Exclusive

The legacy of Better Buying Power: DoD’s gambit to reform acquisition ‘from within’

The Pentagon’s internal improvement plan, known as Better Buying Power, coincided with several consecutive years of declines in the rate of cost growth for th...

This story is part one of a two-part Federal News Radio special report: Defense Acquisition at a Crossroads, exploring acquisition policy accomplishments in the last administration and challenges for the next one. Read part two of this special report.

Frank Kendall is not a fan of “acquisition reform.” By that, he mostly means the instinct that seems to be triggered on Capitol Hill every few years, when members of Congress come to believe they can remedy the Pentagon’s procurement problems with wisely crafted legislation.

Instead, during his nearly eight-year tenure — first as the deputy undersecretary of acquisition, technology and logistics and then the undersecretary — he argued the best thing would be to let the acquisition workforce work with one consistent set of policies for more than a couple years at a time so it was possible to tell what was working and what was not.

“Reform,” he argued, would have to come from within.

It turns out he may have been onto something.

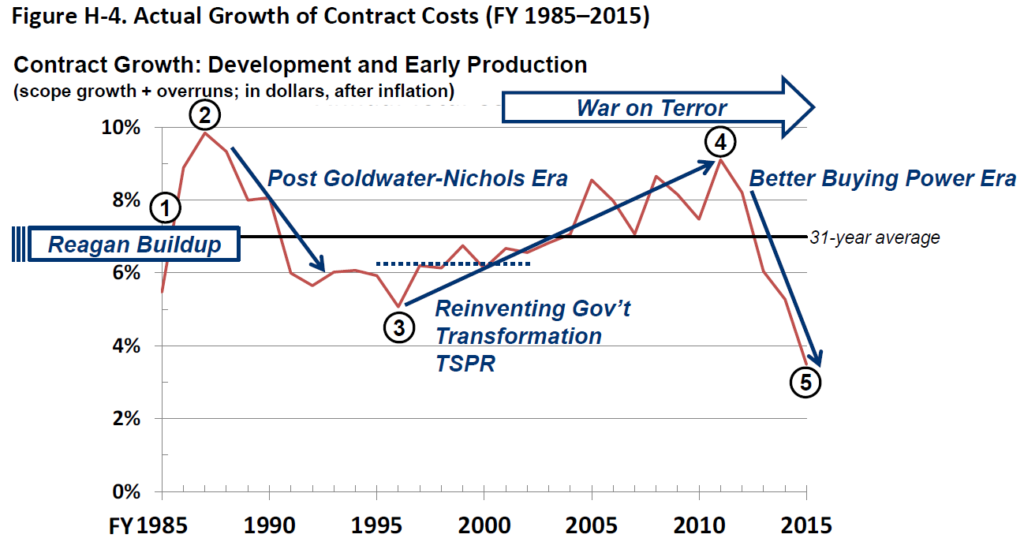

The Pentagon’s internal improvement plan, known as Better Buying Power, coincided with several consecutive years of declines in the rate of cost growth for the Pentagon’s major weapons systems, from more than 9 percent in 2011 to 3.5 percent in 2015, the lowest level since 1985. For the first time since 2000, the Pentagon in 2015 recorded no substantive breaches of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, a law that requires DoD to notify Congress when a weapons systems’ costs balloon well beyond its previously-planned baseline. By comparison, there were eight separate breaches in 2009, including seven “critical” ones.

“Cost overruns have been coming down significantly for several years. It’s an important outcome, and we shouldn’t ignore it as we think about acquisition reform,” Kendall said a few weeks ago during his final public address as undersecretary. “Given the results we’ve achieved, we should be reinforcing the things that are succeeding, not trying to take a fundamentally different direction.”

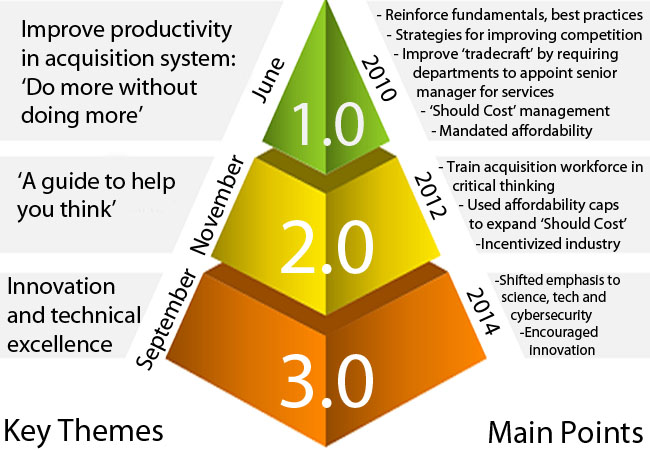

Over seven years and three separate iterations, Better Buying Power encompassed dozens of separate initiatives organized around several main themes, such as controlling costs in major weapons systems (including an insistence on not starting programs without a clear plan to make them affordable), creating incentives for industry to cut costs and deliver more innovation, boosting the training of the acquisition workforce, increasing competition and boosting DoD’s “tradecraft” in buying professional services, not just products.

The blueprint did not fix all that is wrong with Defense acquisition. Indeed, DoD weapons procurement retained its inauspicious place amid the list of a handful of “high-risk” government programs the Government Accountability Office identified in the biennial update it released on Feb. 15.

And Kendall admitted Better Buying Power didn’t do nearly enough to tackle long-term sustainment costs, which are far-and-away the most expensive aspect of any major system’s lifecycle.

But even GAO acknowledges that Better Buying Power represents exactly the sort of management attention the Defense Department must apply if it ever plans to remove itself from the high-risk list.

“I think these initiatives have helped a lot in changing the way the department is buying these big systems. As far as leadership commitment to these issues, we consider that complete,” said Michael Sullivan, GAO’s director for acquisition and sourcing management, referring to one of five criteria the office uses to determine whether a government program should graduate from its high-risk status. “That could change, of course. It could go back down because this leadership is out, we’re going to get new leaders. We’re going to have to see how the continuity works and how the agendas change, but for now, things look very good. Things have been trending in a positive light in terms of cost and schedule.”

Beginning in 2013, DoD began publishing detailed data in an aptly-named annual volume, “Performance of the Defense Acquisition System.” The department acknowledged that its own figures purporting to show positive results from Better Buying Power are drawn from extremely “noisy” data since the acquisition system is influenced by numerous factors, including year-to-year budgets and the deployment demands placed on the military.

But Andrew Hunter, the director of the Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said his think tank’s own analysis of DoD contract data largely support the conclusion that Better Buying Power succeeded in driving costs down.

“It’s pretty clear that there’s been an actual improvement that you can measure in several ways. That’s no small achievement,” said Hunter, a former House Armed Services Committee staff member who also served in the Defense Department for several years, including as Kendall’s chief of staff. “Ten years ago, when Congress told DoD to measure its performance, a lot of people considered it an impossible thing to do. But we now have measures that show us things are getting better, and I give a lot of credit for that to things like ‘should cost’ management and affordability caps.”

By “should cost,” Hunter was referring to a Better Buying Power initiative that required all of DoD’s program managers to deliver the best possible value by hunting down and eliminating cost-drivers specific to their own programs, rather than managing them according to independent Pentagon cost estimates that generally assume prior cost growth will lead to future cost growth.

The idea goes back to the first iteration of Better Buying Power in 2011, and Kendall said it had been embraced by the vast majority of DoD’s roughly 50 program executive officers.

“I still got a few that said, ‘I’m fine, I’m under my budget.’ But that’s not the definition of success,” he said. “The definition of success is you’ve set targets for yourself that will actually reduce costs and you’ve done something to achieve that. I think if there’s any one thing we’ve done in terms of cultural change, in terms of a consistent set of policies that affects outcomes, that’s it.”

Areas where Better Buying Power fell short

But in myriad other areas of the Defense acquisition system, the effects of Better Buying Power fell short of their goals — or, at least can’t be measured as easily as the development cost of major weapons systems.

David Berteau, who has been a student of acquisition reform since his tenure as the executive secretary of the Packard Commission, the Reagan-era blue ribbon panel on Defense management that laid the ground for Goldwater-Nichols Act, said principles like should-cost worked well for the systems the Pentagon already knows how to manage: tanks, bombers, nuclear-powered aircraft carriers.

“But the larger questions of how you translate that into something for the services industry, for logistics, for sustainment — that’s much tougher, and we’re further away from seeing real results in terms of knowing how you’re getting real value for money,” said Berteau, who is now the president of the Professional Services Council. “Better Buying Power never really got at the services end, the logistics end, the sustainment end. The next undersecretary is probably going to have to pick that one up.”

Indeed, services now make up the lion’s share of what the Pentagon buys. In 2016, it spent $119 billion to procure products and $156 billion on services ranging from lawn care to complex information technology integration projects.

It’s not as though Better Buying Power completely ignored services. Through the initiative, DoD ordered each of the military services to assign a senior leader to oversee all of their contracted services. Eventually, in 2016, it established “contract courts” to weed out unjustifiable contracts as part of its first-ever formal instruction on managing service acquisition. The same guidebook included provisions that categorize service procurements and set oversight roles and checkpoints according to their size — much in the same way large weapons programs are managed.

But Hunter acknowledged services did not receive as much attention as they could have during the time he served in the Pentagon and was helping to draw up the Better Buying Power guidance.

“Part of the reason for that is that the department always tends to focus more on the signals it’s getting from the media and from Congress, and the focus is almost always on the weapon systems side,” he said. “It was the same when I was on the Hill: we always told ourselves, ‘Next year’s going to be the year when we tackle services.’ We were classic procrastinators. But I do think the new DoD guidance was a substantial effort, even if it was a little late. It’s not done by any measure of the imagination and it’s going to take a lot more work, but it was a serious effort.”

Some areas difficult to measure

Hunter said there are many other aspects of Better Buying Power that may have had a positive impact but can’t yet be seen in data that can be presented on simple charts, mainly because of the long lifecycles involved in Defense procurement.

“Perhaps the latest F-35 contract is an example of that,” Hunter said, referring to President Donald Trump’s claiming of credit for having reduced the strike fighter’s per-unit price through a few conversations with Lockheed Martin executives and the F-35 program manager, seemingly ignoring multiple other factors like previously-planned larger quantities and years of difficult work by Lockheed and the acquisition workforce to reduce the program’s cost.

“I think it’s great that an incoming administration can claim credit for work that was done by their predecessors, but our research shows that when any new policy is implemented, it takes a minimum of two years to see any measurable effect,” Hunter said. “So when objectives were set to, for example, change small business goals, to reduce the number of competitions where the department only receives one bid, some of those had an impact. But it took years for the impact to really show up in the data. That’s a tough situation, because in Washington, people are looking for immediate results. That demand is hard to satisfy in the world of acquisition.”

Better Buying Power also sought to make changes in DoD’s acquisition workforce, and the results from those initiatives are not only lagging indicators, it’s probably impossible to plot their results on a chart or in a report to Congress.

DoD framed the initiative’s second iteration, in 2012, around the acquisition workforce as “a guide to help you think.” Kendall’s wanted to send the message that no two programs are alike and that the department’s acquisition professionals should use their skills and training to tailor their strategies within the Better Buying Power program’s principles, as long as they have the technical skills to understand the program they’re trying to build. Kendall emphasized at the time that he wanted to avoid the mistakes of previous acquisition leaders who indicated a blanket preference for, for example, fixed-price contracts.

“I don’t start with the DoD instruction on acquisition and a specific set of milestones that I then have to fit my program into, I start the other way around,” Kendall said. “I start with the product. What’s the most efficient way to develop this product? Every one is unique in terms of the complexity, the urgency, the amount of risk the government is willing to take.”

Kendall re-wrote DoD instruction 5000.02, DoD’s main guidebook for acquisition in 2015. It offered several possible templates for structuring a potential program depending on what sort of product the department was buying, but emphasized that managers would need to tailor it to their needs.

Stacy Cummings, the program executive officer for Defense health management systems, said that philosophy turned out to be pivotal to the main project in her portfolio, MHS Genesis, the $4.3 billion commercial-off-the-shelf replacement for DoD’s aging electronic health record systems.

DoD awarded the contract for the system in July 2015, and it went live at its first site, Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington earlier this month, a rapid turnaround that probably could not have been achieved without top-cover and encouragement from senior Defense management to combine the acquisition authorities the department already has in more creative ways.

“Our program is very tailored,” she said. “There are certain DoD acquisition processes we were able to leverage to tailor this program in a way that let us do a lot of things concurrently, as opposed to a traditional acquisition program where you’d have to do a lot of things in serial. It allowed us to implement this quicker, to get it out to the users quicker, and we’re going to learn so much more by putting it out in a military treatment facility than if we didn’t have that firsthand experience. That’s the best thing that’s come out of our implementation of Better Buying Power.”

Cummings is a career DoD acquisition professional who took a brief hiatus from DoD to work at the Department of Transportation in 2011 — about the time Better Buying Power started — and returned to lead the electronic health record project in 2016, after the initiative was well into the third iteration, which focused on technological superiority.

She said one takeaway from that before-and-after experience was that DoD has recognized that acquisition is a team sport that doesn’t only include government positions that are traditionally coded or thought of as members of the acquisition workforce.

“There’s always been a focus on making sure our workforce is certified and trained, but I think there’s a recognition that there’s a broader group of people in a program office that need to work together as part of an integrated team if you’re going to successfully deploy a program,” she said. “And the openness to encourage tailoring based on the needs of the program, good decision making, getting our requirements right, the focus on affordability — I think all of that messaging was coming through much more loud and clear from AT&L than I recall from my past.”

From its inception, DoD intended Better Buying Power’s audience to primarily be the department’s own acquisition workforce. But Defense officials also emphasized from the beginning that they wanted input from industry, particularly in the areas that most impacted defense contractors, such as the initiative’s focus on reducing the particular bits of bureaucracy that add to cost and schedule without producing any meaningful value.

Defense vendors at first welcomed what seemed like might have been a unique opportunity to help influence acquisition policy. But they quickly realized that the department’s request for input was far from a guarantee that their concerns about the acquisition process would be addressed as part of Better Buying Power.

A prime example is an alleged overuse of contract competitions that DoD awards on a lowest-price technically acceptable (LPTA) basis.

Within the Defense industry, the common view is that the first version of Better Buying Power’s emphasis on lowering costs led the acquisition workforce to interpret the guidance as a preference for LPTA contracts whenever possible. Although DoD has largely denied that the problem exists, defense vendors and trade associations say it persists to this day.

“Their subsequent attempts to modify or make clear what they really meant still haven’t turned that ship around, and many, many contracting officers within DoD still use LPTA as their default method for selecting solutions,” said David Drabkin, a former deputy chief acquisition officer at the General Services Administration, who now runs a private consulting firm. “That’s not to say that the government shouldn’t try to negotiate the best price it can get, but the government should want to get value. [LPTA] denies the department the opportunity to take advantage of the values that a slightly more expensive but more technically advanced solution might deliver. In today’s environment, there’s no telling what something that you buy today might be adapted to in the future, and in today’s marketplace, no commercial company wants to get into a bidding war just to do business with the government despite the fact that they might have an excellent product.”

Hunter said DoD was well aware of industry concerns like LPTA and other complaints such as the thresholds at which companies would have to submit certified cost and pricing data throughout the Better Buying Power policy development process.

At various intervals, Kendall tried to address them, including through a March 2015 policy memo in which he admonished contracting officers that LPTA contracts are a poor choice when the government is asking industry to deliver innovative products or services.

“Industry was not always satisfied about how much of their input was taken into consideration. I think that changed in the later iterations of Better Buying Power, but it’s a fair critique,” he said. “But it bears mentioning that LPTA was not ever a Better Buying Power initiative. It’s not something the department’s leadership was pushing. You won’t find it in any of the guidance, it was never there. The tricky part is that nobody quite agrees on what an LPTA-type solicitation is. The department didn’t want to fall into the trap of telling people, ‘Never use LPTA,’ and then ending up with a bunch of competitions where best value was winning where there really wasn’t a significant difference between the competitors. That can give you a lot of trouble in the bid protest world.”

Also, despite Kendall’s repeated and consistent insistence that competition was the single best tool at the Defense Department’s disposal to drive costs down and achieve better results, the results from Better Buying Power are, at best, mixed on that front. He deserves credit for collecting and publishing data on how Defense components have been doing in fostering more competition in their contracts, but the latest results showed that by some metrics, DoD is getting worse, not better: in 2016, less than half of the department’s contract spending went into meaningful competitions where there were two or more bidders.

Whatever deficiencies from which Better Buying Power suffered, many of its attributes are certainly worth carrying forward into the new administration, GAO’s Sullivan said.

“The stuff that they’ve done that helps to create a better business case at the outset of a program are the things that we think have really made a change in the investments they’re making,” he said. “But also, in our ‘quick look’ reports every year, we always look at how they’re doing with should-cost, and they’ve been able to capture $21 billion in savings. I think it’s been a positive thing.”

That said, any internal acquisition improvement initiatives that endure into the tenure of Kendall’s successor will almost be certainly called something different.

“The history of changes in administration is that everything has to look new,” Berteau said. “You don’t pick up names and nomenclature from the prior administration, but the initiatives will probably maintain themselves. The idea of performance-based logistics, for instance — if the government can define the performance it’s trying to achieve and then figure out what the right value of that is and produce better outcomes for less cost over time – that’s an objective that I think will survive well into the next administration.”

Speaking at a conference in San Diego last week, Kendall put his hopes for the future of acquisition rather succinctly.

“At the end of the day, it’s about professionalism,” he said. “You have to have incentives for professionals in government and industry to do the right thing, and you need to have close cooperation with the operators to make sure their requirements are reasonable. It’s not that hard an equation. But the variety of circumstances we deal with is almost infinite. You’ve gotta give people a chance to do their jobs, do them well, and then hold them accountable for that.”

On Wednesday, in part two of Federal News Radio’s special report: Defense Acquisition at a Crossroads, we’ll explore challenges facing the next administration, including the new Congressional mandate to split DoD’s acquisition bureaucracy into two separate offices. Read part two of this special report.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED

Related Stories