Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

On Air: Federal News Network

Trending:

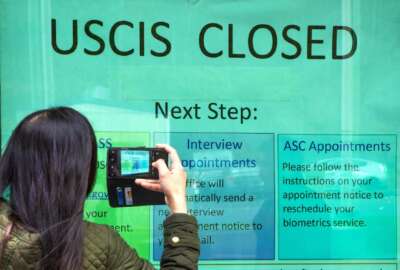

USCIS sets ambitious hiring, processing goals to shrink massive immigration case backlog

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ backlog has nearly 5.2 million cases and approximately 8.5 million cases are pending, according the agency's Ombuds...

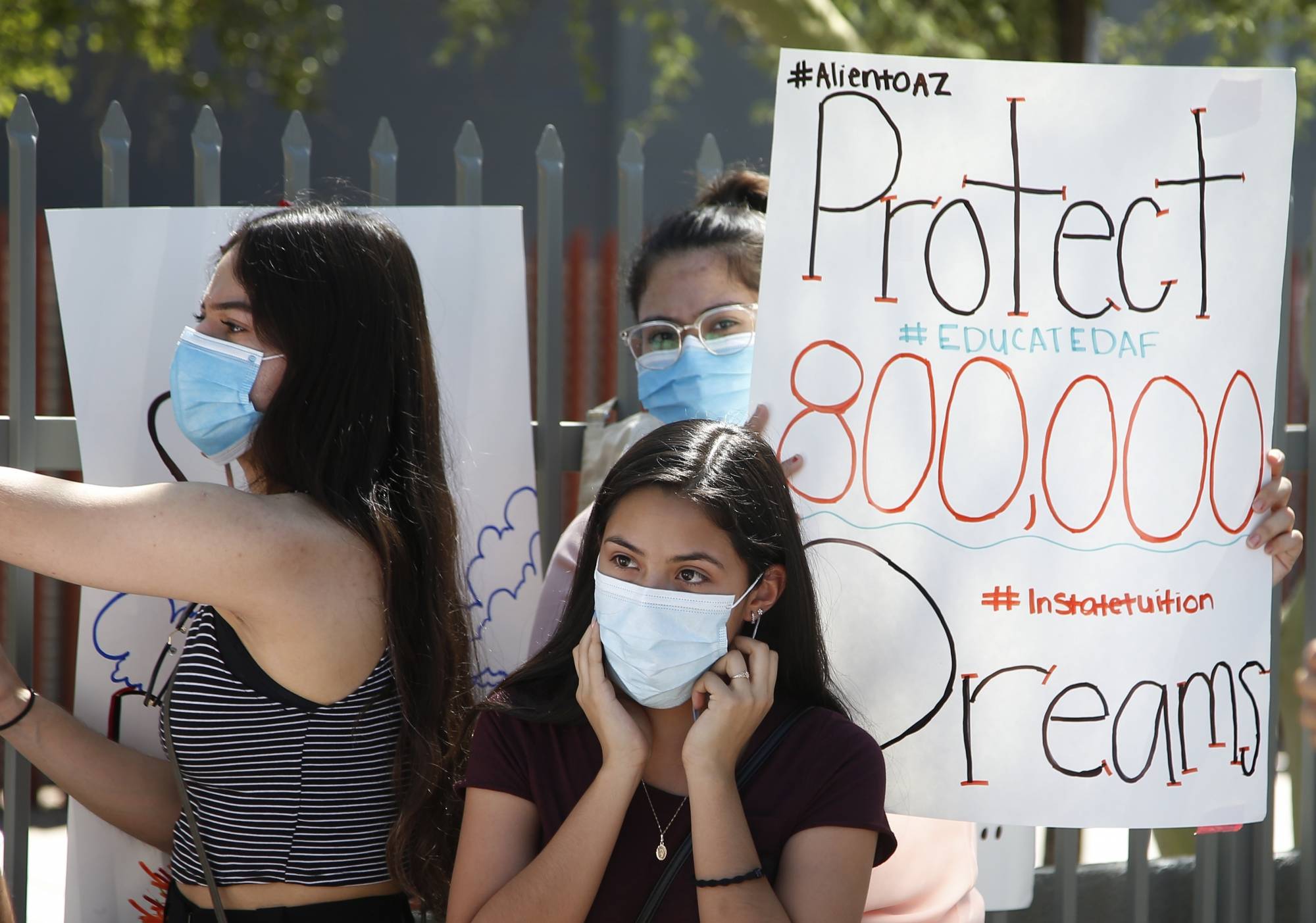

The public’s liaison to the Department of Homeland Security’s lead immigration agency has one primary focus in this year’s annual report to Congress: reducing the backlog of cases and its impacts. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ backlog has nearly 5.2 million cases and approximately 8.5 million cases are pending, according the CIS Ombudsman Phyllis Coven.

By comparison, the backlog was around 2.7 million in July 2019. On a call with USCIS leadership Wednesday, Coven said the affirmative asylum backlog is worst of all.

“We’re hyper focused on all backlogs, but there are some impacts beyond just the time loss. That’s of great concern to us. We’re examining things like how customers can request, expedite and advance parole, which snowball because of the backlogs,” Coven said. “We looked at needed solutions, including digital ones to encourage the agency to take bolder steps. And we’re also trying to give due credit where it’s due such as the approach of dealing with the U visa [for nonimmigrant victims of certain crimes] backlog that the agency has undertaken by developing the [Bona Fide Determination] process.”

USCIS struggles to hire enough staff to address the case backlog, even after hiring freezes in fiscal 2019 and 2020 lifted. In fiscal 2020, the average time to onboard a new adjudicator was 97 to 118 days after the date of a hiring decision, according to the CIS Obudsman’s office.

Dan Renaud, senior counselor to the USCIS director, said that when social distancing measures were in place, staff used video interviews and biometrics to continue processing cases. He also said the agency leveraged appropriations to cover overtime for adjudicators.

“Our first round of hiring has favored more towards supervisory roles, which has meant additional internal promotions and an HR infrastructure that’s ready to support an increase in new staff. We’re glad that we’ve been able to promote those career civil servants committed to our mission,” he said.

USCIS plans to hire more than 4,000 employees by the end of this calendar year, and set new, more aggressive “cycle time” goals for fiscal 2023. Renaud said these are an internal management metric comparable to median processing time.

Timesaving accommodations were made for certain applicants. Doug Rand, senior advisor to the USCIS director, said individuals in the health care and child care industries who are renewing their work authorizations can request an expedited review and completion of their employment authorization document renewals. The work permit validity period also increased from one to two years for certain “adjustment of status” and humanitarian applicants.

Meanwhile, back in March, USCIS published a final rule to effectively expand premium processing services for cases, which is an additional fee applicants can pay to expedite their forms. But this expedited service is still handled by human beings, and Rand said there is a limit to how many cases employees can process at once.

“One needs extra human beings to be able to do a faster turnaround time. So we understand and appreciate the fact that a lot of folks out there would be paying for premium processing for a lot of these ones right now, if they could,” Rand said. “We really want to satisfy that demand. We wish we could, we could just flip a switch and turn it on for everybody, but that’s not really operationally possible.”

Fee-for-service model leaves USCIS underfunded, understaffed

Although the CIS Ombudsman’s annual report to Congress is due by June 30, Coven’s office already issued two formal recommendations on March 31 and June 15. One was to amending USCIS’ funding model which relies almost entirely on fees-for-service, a long-running obstacle for the agency to tackle its backlog.

USCIS’ workforce of more than 20,000 people and 200-plus offices and facilities have an annual budget averaging above $4 billion since 2018, 97% of which comes from fees-for-service. The federal review and public comment process for adjusting fees takes several years, and the agency has never adjusted those fees for inflation – which reached an annual rate of 8.6% in May, the highest in 41 years.

But that’s not all.

The drop in services performed by USCIS during the pandemic, various humanitarian disasters that occur at unforeseen times, and cuts to nonpayroll expenses in order to avoid a massive COVID-related furlough compounded to reveal the inadequacy of USCIS’ funding model, the ombudsman wrote. The recommendations included dedicated appropriations to tackle case backlogs, and to cover humanitarian and asylum services which are not fee-based yet paid for at the expense of applicants for other immigration needs.

“We recommend that USCIS seek legislative or regulatory action to: Reengineer the agency’s biennial fee review process, particularly its associated staffing allocation models, to ensure it fully and proactively projects the staffing levels needed to meet targeted processing time goals for future processing as well as backlog adjudications … [and] Authorize and establish a financing mechanism, through the auspices of the Department of the Treasury, that USCIS may draw upon to address unexpected revenue shortfalls and unfunded policy shifts and to maintain adequate staffing to meet its performance obligations to its customers and Congress,” the report said.

Although, researchers pointed out in 2020, when USCIS requested emergency funding, “As a fee-funded agency, USCIS has been largely exempt from customary congressional oversight,” and the reason it was made a self-standing agency was to “strengthen the benefit-granting functions of the immigration system and sever them from [congressional] enforcement missions.”

‘Efficiency at the expense of equity’

The second recommendation was to improve the notification process for Form I-129 beneficiaries. Form I-129 is a petition filed by an employer to extend, amend or change the status of their nonimmigrant worker. Currently, USCIS only notifies employers of actions and status changes for the application, but does not notify the workers who would in fact benefit from the I-129 petition. According to the CIS Ombudsman, this means those workers reply on their employers for all information, which could leave them without status documentation and make them susceptible to abuse. The report called this “administrative efficiency at the expense of equity,” echoing several of the Biden administration’s directives for improving customer experience and the federal workforce as a whole.

As of now, eligible nonimmigrant workers are supposed to receive a tear-off Form I-94 from their employer, which they carry around at all times. Employers keep a copy, but USCIS will not send the form to workers themselves.

Proposed solutions included notifying beneficiaries by mail or online; allowing beneficiaries to track their status online; and for USCIS to collaborate with Customs and Border Protection so that applicants can check their Form I-94 status online using passport information.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Amelia Brust

Amelia Brust is a digital editor at Federal News Network.

Follow @abrustWFED

Related Stories

Related Stories

-

USCIS looking to hire thousands to help speed up asylum process Federal Newscast