Exclusive

OPM employees voiceless as administration ramped up merger efforts

Federal News Network conducted a six-month investigation exploring how the administration’s proposed merger of GSA and OPM left employees with more questions ...

Editor’s note: This is part 2 of a two-part special investigation by Federal News Network about the lasting impact the potential merger of the Office of Personnel Management and the General Services Administration is having on OPM’s employees and missions. In part 1, we explore the impact of the merger planning on employees, their work and the organization as a whole.

The Trump administration wasn’t the first to consider merging or restructuring the Office of Personnel Management.

The George W. Bush and Obama administration contemplated reducing OPM’s reach or even doing away with it altogether. In drafting legislation to establish the Civil Service Commission as OPM, the Carter administration even considered placing the agency within the Executive Office of the President but ultimately decided against it.

Prior administrations never seriously moved forward with these plans, in part, because of the sheer complexity and magnitude of OPM’s involvement across much of government.

Untangling those complexities even with a detailed plan would be difficult. Without one, the task would seem unimaginable.

Nearly a year after the Trump administration first revealed its proposal to merge much of OPM with the General Services Administration, current and former employees, and lawmakers, say they haven’t seen a detailed plan for the agency’s reorganization.

The workforce has received mixed messages about the future of their agency and their jobs from Congress, which has been relatively consistent in opposing the merger, and Margaret Weichert, the deputy director for management at the Office of Management and Budget who led OPM on an acting basis for nearly a year.

Weichert, according to OPM and government sources, has said the administration would “play chicken with Congress” if lawmakers didn’t agree to move forward with the merger proposal.

Over the last six months, Federal News Network spoke with 10 current and former OPM employees, all of whom requested anonymity to speak candidly about the merger. They described how the past year of uncertainty surrounding the OPM-GSA merger has delayed work, lowered morale and driven institutional talent to leave.

And many current and former OPM employees said they’ve become skeptical of acting leadership and the motives behind the administration’s proposed merger — even as many acknowledge the agency has room to improve and could become more efficient.

“It’s not that people are necessarily against this change or against consolidating certain parts of the agency, but people are against being stupid about it,” a government source with knowledge of OPM said. “I’m against the forced sterilization of the agency just to force a political opinion.”

Related Stories

Congress not yet convinced of Trump administration’s proposed OPM-GSA merger

The agency, of course, is no stranger to acting leadership.

Beth Cobert, who also served concurrently as OMB deputy director for management and acting OPM director, led the agency for more than a year-and-a-half during the Obama administration. The Senate never confirmed her to the permanent position.

But current and former OPM employees said it was different then.

“I absolutely felt like I had voice then. Those were directors [who] had a voice at the agency, a vested interest in making sure OPM did well,” a former employee said.

All of that hope started to dissipate, especially as Congress, despite OPM’s own warnings, transferred the bulk of the National Background Investigations Bureau’s security clearance business to the Pentagon.

As Federal News Network first reported in November 2017, OPM, which relies on the fees it collects performing background investigations to fund much of its operations, said it could lose anywhere from $74 million-to-$112 million in revenue through the move.

But few paid attention to the impending budget shortfall. And Congress, with little to no public debate on the matter, sent much of the NBIB security clearance program back to the Pentagon, the same agency that first tossed the business to OPM in 2005 when its own investigative backlog grew too big to handle.

At the time, it seemed like no one cared.

“There wasn’t a strong voice, no politically-appointed person at the table to defend OPM,” a former employee said.

OPM employees sought more details about the merger

As Weichert took the reins at OPM last October, she said she planned to meet with employees and hear out their concerns. Today, she maintains she spent a significant amount of time talking to the workforce about the merger.

“I absolutely had all the time in the world for the people who were hurting and concerned,” she said in an interview with Federal News Network. “I didn’t sugarcoat anything. We are in a situation of change, and it’s not a situation created by this administration.”

Weichert said she asked the agency’s program leaders to inform her of employees who appeared particularly anxious or worried.

“I spent a lot of time one-on-one with SES down to people in the mail room to hear them and understand those concerns — and as much as possible address them,” she said.

While employees said they were appreciative of the opportunity to speak with Weichert, the meetings usually didn’t end with meaningful information and seemed like more of an “exercise” instead of a chance to be “transparent.”

“As employees, we would hear the same thing over and over again,” one former OPM employee said. “There wouldn’t be specific details about how they would move specific people around. That caused a lot of anxiety.”

Latest Workforce News

The former employee said employees posed these concerns to OPM leadership, but the agency never seemed to pursue those options.

“I didn’t speak with anyone who said they knew what was going on, [or who thought they] had enough information [or] were satisfied with the information,” an OPM employee said.

Another OPM employee said Weichert recognized during her final town hall with the agency that her perspective about the agency, its mission and its people has changed.

“Margaret told the town hall what a learning experience it had been for her over the last year,” the employee said. “She said she has a very positive view of the agency now.”

Looking back, Weichert acknowledged she could have pitched the OPM-GSA merger differently.

“I’ve learned a lot about communication,” she said. “To be totally clear, I did not get out in front of Congress. I’ve been talking to Congress about this since the get-go. I have reached out to Congress. I’ve reached out on a bipartisan, bicameral basis. It has been useful, apparently, to some individuals to imply that I have not been working with Congress. I have been doing everything I can to work with Congress. I would argue Congress has not been genuine in their willingness to work with me.”

Weichert said she and her team reviewed recommendations from the Government Accountability Office and other good-government groups, which she saw as a valuable justification for the OPM-GSA merger.

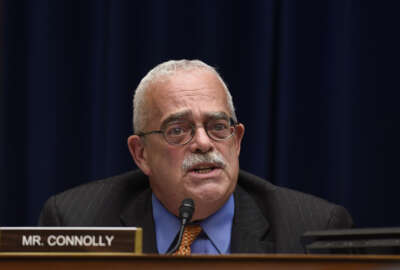

Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), chairman of the Oversight and Reform Government Operations Subcommittee who led a request for a wide variety of information about OMB’s merger proposal, flatly disagreed.

“We’re at an impasse,” he said of the subcommittee’s request for more information. “The only data they provided was stuff we already had or that frankly was unresponsive to the request. I met with Ms. Weichert. They have obviously decided to stonewall and be unresponsive.”

That impasse, as well as the continued departures of long-time executives from the agency, is leaving OPM in a precarious spot.

A break in the clouds?

As the new fiscal year begins, there is some hope the dark days at OPM are in the rearview mirror. Perhaps the clouds that have been engulfing the agency over the last 18 months will break, employees said.

The agency, at last, has permanent leadership in Dale Cabaniss, a former chairwoman of the Federal Labor Relations Authority and Senate appropriations staff member. The Senate confirmed her Sept. 11 after Trump nominated her in March.

Though some are cautious about Cabaniss — federal employee unions and Democratic senators have pointed to low employee engagement scores at FLRA during her tenure — she comes into the role with more knowledge about OPM than many previous directors and, maybe more importantly, she understands how Congress and the executive branch need to work together.

Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.), the ranking member of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, has made his skepticism known about the new director.

“The director of OPM plays a crucial role in the federal government — not only by managing the agency’s employees — but by serving as a leader and advocate for the more than 2 million hardworking men and women in the federal workforce,” he said in a September speech from the Senate floor opposing Cabaniss’ nomination.

It still is unclear whether Cabaniss will carry the administration’s merger torch or focus on her own priorities in the potentially short amount of time she has as the director — or whether OMB will continue to lead quietly from the corner.

“At least we have someone in the building five days a week right now,” an employee said. “But there’s sort of a sense of waiting for direction. Welcome aboard and also what’s the plan?”

OPM employees and those familiar with the agency say discussions are ongoing to advance more pieces of the GSA merger. The two agencies, for example, are actively discussing whether GSA can take over the management of OPM’s buildings, at least three sources have said.

One source said Weichert, during her last town hall, tried to put the workforce at ease about GSA managing the agency’s buildings. GSA already owns the building in downtown Washington, and facility management is a larger part of its core mission than OPM’s, a source said.

“I’m going to actively oppose any attempt to implement any part of this, until and unless they set the reset button and act like responsive officers of the republic in respecting the legislative branch and engaging with it, and then we can talk,” Connolly said. “If there’s a compelling rationale for changes, we’re open to them, but not this way.”

An aide for Peters said the ranking member would carefully monitor the situation at OPM as the agency transitions to new leadership.

At the same time, OPM does have more appropriated funding, which Weichert and OMB pushed Congress to include in the short-term continuing resolution members passed last week.

Congress included a $48 million budget anomaly and granted OPM the authority to transfer nearly $30 million from the trust funds it manages to supplement agency operations. This extra funding is necessary, Weichert has argued, to keep OPM afloat once the security clearance business moves to DoD.

“We are actually working with a number of members and there is evidence that Congress is understanding things since the budget agreement,” Weichert said. “Congress understood, particularly on Senate side, that we need GSA’s help to right the ship.”

“We are very confident that Congress does understand the challenges the NBIB departure will have on OPM around funding,” she added.

For Connolly, the OPM-GSA merger is dead in the water. The House included specific language and amendments in appropriations and the annual defense authorization bills to block any part of the administration’s proposal.

“What comes next is the status-quo ante,” he said. “You don’t get to do this. OPM will be protected. It’s up and running. It has a mission, and if you want to change any aspect of that, you come to Congress and the committees of jurisdiction and we’d be glad to sit down and talk about the ideas you may have, and we’ll share our ideas as well.”

Weichert, however, said she considers that language part of the “poison pill” riders that congressional leaders agreed wouldn’t be part of the coming budget negotiations.

“I do believe people are starting to understand the nature of the clear and present dangers OPM is facing, and the opportunity to do an integrated management capability that centralizes lot of activities around shared services,” she said.

Meanwhile, the OPM workforce is in suspense — and is looking for some kind of direction.

“So if Congress is going to say ‘no, we’re not doing this,’ when is someone going to give this a time of death?” one OPM employee said. “When are we getting back to normal?”

Editor’s note: This is part 2 of a two-part special investigation by Federal News Network about the lasting impact the potential merger of the Office of Personnel Management and the General Services Administration is having on OPM’s employees and missions. In part 1, we explore the impact of the merger planning on employees, their work and the organization as a whole.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED