The the fact that in the Bureau, I think it’s around 66,000 inmates, around 44% or so of the inmates, drug related offenses. So again, some people tend not to get into the Stockholm Syndrome, but where people are overly compassionate, that’s that’s a challenge for us. And also the introduction of that contraband coming into the prison. Technology, cell phones, drones, people trying to sneak things in, people, inmates are inmates. And as far as them wanting to get out, that’s their job, some of them, and our job is to keep them in. On the recruitment bases, it’s a gender situation. About 72% of the staff are male, 28% are female. And so we look at the diversity or the lack of diversity, trying to match the inmate population as much as possible. And unfortunately, the day by day challenges some of the institutions are in remote areas or high cost of living area that is hard to pay someone $50,000 when they’re in downtown New York City.

Tom Temin Sure. And it’s hard to get someone from New York City to move to Florence, Colorado.

Robert Hood Correct.

Tom Temin All right. And one of the corrections officers that we’ll be hearing from says that the communications have broken down between management at facilities and the rank and file corrections officers. And that’s one of the reasons that it gets low ratings in the best places to work in the federal employee viewpoint scores. What do you say to that issue? How is it different now perhaps than it was in your time?

Robert Hood We always had problems with communication. That’s just part of the system, if you will. However, I think the difference, and I concur with that individual’s comments, is that we’ve had we need consistent leadership. There’s only been 12 directors in the Bureau of Prisons since 1930 when we became a system, but we’ve had five in the last 12 years. And again, what does that have to do with communications? A lot. When you have a turnover in leadership and then we have just the lack of transparency, the fact that we have 122 prisons, 160,000 inmates and around 34,000 staff it’s a large system. So in fairness, communications are kind of tough. But on the other hand, I think in my opinion, from an outsider, looking back at the system, it seems like with the consistency and leadership less of a concern or no concern, when I was coming up through the system of what we call augmentation, that’s when correctional officers are strapped because there’s less and less working into the prison system. So we’re taking someone out of a medical field someone who’s working as a nurse or my secretary at the prison and putting him in the guard tower with a weapon. And so that kind of stuff, I think, impacts the communications because you go into work thinking I’m here to save or work with the inmates. I’m the what I said before, I’m a program oriented person. I’m a teacher like Bob Hood years ago, but I’m coming in thinking I’m going to help a guy get his GED and someone’s handing me an M-16 and saying, get in the gun tower. So those things, I think, just add up. But mostly, in my opinion, mostly it’s the need for consistent leadership.

Tom Temin We’re speaking with Robert Hood. He’s a former Bureau of Prisons warden and now a consultant in Prison Matters. And so. What do you think, the BOP, we have a new director in place and very promising person. And she’s in touch with the union, in touch with the employees, maybe getting a little bit around the middle management there. What do you think she could do to start making that a place that is more effective by making it a better place to work?

Robert Hood I’ve been to many of her prisons. She came from Oregon. I was the federal warden, the only federal warden in Oregon, and she was the director of corrections there. So I’ve been through her institutions. I’ve met her once or twice in that capacity. Just to qualify that. Right on top of the list is getting the transparency going. We need to have the public trust of us. Right now we have 122 prisons and there’s a wall there for a reason to keep the inmates out. But it’s not to keep, Tom, like a person like you asking a couple of questions out. We’re trying to trying to work it work this in a manner where we have more transparency. I think she needs to look at pushing the one, and I think she will, pushing the mission, the reentry mission. We have 40,000 inmates coming out of the federal system every year, every year, and 43% or so are going to come back. That’s a failure rate as far as I’m concerned. I think she needs to come in and I think she will come in and try to get the custody folks on the same page as the program oriented folks. Like I said before, the difference between security and treatment initiatives. So to get that banging, banging the drum to say, guess what, all staff, every single BOP staff needs to be held accountable for what we’re doing on reentry, getting these guys out and getting them to stay out. This suggestion to you and whoever, I’m sure your audience listening is, it’s not going to be popular with the Bureau of Prisons, but it’s the age retirement issue or requirement issue. Right now you can have ten years in corrections in the state system. You can knock on the door and say, hey, I’m Bob Hood, I want to join you. I have a master’s degree and I’m 38 years old. And they’re going to say, take a walk. You must be under 37 years of age to be hired by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and you must get out by 57. And so think about that if I’m about 57 now. But if the law was different, I wouldn’t be talking to you because I wouldn’t be allowed to be talking to you. But more importantly, I’d still be there. I truly would still be working for the Bureau of Prisons at my age if they didn’t say it’s time to go at 57, which is by law. So they need to look at that and perhaps the reclassification of staff. When you think about it all BOP staff are federal law enforcement officers first, regardless whether you’re a teacher or you’re a preacher or whatever it may be. So when you think about that, that’s great because when you retire you have retirement for life. And as a law enforcement officer, it was good for me. So I hate to make it less good for others, but the reality is they need to look at that. And does everyone need to be classified as a federal law enforcement officer? I’m sure Director Peters, I know she’s going to be looking at the reduction of mandatory second and third shifts unless there’s an emergency where staff member comes in to work. They have childcare needs, they have their family home they have maybe even another job to go to. And all of a sudden someone says, you need to work two shifts. Now you’re going to work 16 hours or three shifts. And you don’t know that when you came to work that day. That’s tough. That’s tough If you’re really trying to recruit people. And you can’t, and I don’t think she will, assume that pay retention bonuses. Oh, yeah, If you come with us and you stay a year, we’re going to give you a bonus and that’s going to lower staff turnover. That’s good. I’m not saying you can’t get more staff in the process. However, it’s not not as much of a benefit when you really compare to the other things I just mentioned.

Tom Temin So it doesn’t sound primarily like a money problem because they are authorized for 40,000 people. They only have 35, there’s about a six, five, 6000 person shortfall that they’re budgeted for. But on the other hand, I do hear from several quarters that they are way behind in physical maintenance of facilities, and that can be bad for both employees and the inmates.

Robert Hood Oh, definitely. If we are going to cut back and sometimes you get the phone call from the director’s office and say like, oh, 122 prisons, we need to cut back 5%. And that comes down from the hill or whatever. But there are across the board, across the government. But you’re right, we have inmates and staff working in some capacities in a 100-year-old prison. And it’s a security nightmare. It’s not fun to come to work. And then even if you have a fairly modern one we’re there’s only been three supermaxes in history, federal supermaxes. Alcatraz, Marion, Illinois and then, of course, the one here in Colorado where I was warden. But even if it’s a very modern looking prison, it’s the nature of the prison also that might turn off and have a great turnover of staff because you’re looking at 12 gun towers. When I went to work, I liked it, I like the environment, but not everyone coming to work for the first time as a teacher, preacher whatever, officer, whatever may be, likes looking at what we had, which is 12 gun towers, no view of the Rocky Mountains that are out there and inmates locked in their cell 23 hours a day, not just because they’re a bad and they’re going to be there for a couple of days, for the rest of the life. They’re sentenced to that kind of environment. So it’s it’s not for everyone. And I think when we aired The Shawshank Redemption that some of the great movies that are out there, it also makes you interested. But then you don’t necessarily want to sign up and maybe stay.

Tom Temin Yeah. Birdman of Alcatraz has a more colorful sound than Escapee from Florence, Colorado, or what the case might be.

Robert Hood Exactly.

Tom Temin But there’s hope. I mean, the agency could take concrete steps and get get out of that cellar of best places to work and maybe not be the worst.

Robert Hood Right. And it’s hard to say. Look at the map right now and look at 122 prisons. And even though they asked the staff, would you like to go here? And they pay your way sometimes for your home and everything else to transport around. I moved 13 times in my career. And maybe that’s why I became a warden. Not everybody can do that. They have friends, family, they the children in the school and stuff. And they say, no, I’ll stay where I am. So if you’re in the same location or if you’re lucky enough to say, I want to become a lieutenant, I’m a correctional officer making 50,000. I want to be a lieutenant, I want to go from Colorado right here. But they say, okay, we have a job for you. It’s in Hawaii. Well, you’re going to cut your salary in half. So you can’t think that a promotion in the bureau is really a promotion, because on paper you feel better because you moved up, but you don’t feel better when you get the paycheck because you might be going to God forbid, I shouldn’t pick on these places, but it might be L.A. or New York City or some high cost of living area where you’d be better off in so many local jobs than join the bureau.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED