Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Hubbard Radio Washington DC, LLC. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Burdened by student debt, the youngest federal employees are entering the workforce later than their predecessors. As part of a Federal News Radio special repor...

Like many federal employees her age, Abygail Mangar, a 24-year-old engineer, has a passion for public service. She learned from her mom, a former Defense employee herself, that she could have a long, stable career in government.

But Mangar wants to return to school to earn a master’s degree, and after nearly three years at the Transportation Department, she will leave the agency in July.

When she heard she may have the opportunity to take advantage of a DoT program that would help her pay for school, Mangar told her supervisors she was interested. But the program only is available to permanent employees, and Mangar isn’t one.

And when she heard DoT planned to extend her term appointment for another two years, Mangar began looking for other options. She recently accepted a position with AmeriCorps, which will help pay for graduate school once she finishes her term.

“I’m told a lot about retirement, and retirement is definitely something that’s important, but I have things I need to pay for now,” Mangar said. “Being able to have a pay jump from doing a degree to being able to pay for loans is a big thing for me. Having loan forgiveness is a big thing. The major concerns of someone who’s a boomer are not the same thing as someone who’s a millennial, and I don’t think the older generation understands that.”

Mangar isn’t alone. As part of Federal News Radio’s Special Report, What millennials really want from federal service, many “millennials” in government said their agencies haven’t yet understood what makes them tick. And their generation isn’t drastically different than the ones that have come before it.

Yet many agencies — and the federal personnel system itself — are not ready to support how the next generation of young government employees is different than its predecessors.

“They’re much more burdened with student debt than other generations were, and that affects a lot of their choices,” said Peter Viechnicki, a strategic analysis manager and data scientist with Deloitte. “They typically enter the labor market later, so they start working in government later than people in Generation X or the Baby Boom generation did. When they do, they have this debt and that affects the financial choices they make and may affect other choices they make during their careers.”

A Federal News Radio survey of more than 900 current and former federal employees and managers and members of Young Government Leaders found that most millennials, or employees under the age of 35, have a passion for public service and would prefer to stay in government — as long as they have opportunities to develop their skills, careers and benefits.

Many millennials in the survey indicated that programs such as student loan repayment are attractive to them, if their agencies have the funding to support it. Thirty-three agencies handed out $58.7 million in loan benefits in fiscal 2014 — 11 percent more than the $52.9 million in payments 31 agencies made in 2013, according to the Office of Personnel Management’s most recent report to Congress.

But funding for these programs has steadily dropped in recent years, though spending did rebound slightly in 2014 after the previous year’s annual low of $52.9 million.

“Sure, Uncle Sam pays lip service to recruiting young employees,” wrote one survey respondent who is in his early 30s. “But when push comes to shove, the money’s not there for student loan repayment or employee training. And recruiting talented college grads to do administrative work for the first five years of their career is a recipe for high attrition rates.”

A 2015 Partnership for Public Service study of Office of Personnel Management data painted a grim picture of the future federal workforce.

From 2010 to 2015, the percentage of federal employees under the age of 30 dropped from 9.1 percent to 6.6. percent. While the percentage of feds under age 25 declined from 2 percent to 0.92 percent.

But the picture behind those numbers is more complicated.

Hiring in the federal workforce dropped steadily from 2011 to 2013, with Executive Branch agency new hires falling from 108,464 to 76,932 over those two years.

New statistics from OPM show that hiring picked up in 2014 and again in 2015. Executive Branch agencies hired 122,228 new employees last year.

Though agencies made slightly better progress in 2015 hiring a larger proportion of new federal employees under age 35, older workers are not yet retiring in vast numbers like OPM originally predicted.

“When the economy is bad, people just hold onto to their jobs and that’s one of the things that’s motivating a lot of the older workers in federal and state governments to just kind of stay put and keep going for another year or two, just waiting to see what the economy is going to do,” Deloitte’s Viechnicki said.

And the millennials who are in the federal workforce aren’t jumping ship for the private sector any more quickly than workers in previous generations.

According to Federal News Radio’s survey, the majority of federal employees under age 35 — 61 percent — said they did not anticipate leaving government, though many indicated that their decision to leave or stay would depend on the possibility for promotion or changes to their pay and benefits.

“Job stability and job satisfaction are key,” one respondent wrote. “I want to do good work, work for and with good people and then go home at the end of the day. Federal service currently provides all of this.”

By the end of 2011, Executive Branch agencies hired 107,809 new full time, permanent employees under the age of 30, OPM said. Roughly 82,026 of those employees, or 76 percent, remain in the federal workforce as of September 2015, OPM said.

“Based on a review of the last five years, employees under 30 are not separating from the federal government at any higher rate than other age cohorts,” an OPM spokesperson told Federal News Radio.

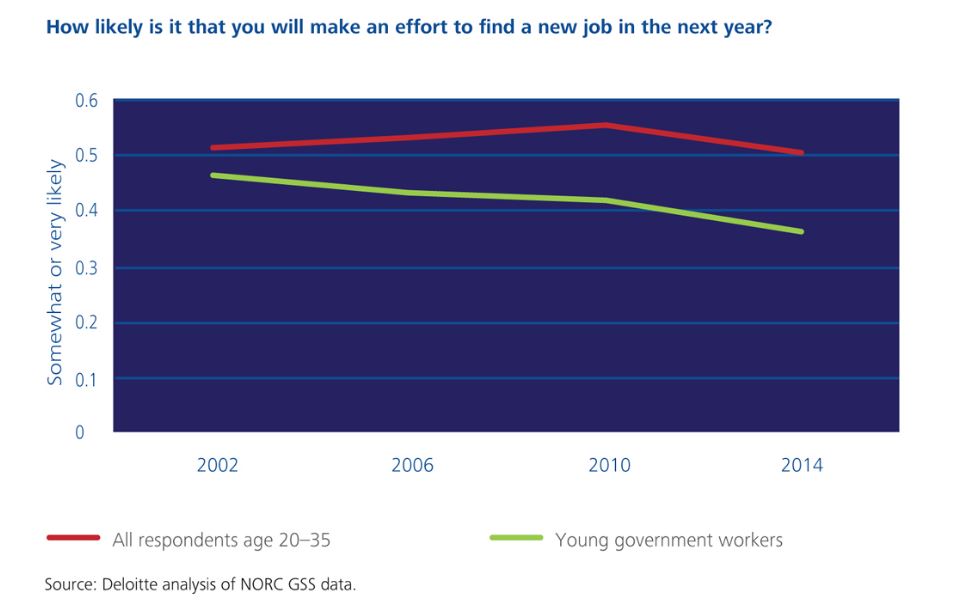

A November 2015 report from Deloitte found that millennial government employees were less likely to look for a new job in the next year than their counterparts in the private sector or their predecessors in Generation X. Roughly 36 percent of millennial employees in government intend to look for another job, compared with 51 percent of all millennials in the workforce, Deloitte found.  For millennials who do anticipate leaving the federal government, the majority — 45.6 percent — told Federal News Radio that they plan to leave within one to three years. Few opportunities for promotion and changes to their pay, benefits and retirement were the most important factors that would contribute to their decision to leave government.

For millennials who do anticipate leaving the federal government, the majority — 45.6 percent — told Federal News Radio that they plan to leave within one to three years. Few opportunities for promotion and changes to their pay, benefits and retirement were the most important factors that would contribute to their decision to leave government.

Millennials are also overwhelmingly positive about the potential they see for themselves in government. About 80 percent of Federal News Radio respondents said they see a future for themselves in government, while 57.5 percent said they envisioned future careers for themselves at their current agencies. Roughly 75.6 percent of millennial respondents said they had opportunities to develop their skills and career in the federal government.

Statistics show millennials generally are not any less engaged or satisfied with their jobs in the federal workplace than any other generation.

Employee engagement has declined overall within the federal workforce over the past six years. But the reasons for that drop — tight budgets, pay freezes, government shutdowns and a more volatile political discourse — are not specific to the younger generation over another.

“All that has had an effect on general morale for all federal employees, and that’s certainly what we see,” Viechnicki said. “When we looked at the specific numbers for millennials, their morale and their engagement wasn’t worse than any other generation in federal service.”

But what keeps millennials engaged may differ from the motivations that drive an older generation of federal employees.

“The idea of working 30-plus years for a pension, which I’ve paid a substantial amount into, does not motivate me,” one survey respondent wrote. “At the end of my career, I don’t want to feel like my biggest legacy is a cleaned-out cubicle.”

Many young federal workers said they were frustrated by a sense of complacency among their older colleagues.

Stefanie, a former federal employee at the Environmental Protection Agency in her mid-20s who requested partial anonymity to speak more candidly about her experience, left her fellowship program after a year. She now works for a non-profit.

While she said she learned a lot from her EPA mentors and gained plenty of valuable experience, the year she spent in federal government taught her that she didn’t feel strongly about staying. She expected that her colleagues would approach their work with more passion — not a sense of “this is the way we’ve always done it.”

“I really got a very big sense of complacency among some people,” Stefanie said. “They had this nice job with great benefits, a great salary, and maybe once they were impassioned. But it didn’t really seem like they were anymore.”

That sense of complacency isn’t necessarily unique to one age group over another, said Christina Lee, one of the lead researchers who contributed to a Society for Human Resource Management study on the millennial generation.

“Millennials, when compared to other generations, we found that they’re pretty similar, maybe a slightly different mindset,” she said. “We did find that millennials are really focused on having a purpose and wanting to participate in meaningful projects.”

For Viechnicki, federal managers should welcome different mindsets and acknowledge that their employees are at different life stages as well. They should identify development opportunities for their employees not based on age, but rather their place in life.

“This generation isn’t much different than previous ones,” another respondent in his early 30s wrote. “In 10 years, we’ll prioritize family. In 20 years, we’ll worry about saving for retirement. And in 30-40 years, we’ll complain about the new generation entering the workforce, while stymieing their career paths by never retiring.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED