Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

The commission is looking at a strategy built around deterrence through punishment. If retaliation for cyber attacks are swift, decisive, consistent and public ...

The Cyberspace Solarium Commission — a panel consisting of lawmakers from both sides of the aisle, senior agency executives and private sector leaders — plans to release its first report, along with a set of 75 recommendations, sometime within the next few months.

Those recommendations will revolve around a central theme of getting government to react more quickly and decisively in response to cyber attacks, in a new take on the decades-old concept of security through deterrence.

“The fundamental thing we’ve been grappling with is that, unlike nuclear weapons, for example, you don’t need necessarily access to nation-state resources to have access to very powerful cyber weapons,” Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), co-chair of the congressionally established Cyberspace Solarium, said Tuesday at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. “In other words, you don’t need to be a great power to have a great impact in cyber. And deterrence is hard enough when it comes to dealing with nation state actors, where the decision makers are known but yet still unpredictable. It becomes even more difficult when you’re dealing with non-state actors who may not be known and whose identities are obscure or nation states that intentionally try to obscure their activities in cyberspace.”

That’s why the commission is looking at a strategy built around deterrence through punishment. In other words, retaliation for cyber attacks should be swift, decisive, consistent and public. The idea is that clear, consistent consequences will make adversaries less likely to instigate attacks.

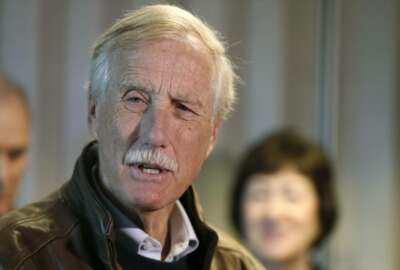

“It’s clear that deterrents at the level below the level of kinetic force has not worked. And I believe because we haven’t had a coherent deterrent strategy and that our adversaries have to understand they’re going to pay a price,” said Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), the other co-chair of the solarium. “It may be sanctions, it may be cyber, it may be indictment of their citizens. And again, if we had an international community that agreed, and we could indict somebody in one of these foreign countries and they couldn’t travel anywhere else in the world, that would really mean something because other people in the world would extradite them for this offense. So this is one of the areas that we’re working on most diligently because I believe without deterrents, we’re going to be constantly in the patching business, and that’s not going to be sufficient.”

Gallagher and King gave a preview of some of the recommendations the panel will make, to include incentivizing cyber hygiene within the private sector through cybersecurity insurance, empowering agencies to enhance their existing cyber strategies, and a more intensive use of red teaming.

The biggest struggle, they said, is building trust between the private and public sectors. On the private sector side, that means taking cyber more seriously, and being more forthcoming in reporting intrusions.

“I believe, and this isn’t insulting anybody, but I believe everybody is overconfident,” King said.

One way the panel is looking at incentivizing that level of cyber hygiene is through the creation of a cybersecurity insurance market.

“If there was a vigorous insurance market for cyber destruction, the insurance market would enforce the hygiene,” King said. “In other words, the insurance company will say to the company, ‘If you do these things, your rate will be $X. And if you don’t do these things, your rate will be $2X.'”

Overall cyber hygiene could also be enhanced through greater use of red teams, the practice of employing hackers to try to penetrate your systems as a method for finding vulnerabilities.

“I mentioned the CEO that says everything’s okay,” King said. “When a skull and crossbones appears on that CEO’s desktop and says, ‘Gotcha! Love, the Department of Homeland Security,’ that may be a way of getting their attention.”

But the public sector is not without its own share of the blame. King and Gallagher said agencies need to be more forthcoming about sharing information with industry, rather than immediately classifying everything. They said they’ve seen instances where it took four separate steps over the course of a month just to notify a political candidate that their campaign had been hacked.

Gallagher also said more widespread adoption of best practices like the 1-10-60 rule need to happen. That rule says that organizations should aim to detect an intrusion within 1 minute, analyze and evaluate it within 10 minutes, and remediate it within 60 minutes. The prevailing wisdom is that it usually takes less than five hours for hackers to achieve breakout on network operation control.

Data from this practice should also be collected and made readily available for review in the event of an intrusion so that it’s easier to determine if the incident was caused by negligence.

“The federal government can lead by example by having a better reporting process to Congress and a better oversight structure in Congress where we’re able, at least on a quarterly basis, to poke the relevant agencies and see how are we doing in cyber? Are we improving? Are we a learning organization?” Gallagher said.

But effective oversight and response to cyber incidents will require some reorganization in both the legislative and executive branches, they said.

“I think there is near unanimity on the need to have a sort of focal point within the White House to do oversight of that cyber community. Although the devil is in the details with that proposal,” Gallagher said. “And then I think there’s near unanimity on the desire to fix the problem whereby congressional oversight of cyber is disparate and divided among a ton of different committees and subcommittees, and perhaps taking inspiration from the ways in which the Select Committees on Intelligence were formed in the seventies, figuring out how we can better do oversight of cyber from Congress.”

On the executive side, Gallagher said cyber workforces need to be beefed up, starting with DoD.

“Without getting into the exact number, I think I can say that we will be requiring DoD to do a force structure assessment of the cyber mission for CYBERCOM and all the service cyber forces in the final text of the report,” he said. “And I think it’s important to note that when we took a look at the operational capacity of the cyber mission force, which is now in full operation capacity — there’s 6200 people across 133 teams — that was prior to the emergence of Defend Forward as an organizing idea within the cyber community, and prior to the emergence of a variety of threats that have now shaped our understanding of the cyber landscape. And so I think it’s fair to say that the force posture today in cyber is probably not adequate. I would go further and say you could expect the report to have a variety of recommendations concerning how we enhance our partnership with allied countries, particularly those that have expertise in cyber.”

King said the committee also reviewed many of the now-standard questions about how exactly to go about building a better cyber workforce within the federal government: Do cyber warriors in DoD need to meet the same physical standards as the rest of the force? How can agencies recruit and retain a quality workforce when they’re competing with the private sector?

King said DoD has had some successes in enhancing CYBERCOM’s authorities, but there’s also a need to empower the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency on the subject of recruitment and retention.

“The answer is the mission, that it’s important to people that they’re doing something important to defend the country and that the military is full of extraordinary people who could be probably making much more money in the private sector, but who are choosing the mission,” King said. “And I think that’s the same kind of mentality that we have to have in this field.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Daisy Thornton is Federal News Network’s digital managing editor. In addition to her editing responsibilities, she covers federal management, workforce and technology issues. She is also the commentary editor; email her your letters to the editor and pitches for contributed bylines.

Follow @dthorntonWFED